Age: 20 (Division 1 college student-athlete)

Athletic Identity: Division 1 Track & Field Runner (specializing in the 800m, nationally ranked in high school, scholarship athlete at Longwood University)

Gender Identity/Expression: Male

Race/Ethnicity: White, Italian

National Origin: United States of America

Sexual Orientation: Heterosexual

Relationships: Supportive boyfriend in a committed relationship with my girlfriend; close bonds with family, teammates, coaches, and friends

Mental/Physical Ability: Physically able, strong athletic performance, live with mental health challenges that have shaped resilience

Values/Mantra: “To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift” – Steve Prefontaine

Community/Environment: Strong connection to supportive coaches and teammates at Longwood, value of individualized training, and a close-knit community

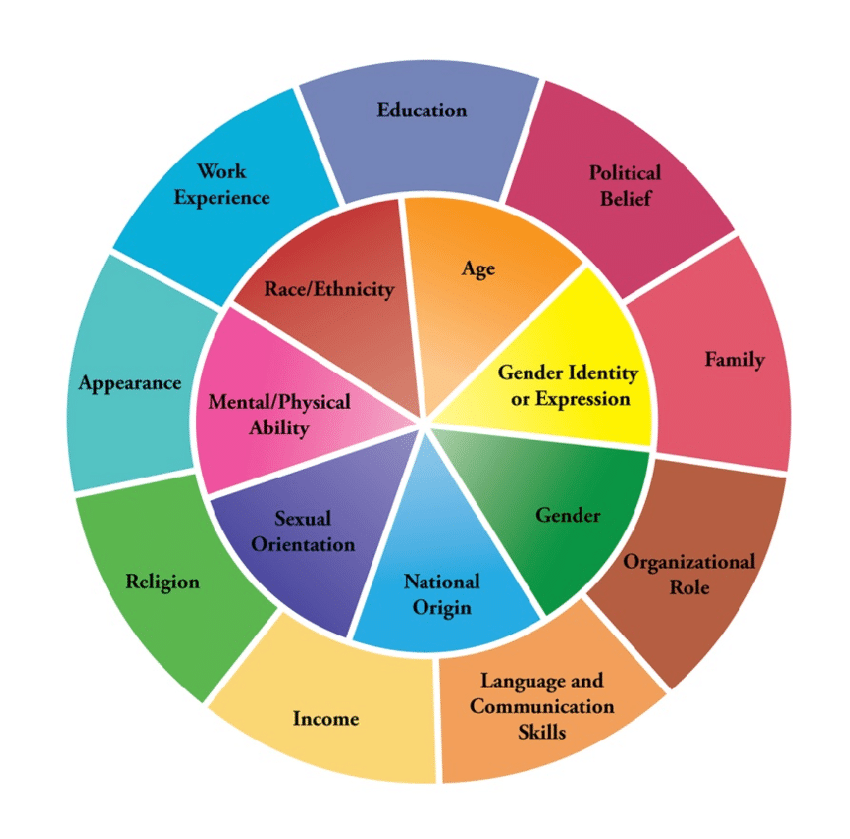

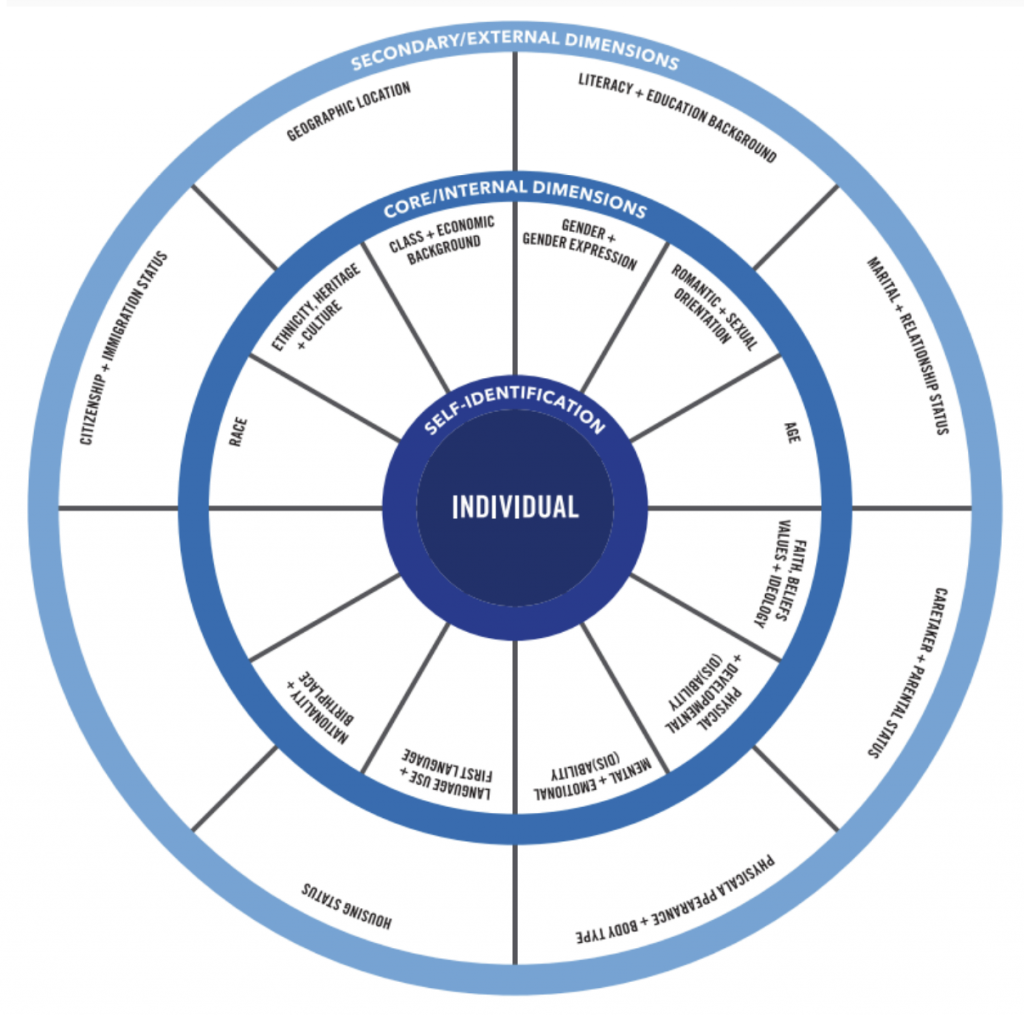

Identities

The identities that push me to grow and connect with others are the ones I value most. My athletic identity as a Division 1 runner has shaped nearly every part of who I am. It keeps me disciplined, driven, and constantly striving to improve. It also connects me with teammates who understand the grind, the sacrifices, and the relentless pursuit of excellence. My Italian heritage also plays a role in my sense of identity and connection. Family, tradition, and loyalty are all values that have shaped how I move through the world. It gives me pride in my roots and helps me see myself as part of something larger than just my own individual experiences. My mental health journey is another important piece. Living with challenges in this area has been tough, but it’s made me more resilient. It’s given me perspective on struggle, empathy for others, and the motivation to keep finding meaning in my relationships, my sport, and my life. While difficult, these challenges have pushed me to grow into a stronger, more purposeful version of myself.

Identities & Self Concept

Being male has shaped how I connect to others through competition, teamwork, and leadership. Athletics has given me a brotherhood of teammates who push me, support me, and inspire me to be better every day. These relationships have strengthened my self-esteem and helped me understand how much I matter in the lives of those around me. My Italian background adds another layer to how I see myself and connect with others. The cultural emphasis on family, food, and loyalty has helped shape my values, reminding me that relationships and connections matter just as much as individual achievements. My girlfriend has also played a major role in shaping my self-concept. Being in a loving, supportive relationship motivates me to be the best version of myself, not just for me but for her, too. Her encouragement helps me during challenges, and I try to give that same support back. My mental health struggles have tested my confidence, but they’ve also forced me to build tools and strategies that make me stronger. With support from my family, girlfriend, coaches, and friends, I’ve learned that my value doesn’t just come from my performance—it comes from who I am as a person. That realization has helped me balance my self-concept and find meaning beyond the track. My athletic identity ties directly into this. Competing at the Division 1 level has tested me in every way—physically, mentally, and emotionally. Training and racing have shown me my limits, but also that I can push past them. Running has become more than a sport; it’s a core part of how I see myself: someone who refuses to give less than his best.

