Casey Dawn Gailey, author

Dr. Elif Guler, faculty advisor

In 2006, the National Bullying Prevention Month campaign was established in the United States by the PACER (Parent Advocacy Coalition for Educational Rights) Center’s National Bullying Prevention Center. PACER, an organization that aims to help children and teens with disabilities, has recently expanded to incorporate the National Bullying Prevention Center for all youths suffering bullying in schools and elsewhere. This was one of the first major movements to prevent bullying in children and teens. Following this event, additional campaigns like STOMP Out Bullying and Disney’s “Choose Kindness” in 2014 have continued to increase awareness and the prevention of bullying, as well as to expand the fight against gender and sexuality prejudices and encourage belief of self-worth in children and teens. The campaigns released public service announcements and lead to various sub campaigns, such as STOMP Out Bullying’s Blue Shirt Day which encourages individuals to wear blue on a particular day in October to show support for anti-bullying movements.

Because the target audiences for such campaigns included children and teenagers, organizations also made other rhetorical attempts, especially in popular music. Around 2007, Disney started releasing commercials and music videos starring popular Disney celebrities like Selena Gomez, Demi Lovato, The Jonas Brothers and others speaking about various social campaigns like the Pass the Plate Magic of Healthy Living, green initiative and anti-bullying. The music video, “Who Says” by Selena Gomez & The Scene (2009) exemplifies rhetorical strategies in its support of the anti-bullying campaigns by advocating the value of inner-beauty over the more popular standards of physical beauty. In this paper, I will analyze “Who Says” as a visual artifact to explore its rhetorical value for subverting the popular standards of beauty—and thereby standing up against bullying in its various forms.

Rhetoric refers to the use of symbols to communicate and persuade or influence the thoughts or behaviors of an audience. This definition goes back Aristotle’s view of rhetoric as discovering all available means of persuasion in any given situation. Scholars, such as Roland Barthes and Keith Kenney, have recently elaborated this classical definition by examining how it applies to visuals. In order to analyze the visual rhetoric expressed in the music video of “Who Says,” I will first build on Barthes’s perspectives in his work, “Rhetoric of the Image,” with a particular focus on his notions of the linguistic, coded-iconic, and non-coded iconic messages. Put simply, the linguistic messages are verbal messages that accompany pictorial messages; the coded-iconic or denoted messages are the visual components explicitly expressed in a visual artifact; and the non-coded iconic or connoted messages are the meanings and associations audiences can draw from the denoted aspects (Barthes). These notions help examine the rhetoricity of the visual elements related to fashion and body, location, and signs as they are used in the video under analysis. After analyzing the linguistic, coded-iconic, and non-coded iconic elements in the video, I will also apply Kenney’s ideas in “Building Visual Communication Theory by Borrowing from Rhetoric,” on how visuals can form arguments in order to discuss whether the video “Who Says” may be considered a visual argument for the anti-bullying/inner-beauty social awareness campaigns. The rhetorical perspectives used for this analysis help us better understand how some of the prevalent visuals construct the video’s visual-rhetorical value and contribute to the plight of anti-bullying campaigns.

Rhetoric of Fashion and Body

At the beginning of the music video, “Who Says”, Selena Gomez is dressed in a black designer dress, jewelry, and bedazzled high heels with makeup on and her hair stylishly pinned up (Figure 1). Fittingly, the singer is in the midst of a photo shoot, with photographers and other members of the video crew directing her poses for the pictures. As the video continues, Selena’s posture and expression show frustration and awkwardness. Considering the music video as a rhetorical artifact, it is possible to apply Barthes’ messages to observe rhetorical implications of the images in these frames. Although the linguistic message is carried through the entirety of the video in the form of lyrics, I will disregard the song lyrics in order to focus on the visual aspects of this artifact. This initial scene provides many connotations, but principally, the outfit and accessories fit American society’s standards of beauty in how this wardrobe is comparable to what celebrities and models wear to events and for magazine spreads. As such, the singer’s attire is elevated into a symbol for conventional beauty.

Later in the video, the singer tosses the jewelry adorning her aside and removes her heels to run out of the posh studio and on to the city streets to escape the situation. The fact that she physically throws the jewelry aside, instead of just removing and handing it off to someone, and that she then completely flees the studio suggest both a literal and a symbolic rejection of the situation. Selena will not subject herself to the standards imposed upon her any longer.

The video continues with Selena walking barefoot through the streets of a typical downtown area, observing street signs (Figure 2). Eventually, her wardrobe transitions fully as she replaces the designer dress with casual summer clothes of jean shorts and a tank top with sneakers, while actively wiping off the remnants of cosmetics from the photoshoot – wiping away the conventionality to present herself unconcealed and beautiful for it (Figure 3).

Although one might argue that Selena’s choice of casual clothing also fits into social standards, in that the style of the jean shorts with pockets peeking out the bottom and the top were fairly conventional for teenage girls, this conventionality still supports the overall theme. The casual outfit is more symbolic of trying to associate Selena herself as just another teen girl – instead of a rich and attractive celebrity – so her intended message can better reach the audience. It is comparative to having a parent instruct a child not to do something, versus a peer instructing a child not to do something; children and young adults are more likely to listen to and believe a peer about how the world works, especially with regard to concepts like beauty which are highly subjective and can change with each generation.

