Throughout the years, Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise has been celebrated as the quintessential symbol of the Impressionist Movement. This renowned work of art which illustrates a view of the port of Le Havre in north-western France is considered to be one of Monet’s “most poetic expressions” of his engagement with France’s revitalization efforts after the Franco-Prussian War.[1] Unlike other artworks of the time, the subject matter and specific painting techniques evident in Impression, Sunrise seek to transcribe the feelings initiated by a scene rather than simply rendering the details of a particular landscape. This act of expressing an individual’s perception of nature was a key characteristic and goal of Impressionist art, and is a common motif found in Monet’s paintings. While Impression, Sunrise and Monet’s artistic technique fell under harsh criticism at their outset, Monet’s masterpiece gave birth to a new movement and created a revolution in the world of art.

Widely regarded as Monet’s single most famous painting, Impression, Sunrise was completed during the late nineteenth century in 1872. The most significant aspect of the painting is its credit with giving the Impressionist Movement its name. When the painting was first shown to the public in the L’Exposition des Révoltés—an exhibition independent of the Salon that was organized by Monet, Bazille, Pissarro, and their friends—many critics were extremely disapproving of the rebel group’s work, especially that of Monet.[2] In the April issue of Le Charivari, a critic named Louis Leroy judgmentally entitled his article “Exhibition of the Impressionists,” thereby coining the term inspired by the title of Monet’s work Impression, Sunrise. Although this oil painting was disparaged during the time of its creation, today it is viewed as an austere example of the mindset and purpose behind Impressionism. Currently, Impression, Sunrise is located in the Musée Marmottan in Paris, France.[3]

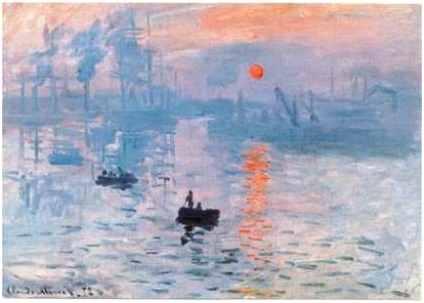

The imagery of this work of art presents a focus on the calm feeling of a misty maritime scene. Slightly below the center of the painting, a small rowboat with two indistinct figures floats in the bay. The early morning sun is depicted rising over the foggy harbour with ships and other various boats at port. The shadows of the boats and figures and the reflection of the sun’s rays can be seen on the water’s surface. Monet incorporates a palette of mostly cool, dull colors into the painting with blues and grays, but also includes splashes of warm colors noticed in the sky and the red-orange sun. This usage of a noticeably bright color draws attention to the main focus of the painting, the sun. Numerous vertical elements can be found throughout this hazy landscape. To the left of the center of the canvas, a four-masted clipper ship enters the harbor while smoke-stacks of steamboats fill the atmosphere. Cranes and heavy machinery can be detected to the right side of the painting. The emissions of the factories, ships, and machinery mix with the early rays of the sun to generate a sort of beauty that is “both surprising and seductive.” [4] Off in the distance, more vertical forms break the horizon—chimneys of various factories and masts of other ships may be observed.

Through the examination of specific characteristics apparent in the painting, we are able to identify the distinguished artistic style of Monet. As a notable artist, Claude Monet was acknowledged for his awareness of color harmony and his ability to enforce viewers’ attention. He was widely known for capturing rich atmospheric effects and a particular moment in time in his works of art.[5] To accomplish these feats, Monet employed broken brushwork and heightened color. He was also very sensitive to the moods created by a landscape; in his own words he explained his method of depicting the feeling of a scene:

When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have in front of you, a tree, a field…Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives your own naïve impression of the scene.[6]

Throughout his work, Monet maintained an imaginative grasp of the essential structure and pattern of the subject he was painting. Other artists such as Boudin, Jongkind, and Courbet had a strong influence on this ability of Monet’s, which can be recognized in his landscape paintings made during the fifteen-year span of 1865-1880.[7] He was capable of extracting meaningful design from apparently casual scenes, thereby emphasizing the true nature of a place. This manner of illustration can be seen in Impression, Sunrise—he places an accent on the fogginess of the harbor that is created by the smoke from the steamboats, which relates to its chief status as a major trading port.

An important part of Monet’s artistic style was the way in which he transformed an outdoor painting into a finished masterpiece. Every painting Monet created had to meet a certain criteria before he could begin to consider it a finished piece, and even then he could find the potential for change and growth in a painting and deny its completion—“Anyone who says he has finished a canvas is terribly arrogant.” [8] Using different terms to distinguish each step, Monet followed a precise process in order to make his paintings. The beginning step was called the croquis which defined the first outline of the artist’s first idea actually drawn out on paper or canvas. He referred to the second step as the esquisse which was a quick, small trial work focused on the painting’s composition. The esquisse was characterized by a free and bold handling of the pen or brush and expressed the “heat of improvisation.” [9] The next stage of a painting was named ébauche, used to describe the first real painting done on the canvas that evolves into the completed work in the end of the process. Pochades, the fourth step, were viewed as draft works that were abrupt but performed with more care and attention than an esquisse. Monet explained his fifth stage of a painting as an etude, a work painted entirely outside but not deemed a finished painting. Closely related to etudes were impressions, the step that Impression, Sunrise refers to. Impressions were stages of a painting used to capture natural effects and the emotions radiated by an outdoor scene. The tableau was the last stage of the painting process and considered the final product which needed no other preparations.