Career & Identity

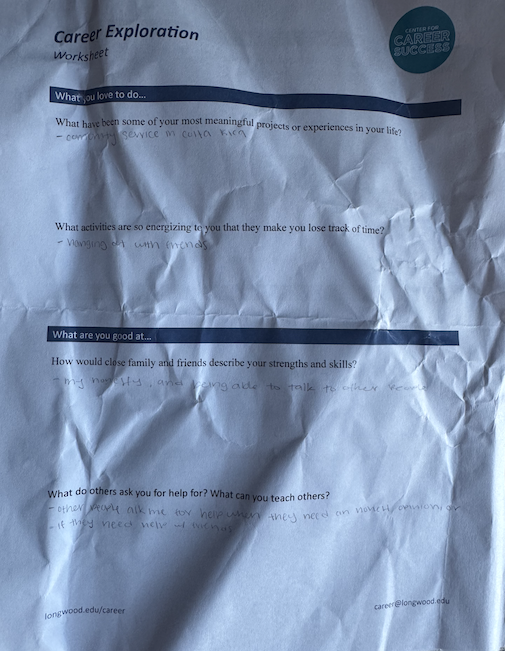

What have been some of my most meaningful projects or experiences in my life?

- Earning a Division 1 track and field scholarship and competing in the 800m.

- Overcoming setbacks while training on my own for two years before transferring to Longwood.

- Mentoring younger athletes and teammates by sharing training strategies and motivation.

What activities are so energizing to me that they make me lose track of time?

- Running, training, and analyzing race strategies.

- Coaching and giving advice to teammates.

- Watching professional track meets and studying performances.

- Spending time with my girlfriend and close friends.

How would my close family and friends describe strengths and skills?

- Disciplined and driven.

- Resilient, able to bounce back from challenges.

- Supportive and encouraging to others.

- Outgoing and passionate.

What do others ask my help for? What can I teach others?

- Advice on running, training, and pacing.

- Motivation and mental toughness strategies.

- General support and encouragement during stressful times.

- Tips on balancing athletics, school, and personal life.

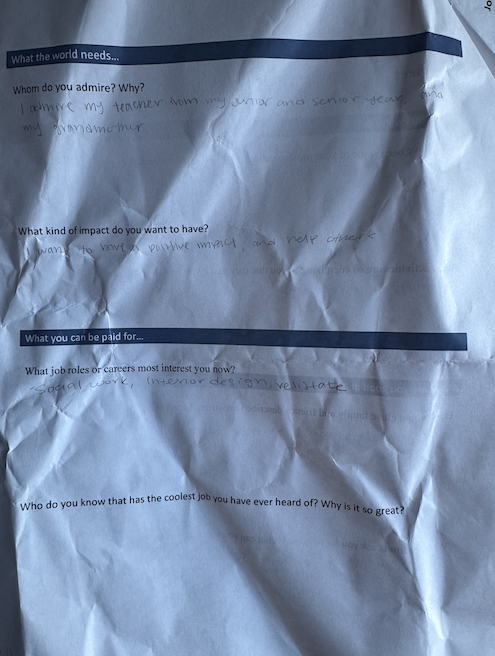

Whom do I admire? Why?

- My parents: for their resilience, sacrifices, and ability to always keep moving forward.

- My girlfriend: for her support, open-mindedness, and ability to stay strong in adversity.

- My coach: for believing in me and creating a supportive, individualized training environment.

- Professional runners: for their dedication to excellence and pushing human limits.

What kind of impact do I want to have?

- Inspire athletes to push their limits and realize their potential.

- Build a culture of support and discipline where athletes feel valued.

- Show others that setbacks don’t define them—it’s how they respond that matters.