Rhetoric of Location

Just like with fashion, this music video also demonstrates rhetoric pertaining to location. Just as Selena moves through the video, transitioning from the image conformity of the beginning to the freedom and acceptance of inner-beauty at the end, transitions of location parallel the argument. Selena starts at a high-end studio in the midst of a professional photo shoot. The room’s interior is very sleek and modern and is lit by artificial lights. It very clearly associates with the high-end, celebrity scene – with popular media, which is a fundamental basis for defining standards of beauty. After all, societies develop certain images as beautiful, because they are particular standards that reoccur in the media. A well-observed example is how American favoritism of skinny young women with flat bellies as models in magazines such as Seventeen or Vogue have propagated the idea that girls who are thinner, with more lithe physiques are lovelier than larger-sized young women. Thus, this opening location combined with Selena’s outfit acts as a symbol for society and socially defined beauty.

Of course, Selena flees this situation, yet again, and begins to meander down streets of some ubiquitous downtown area – with old brick storefronts and cracked, stained sidewalks. Then, she makes her way to a graffitied, industrial zone of the town. Basically, the location transitions further from the aesthetic locations – emphasizing just how far Selena is going away, literally and metaphorically, from social demands. All the while, Selena become progressively happier, taking bouncing steps and smiling more, despite the environment’s crudity.

In a stark contrast, after Selena changes her clothes, she moves to a waterfront. At first, it appears counter-intuitive as she previously withdrew from attractive locale. However, this final beach scene juxtaposes the opening scene entirely. Instead of wearing high-end fashion, she is dressed casually. Instead of bustling photographers crowding her, she is surrounded by other teenagers. Instead of remaining inside the modern studio, she is outside. Instead of seeking conventional beauty, she surrounds herself with the naturally occurring and nonconforming beauty of the earth.

Rhetoric of Signs – A Fusion of Linguistic and Pictorial Messages

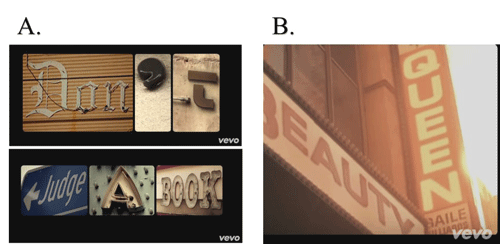

The purpose of the linguistic message, as Barthes describes, is to deepen the overall meaning of something, such as comic strips and videos. Here, the signs relay words and phrases to repeat Selena’s lyrics and emphasize idioms like “True beauty lies beneath the surface” and “don’t judge a book” as well as just “beauty queen” (Figure 4; Figure 5). What is more unique is how these linguistic messages are presented, and the connotations therefore derived.

Rather than just showing a line of text, or even just allowing the lyrics to provide any verbal message, the video uses cuts and fragments of road and business signs, compiled together into a collage of letters, which when observed together relate the words and phrases. For instance, one verbal collage uses nine different building and road signs to write out, “True beauty lies beneath the surface” (Figure 4). The typefaces and font sizes are different and many of the letters are worn down. For example, the sign spelling “true” is dirty and missing half the “r”, which is not necessarily aesthetically pleasing (Figure 4). And yet, this pictorial message makes the argument more poignant. The signs are ubiquitous visuals Americans see every day; they are not intentionally pretty, and each is unique. One association the audience might make is that the signs are like people in that they do not necessarily follow current social standards of what is attractive, yet they still have personality, uniqueness, and a natural inner-beauty that is outside of social norms. The use of the street signs for the verbal message that “true beauty lies beneath the surface” makes it much more evocative because of this connotation. Additionally, signs by basic nature direct or command people. Signs relate what a building is, what the street is, where you can get gas or food, how fast to drive, and etcetera. This imperative nature of signs leeks into the connoted message – dictating that you should observe the messages to be true such that the audience should believe that true beauty really does lie beneath the surface.

The Possibility of an Argument

Kenney suggests that visuals “can be said to persuade by argument when we have the ability to choose” and to be an argument, visuals must also do three things. Firstly, the visuals must “provide reasons for choosing one way or another”; secondly, the visuals “counter other arguments”; and lastly, the visuals “cause us [the audience] to change our beliefs or to act” (Kenny 58).

Drawing upon Aristotle’s classical definition of rhetoric, as well as Barthes’s and Kenney’s ideas about visual rhetoric, “Who Says” appears to have both communicative and persuasive functions. According to Kenney’s first requirement for an argument, there are two choices blatantly offered in the music video under analysis: the choice to conform to social standards of beauty or the choice to disregard such norms and to instead believe that all people naturally have a form of inner beauty. The video appears to favor the latter choice, of inner beauty, by countering the social argument for conventional beauty. From the beginning of the video, the main premise is that “conforming to society’s ideas of beauty is stressful and uncomfortable.” The counter to this social conformity is thus when Selena rejects the ensemble and its social implications by changing into casual clothing, after which she is visually happier and more relaxed as she joins peers to celebrate on a beachfront. This counter provides the premise that “it is better to dress freely (without worrying over social image beliefs) and be happy, than to conform and be pretty, but unhappy.” Overall, the music video, “Who Says”, attempts to successfully influence the audience by urging them into accepting the belief that beauty is not skin-deep; it is not socially defined. Beauty, instead, is internal and ubiquitous.

Works Cited:

Aristotle. Rhetoric. Trans. Edward Meredith Cope. 1877. Ed. John Doe. New York: Philosopher’s Attic Press, 2010. Print.

Barthes, Roland. Rhetoric of the Image. N.p.: n.p., 1993. Print.

Kenney, Keith. “Building Visual Communication Theory by Borrowing from Rhetoric.” Journal or Visual Literacy 22.1 (2002): 55-80. Print.

PACER Center. “History and Impact.” PACER’s National Bullying Prevention Center. PACER Center, Inc., n.d. Web. 19 Oct. 2015.

SelenaGomezVEVO. “Selena Gomez & The Scene – Who Says.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 4 March 2011. Web. 19 Oct. 2015.