Over time, Monet’s painting techniques evolved and matured from the type he implemented in Impression, Sunrise to that seen in his later, larger paintings such as his water lilies. One area in which he developed his technique was pigment mixture. While Impression, Sunrise displays several different tones of color, Monet’s later works exhibit a wider variety of color juxtaposed against one another. Monet would come to use layer upon layer of paint in his future paintings. He applied many layers to succeed in creating the perfect combination of pigment, but also to cover undesired portions when he changed his mind in the process of completing a painting, which happened often. Up to fifteen layers of paint have been counted in a cross-section by scientists who have analyzed Monet’s paintings.[10] Another future technique not seen in Impression, Sunrise that Monet employed was corrugation. This technique is seen in several of his water lily paintings. The effect of corrugation was produced by layering thick, but open brushstrokes of paint onto the canvas which then served as the textural basis for the thin strokes of color placed on top. Monet applied these thin strokes perpendicularly to the under-layer so as to lightly brush the ridges of the texture. If Monet acquired layers of paint that were too heavy, he often used a technique called scraping down to remove the unwanted or excess paint. A final technique Monet later utilized in his water lily paintings was named leaching. In this process, Monet would squeeze the paint out of the tubes onto paper blotters to drain the oil from the paints. This technique was commonly used when he desired a softer and more matte-like appearance.[11]

Because Impression, Sunrise is regarded as the painting that gave birth to the Impressionist Movement, we can clearly observe specific details in this work of art that allude to its Impressionist style. An important characteristic of Impressionist painting is the type of brushstrokes utilized. Short, thick strokes of paint are applied to the canvas to quickly capture the essence of the subject. The brushstrokes visible in the water in Impression, Sunrise create a sense of rhythm which reflects the feeling produced by the motion of the sea. Another feature of Impressionist painting was the distinct application of color. Colors are placed side by side and are mixed optically by the viewer’s eye. This technique is evident in the sky and water portions of Impression, Sunrise. Lastly, Impressionist painters consigned heavy emphasis on natural light—a practice that can be detected throughout Monet’s work including the sunlight reflection in this particular artwork. To achieve this natural ambience of light, he often mixed his pigments with large amounts of lead white.[12] During his career, Monet’s innate skill to capture this effect was recognized through his reputation as the “incomparable painter of [. . .] light.” [13]

There are many cultural influences that permeate Impression, Sunrise. The masterpiece is a combination of two themes in landscape painting that would have been extremely familiar during the late nineteenth century. Scenes of sunrises and French ports were subjects that were commonly portrayed in artworks of this time; therefore Monet’s decision to combine these two topics is logical.[14] We can also explain his choice of subject matter through his own personal background. Le Havre port, the one seen in Impression, Sunrise, was located in Monet’s hometown. He was extremely familiar with this area of France and had special connections to the harbor itself. Therefore, viewers and researchers can clearly recognize why he would select this location as the main subject in many of his works.

One cultural event that had an immense effect on the artwork of Monet was the Franco-Prussian War. Lasting from 1870-1871, the war was a conflict between the Kingdom of Prussia and the Second French Empire. France ultimately lost the war, marking the end of Napoleon III’s empire, and was forced to relinquish the territory of Alsace-Lorraine to Prussia. While the war only lasted a year, the results of the war were damaging to French government, society, and morale. As France began its recovery from the war, individuals began to unite for the purpose of reconstructing the nation. Monet had a heavy engagement with the revitalization of French pride and spirit, depicting his fervor in many of his paintings made at that time. In particular, his Impression, Sunrise strongly emphasizes France’s determination to rebuild and recover from the devastation of the war.[15] Since the 1850s, Le Havre had slowly grown to become the second largest port of France. In Impression, Sunrise, Monet’s inclusion of many large ships in the painting depicts this fact. After the Franco-Prussian war, however, the harbor experienced a more steady increase in population and business. The expansion of the port was seen in the early 1870s as a testimony to France’s post-war renewal.[16] At the time of Impression, Sunrise’s creation, Le Havre harbor was the site of many of the city’s largest and most important industries. Many indications of this fact can be found in Monet’s painting. The haziness in Impression, Sunrise is due not only to the morning mists of the channel, but also to the emissions produced by factories and steam ships. The heavy machinery noticeable in the artwork was part of a construction project that was taken up following the armistice signed between Prussia and France.[17] Although it is hard to believe an industrialized, smoggy scene could be viewed as one of beauty, to the people of the time like Monet, this scene would have been a source of inspiration for the prosperity of the future.