What job roles or careers most interest me now?

- College and professional track/cross-country coach.

- Possibly starting my own running club or training program in the future.

What is the coolest job I have ever heard of? Why is it so great?

Sports psychologist: because mental toughness is such a huge part of athletics, and helping athletes unlock that could be life-changing.

Olympic or professional coach: because you get to shape elite athletes and play a direct role in world-class performance.

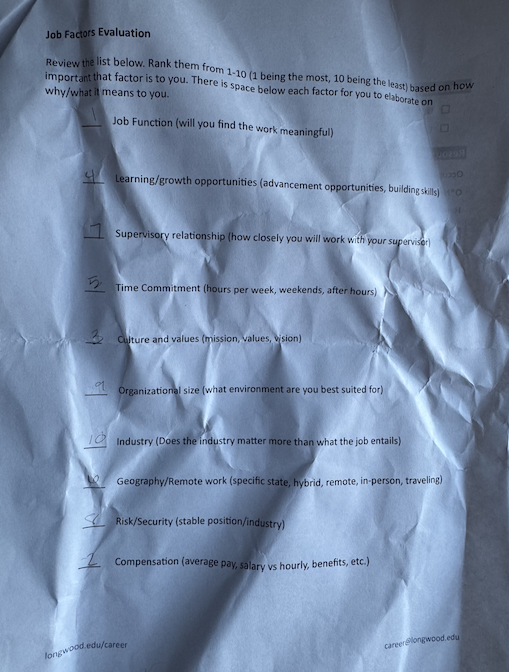

My Job Factors Evaluation (1 = most important, 10 = least important):

- Job Function (Will you find the work meaningful?)

- Culture and Values (Mission, values, vision)

- Learning/Growth Opportunities (Advancement opportunities, building skills)

- Supervisory Relationship (How closely you work with your supervisor)

- Risk/Security (Stable position/industry)

- Time Commitment (Hours per week, weekends, after hours)

- Compensation (Average pay, salary vs. hourly, benefits, etc.)

- Organizational Size (What environment you’re best suited for)

- Industry (Does the industry matter more than what the job entails)

- Geography/Remote Work (Specific state, hybrid, remote, in-person, traveling)

Professional Self

Purpose to Work

My purpose to work is rooted in my drive to reach the top of the sport I’ve dedicated my life to. As a Division I track and field athlete on scholarship, I’ve experienced what it takes to train and compete at an elite level. My biggest goal is to run professionally and test myself against the best in the world to see how far my discipline, belief, and work ethic can take me. Beyond competing, I’m equally driven by the goal of becoming a coach who can bring others to that same level. I see my journey as an athlete not only as personal growth, but as preparation to teach the next generation. Every training cycle, every race, every setback adds to the knowledge I’ll get to use one day to develop and mentor others. Competing as a professional will give me a deeper understanding of what the world’s best athletes experience and how to deal with the mental/physical demands, sacrifice, and the mindset needed to stay there. I want to take that experience and turn it into lessons for young runners who dream just as big as I do. Coaching at the Division I and professional levels would allow me to build a legacy that continues long after I’ve finished racing, shaping athletes who carry that same need for glory. I work not only to achieve my own goals, but to build a standard that others can follow and surpass.

What Motivates Me

I’m motivated by competition, improvement, and impact. Every day I train, I’m chasing fractions of a second pushing myself toward something greater. Knowing I’m a Division I athlete on scholarship motivates me to honor the opportunity I’ve been given and to make the most of it. I’m also motivated by the idea that my effort and success can influence others. I want to show that with the right mindset, dedication, and resilience, you can climb from the collegiate level all the way to the professional stage. A big part of my motivation comes from Steve Prefontaine’s quote: “To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift.” That line has stuck with me since the first time I read it. It’s become my personal mantra. It reminds me that talent means nothing without total commitment, and that every day is another chance to use the gift I’ve been given to its fullest extent.

