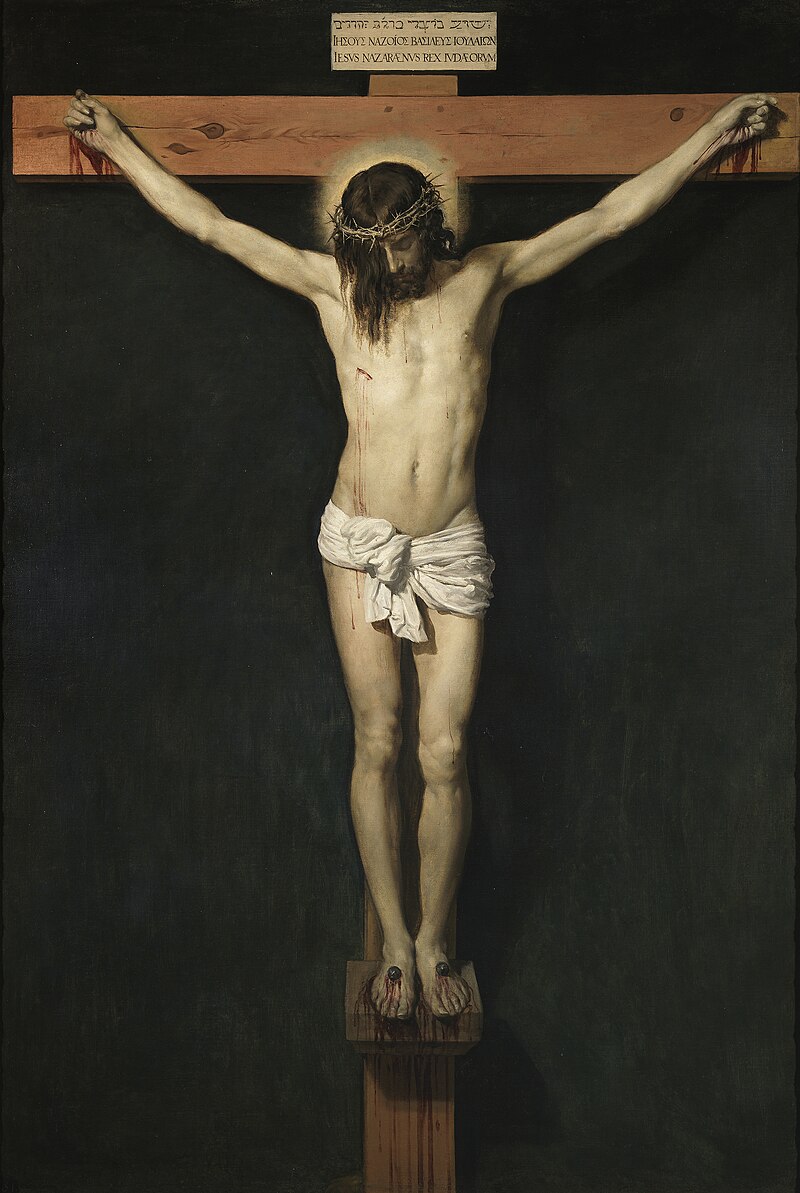

Christ Crucified, Diego Velázquez, 1632

Near the heart of the city of Madrid, its white columns glimmering in the rays of El Sol, stands the Museo Del Prado. Built in 1785 under the orders of King Charles III, it was originally intended to be the home of the National History Cabinet. Luckily for us, however, and thanks to the prompting of his wife, King Ferdinand VII (the grandson of King Charles) designated it as the Royal Museum of Paintings and Sculptures and now is the home of some of the most significant and beautiful works of art in the world.

One such work, watching over the paintings in room 014, is Christ Crucified, painted by Diego Velázquez around 1632. It depicts Christ suspended on the cross, his pale figure illuminated against the darkness of the background, his isolation in his passion driven into our minds by the starkness and loneliness of his setting. By the wound on his side, we know that he’s already dead, but despite the gruesome details of the story of his death, this Christ is peaceful. He’s upright and firm, his face is calm and beautiful. Contrary to the more popular trend of the time of placing one foot atop the other, he’s instead held up by two feet planted on the suppedaneum, giving us a sense of rest, of stability, and of firmness. The Christ in this work is beautiful and calm- Velázquez is showing us a different aspect of this scene, drawing from the idea that Christ, while being beautiful in his soul, was also the most physically beautiful person to live. This isn’t the dramatic, emotional and gruesome crucifixions we’re used to seeing from the baroque. This Christ seems to be gently reposing on the cross, beautiful, serene, and solemn. His face is partially veiled by a curtain of his hair, drawing us in and inviting us to look closer to peak under and reveal the beauty of his face.

The entire painting, its solitary setting, its calmness and serenity, the four nails, the already dead Christ- everything even down to the fully written text above Christ’s head (“Jesus of Nazareth, king of the Jews” In Latin, Hebrew, and Greek), is a massive departure from the baroque trends of the time. They favored three nails, a living, suffering figure with a more dynamic, twisting pose, an abbreviated INRI instead of the written text, and most significantly, the drama and emotion of the typical Baroque crucifixion.

All these aspects that Velázquez is rejecting and the solemnity of the iconographic quality he’s embracing come from the ideas of the artist Pacheco, who advocated for these breaks in the trends in his book Art of Painting. His idea was to create something that was ancient, that pulled from the old iconographic ideas of painting, that inspired the viewer with its solemnity. Pacheco believed that painting was the superior medium, it could, he said, create something embraceable. Paintings such as this were made for chapels and churches, to be hung among the softly glowing candles and gazed upon during prayer. Pacheco wanted artists to create an experience– the solemnity of feeling as though the figure was incarnate in front of you, and if you reached out, you could embrace it.

These ideas are more than evident in Velázquez’ Christ- He took these ideas and transcended them into something above and beyond anything attempted before. His Christ is so soft and lifelike, so delicate and beautiful, it feels as though you have to hold your breath or you might disturb the sweet rest of the gentle figure. Unlike any painting of its time, Velázquez shows us a Christ that is gently reposing on the perfectly crafted cross, enveloped in softness and light, stretching out his arms on the beams of the cross, inviting your embrace. This is just one masterpiece in the Museo del Prado, and its richness, significance, and symbolism could be studied for days. I invite anyone, whether a student or teacher of the arts, of history, of theology, or anything in between, to come and experience the embraceability Pacheco so strongly advocated for, embodied, or more appropriately incarnate in the dazzling work of Velázquez.