At the height of Impressionism, critics and artists began to doubt whether or not the movement would have a lasting effect and value. Even Monet, the most highly regarded Impressionist painter and leader of the style, questioned the permanence of his work.[18] It was around this time that Monet’s subject matter and method of painting somewhat changed. He began to depict objects that held more religious and historical significance, such as his “Liberty Trees” paintings, which referred to the trees that people planted during the French Revolution to signify French democracy.[19] By illustrating items that had important connotations, Monet hoped to bring a similar importance to Impressionism. He also started painting the same objects or scenes over and over again, but at different times of the day. This method is manifested in his series paintings, such as his grain stacks, water lilies, and the Rouen Cathedral in northwestern France. While these series represented his interest in light effects, they also symbolized Monet’s attempt to find stability in his artwork.[20]

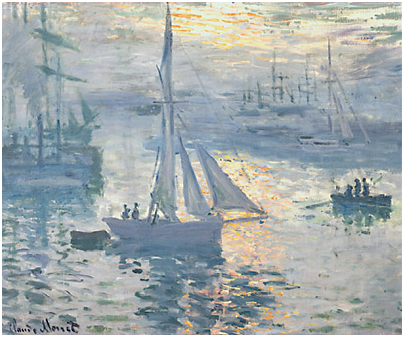

Over the centuries, people have been certain that Impression, Sunrise was the masterpiece that inspired one of the most important art movements ever known. However, some researchers have recently speculated whether or not Impression, Sunrise was in fact the painting that was associated with the start of Impressionism.[21] These experts claim that the description from the first Impressionist Exhibition does not match that of Impression, Sunrise, but instead that of another of Monet’s paintings—Sunrise (Marine), seen below:

This painting is supposed to have been created during the early spring of 1873, placing it around the same time as the production of Impression, Sunrise. Some researchers believe the target of Louis Leroy’s criticism has been confused over the years and was always meant to be Sunrise (Marine). They argue that Impression, Sunrise was not shown in the first exhibition in 1874, but was instead only shown in the fourth show of 1879. They also state that Impression, Sunrise does not illustrate a rising sun, but in fact a setting sun as it would look through fog. Therefore, they assume Impression, Sunrise cannot be the painting described in the critic’s original article. They do however believe that Sunrise (Marine) unmistakably depicts a rising sun and correctly corresponds to the measurements cited in Leroy’s article, so thus they consider it is the true painting that inspired the Impressionist movement.[1]

Although criticism and uncertainty about Impressionism surfaced during its practice, there is no hesitation existing today concerning the vital impact that this movement had on the world of art. Monet, the chief painter of the Impressionist Movement, can be credited with much of the style’s success and notoriety. His masterpieces, especially Impression, Sunrise, excelled in expressing one’s perception of nature which came to be the essential goal of Impressionist art. Monet’s avant-garde approach to painting the feelings emitted by a scene rather than exact details paved the way for advancements in technique that led to the evolution of modern art.

Bibliography

Dunstan, Bernard. Painting Methods of the Impressionists. New York: Watson-Guptill

Publications, 1976. Print.

Gunderson, Jessica. Impressionism. Mankato: Creative Education, 2009. Print.

Heinrich, Christoph. Claude Monet, 1840-1926. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH,

2000. Print.

House, John. Impressionism: Paint and Politics. Singapore: John House, 2004. Print.

House, John. Monet: Nature into Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 1988. Print.

Lyon, Christopher. “Unveiling Monet.” MoMA 7 (1991): 14-23. Print.

Patin, Sylvie. Monet: The Ultimate Impressionist. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993. Print.

Southgate, Therese. “Sunrise (Marine).” The Journal of the American Medical Association

291.21 (2004). Print.

Taillandier, Yvon. Monet. New York: Crown, 1988. Print.

Tucker, Paul H. Claude Monet: Life and Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. Print.

Footnotes

[1] Tucker, Paul H. Claude Monet: Life and Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. Print.

[2] Patin, Sylvie. Monet: The Ultimate Impressionist. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1993. Print.

[3] Taillandier, Yvon. Monet. New York: Crown, 1988. Print.

[4] Tucker, Paul H. Claude Monet: Life and Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. Print.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Dunstan, Bernard. Painting Methods of the Impressionists. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1976. Print.

[7]Ibid.

[8] House, John. Monet: Nature into Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 1988. Print.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Lyon, Christopher. “Unveiling Monet.” MoMA 7 (1991): 14-23. Print.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Heinrich, Christoph. Claude Monet, 1840-1926. Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, 2000. Print.

[14] House, John. Impressionism: Paint and Politics. Singapore: John House, 2004. Print.

[15] Tucker, Paul H. Claude Monet: Life and Art. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. Print.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Gunderson, Jessica. Impressionism. Mankato: Creative Education, 2009. Print.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Southgate, Therese. “Sunrise (Marine).” The Journal of the American Medical Association 291.21 (2004). Print.

5 Responses