Jobs and Experiences That Made Me Feel Fulfilled

Working full time as a USA Swim coach for two years gave me the chance to see development from a different perspective. I found fulfillment in watching athletes reach goals they once thought were impossible. Exactly like I’ve experienced in my own training. I have also coached middle school runners and mentored high school athletes. These two have allowed me to translate my college level experience into lessons that mattered to them. In addition i have connected with professional runners through Zoom calls and in-person conversations which have given me insight into the reality of the professional world. Specifically what it demands, how to prepare, and what separates the good from the great. These experiences have made me more confident that I’m on the right path to competing at the highest level and eventually coaching there too.

What I Enjoyed in My Work and Volunteer Experiences

I’ve enjoyed building athletes up, not just physically but mentally as well. I love seeing their belief in themselves grow with each workout. I enjoy creating personalized training plans, analyzing splits, and finding small ways to help them break through limits. I also love being around people who share that same hunger for improvement. Whether I’m in the weight room, on the track, or at a meet, that environment of hard work and shared goals always keeps me inspired.

What I Did Not Enjoy in My Work and Volunteer Experiences

One thing I don’t enjoy is seeing athletes limit themselves through doubt. It’s something I recognize because I’ve faced it too. In addition I also struggle when outside issues like poor organization or lack of support from those around them hold athletes back from reaching their potential. Lastly, I’ve learned that coaching can make it hard to balance personal training with mentoring others, but I see that challenge as something that’s preparing me to manage both when I transition from being an athlete to a full-time coach.

Hard and Soft Skills

Hard Skills: Training and performance design, biomechanics and race strategy, and advanced conditioning techniques.

Soft Skills: Leadership, communication, and motivational coaching.

What Others Would Say I’m Good At

People would describe me as confident, competitive, and genuine. My confidence comes from preparation. I trust the work I put in and the process I follow every day. These beliefs however don’t just apply to me though. I also believe in others, but only in those who truly put in the work. I’ve always respected effort and dedication, and I normally connect the most with people who share that same mindset. Teammates often tell me I lead by example and bring intensity into everything I do. Whether it’s a hard practice, a race, or helping a teammate through a rough patch, I stay locked in and focused on solutions rather than just staying motionless. Coaches would describe me as consistent and hungry. Someone who wants it more than others and is willing to do whatever it takes to get there. I’m also naturally competitive both with myself and with others. I see competition as a form of respect because giving your best effort pushes everyone to a higher level of excellence. That drive, combined with my belief in discipline and accountability, is what I think separates me. Friends and mentors often say that my drive and ability to hyper focus on what I want is what makes me stand out, both as an athlete and as a future coach.

NACE Career Competencies

Leadership

Being a D1 athlete has taught me the importance of leadership through action. On my team I’ve always tried to lead by example, showing up every day prepared, focused, and willing to push myself and others. Leadership isn’t just about being vocal it’s about being consistent, trustworthy, and willing to take responsibility for my own work. Coaching youth athletes also showed me how leadership can be about encouragement and accountability. Really trying to find the right way to push each person to reach their potential.

Communication

Communication has been key in every coaching role I’ve had. Whether it’s explaining drills to swimmers, breaking down race strategy for middle school runners, or giving feedback to a teammate. With this I’ve learned that clarity and tone matter. Good communication is about listening as much as it is about speaking. I make sure I understand what someone needs before giving advice to them, and I try to tailor my approach so it helps them improve without feeling criticized to a certain degree.

Professionalism

Balancing academics, athletics, and coaching has built my sense of professionalism and discipline. I’ve learned to show up on time, stay focused, and maintain a high level of effort even when things get difficult. Competing as a D1 athlete means performing under pressure and staying accountable to others. That mindset carries into everything I do. Whether I’m training, working, or mentoring I bring the same work ethic. I am always giving my full effort and trying to represent myself and my team the right way.

Critical Thinking

In both running and coaching, critical happens constantly. Training plans change, athletes hit plateaus, and sometimes races don’t go as expected. I’ve learned to adjust, analyze, and respond instead of reacting emotionally. I use feedback, data, and observation to figure out what’s working and what’s not. That process helps me improve performance, prevent injury, and stay calm in high stress situations. Critical thinking in athletics is about understanding the why behind the what and that’s something I carry into every challenge I face.

Resume

Chris Smith

Longwood University — Division I Track & Field Athlete

Farmville, VA | Chris.Smith@live.longwood.edu | 757-775-1910

Objective

As a Division I middle distance runner and Health and Physical Education major, my goal is to continue building my career toward becoming a full time coach. Competing at the highest collegiate level has given me firsthand knowledge of what it takes to train, lead, and motivate athletes. I want to use that experience to help others reach their potential both in performance and personal growth.

Education

Longwood University (LU)— Bachelor of Science in Health and Physical Education Expected Graduation: May, 2028.

- NCAA Division I Track & Field Scholarship Athlete (800 meters)

- Coursework in exercise physiology, coaching methods, kinesiology, and human development

- Emphasis on promoting health, fitness, and athletic performance through education and leadership

Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) — Transferred

- Competed in Division I Track & Field prior to transferring to Longwood

- Gained experience in collegiate-level competition and structured training programs

Coaching & Leadership Experience

USA Swimming Coach — Full Time Coach

Williamsburg, Virginia | 2 Years

- Coached athletes of varying levels, focusing on stroke efficiency, conditioning, and race preparation

- Created detailed training plans and individualized goal programs

- Encouraged a positive mindset and helped athletes manage nerves before competition

- Learned how to connect with parents, athletes, and staff to maintain a strong team culture

Middle School Track Coach / High School Mentor

Williamsburg, Virginia | 2 years

- Introduced athletes to structured running workouts, pacing, and recovery principles

- Focused on technique, discipline, and developing confidence in competition

- Adapted collegiate-level knowledge to middle and high school training environments

- Mentored athletes pursuing college-level opportunities

Athletic Background

- NCAA Division I athlete specializing in the 800 meters

- National Top 10 ranking in high school

- Scholarship recipient at both VCU and Longwood

- Experienced in advanced training methods, biomechanics, and race strategy

- Known for leadership, accountability, and mentorship within the team

Skills

- Coaching and athlete development

- Race planning and performance tracking

- Leadership and team motivation

- Strength and conditioning fundamentals

- Communication and mentorship

- Organization and goal setting

Certifications

- CPR and First Aid Certified

- SafeSport Certified (in progress or planned)

- USA Track & Field Level 1 (in progress or planned)

Coaching Philosophy

“To give anything less than your best is to sacrifice the gift.” — Steve Prefontaine

I believe that great coaching is about helping people become their best selves on and off the track. Every athlete deserves a coach who believes in them and shows up every day with purpose and care.

Cover Letter

Chris Smith

Farmville, VA Longwood University

Chris.Smith@live.longwood.edu

757-775-1910

10/08/2025

Hiring Committee

Penn State University Athletics

State College, PA

Dear Hiring Committee,

I’m writing to apply for the Part-Time Track and Field Assistant Coach position at Penn State University. As a current Division I track and field athlete and someone who plans to run professionally, I’m deeply committed to the sport and passionate about helping others reach their full potential. Coaching is something I’ve grown into over the years, and this position would be a great step toward my long-term goal of becoming a full-time coach. I’ve spent two years working full-time as a USA Certified Swim Coach, where I designed workouts, motivated athletes, and learned how to adapt training to different skill levels. I’ve also coached middle school runners and mentored high school athletes, helping them build confidence, improve form, and set goals. Talking with professional runners both online and in person has shown me what it really takes to succeed at the top level, and I bring that same focus and discipline to my athletes. I’m currently earning my Bachelor’s degree in Health and Physical Education at Longwood University. My studies give me a strong understanding of exercise science, biomechanics, and athlete development, which I apply to my coaching every day. People often describe me as confident, competitive, and motivating. I believe in every athlete who’s willing to put in the work, and I try to lead by example showing what commitment and consistency look like in action. I would love the chance to bring my energy and knowledge to Penn State’s program. I’m ready to help with training, mentoring, and supporting the team’s goals in any way I can. Thank you for your time and consideration. I’d be honored to be part of your coaching staff and continue growing as both an athlete and coach.

Sincerely,

Chris Smith