Abstract

Striking information from the record, as instructed by a judge, is a procedure heavily relied upon in the legal system, yet there is little evidence to support the procedure as successfully removing this information from consideration by the jury. Two scenarios of different degrees of severity, defense-stricken, defense, and no defense (control), were therefore considered in which the defendant’s guilt was judged by participants. Two groups were presented with the defense. The first group was instructed to strike specific information from the record while the second group received no such instructions. A third group acting as a control was presented with no defense. Results showed participants attributed similar degrees of guilt to the defendant in the defense and defense stricken groups, both of which were significantly higher than the control (no defense) group. These results support the premise that though information may be stricken from the record it does not mean it is objectively stricken from memory.

Keywords: Guilt, Information Stricken, Legal System, Direct-forgetting, Jury Memory

Introduction

Much is unknown about the capability of a juror to objectively strike information from memory, yet the United States Legal System relies heavily on the ability to strike a statement from the record. With individual freedoms at risk, it is imperative to ensure that this process is thoroughly researched and not inadvertently impeding our discovery of the truth as to the defendant’s guilt or lack thereof.

Research has produced two theories that clearly relate to the ability of jurors to strike information from memory: (1) the influence of psychological reactance and (2) the Ironic Process of Mental Control. According to the theory of psychological reactance, commonly known as the reactance theory, jurors with a high reactance propensity can experience discomfort when their control over their ability to use any and all information presented during the case is limited or diminished entirely. This limit to what they view as their right and freedom to consider all evidence presented may cause these jurors to ignore the judicial admonition and continue to include inadmissible evidence during deliberation. However, those jurors with low reactance propensity have a much easier time suppressing this discomfort therefore allowing them to follow the judge’s instructions to disregard inadmissible evidence or statements (Jonas, 2007).

Proponents of the Ironic Process of Mental Control believe that attempts at suppression can actually increase the accessibility of the information being suppressed. According to this theory, the overload in cognitive functioning used to make important decisions such as the guilt or innocence of a defendant can cause the suppressed information to become more frequent in the forethought of the juror, thereby making it much harder to ignore (Jonas, 2007).

Similarly, and perhaps one of the more alarming discoveries, is the backfire effect revealed by Cox and Tanford (1989). This effect shows the tendency for jurors to inadvertently pay greater attention to inadmissible evidence or information they have been instructed to disregard. In their study, participants paid greater attention to the information when a judicial admonition was given and were also prone to harsher judgments and negative character traits in regards to the defendant’s credibility. It is believed that since a judicial admonition brings the inadmissible evidence to the attention of the jurors, then that information will become more evident in the jurors mind during deliberation as opposed to when it was not specifically brought to their attention.

Directed forgetting has several premises, which may shed light on the potential of a jury member to disregard information. One premise suggests that once the presented information has helped to influence a new possible explanation for a behavior, it is much more difficult to strike the information from memory (Golding, 1998). On the other hand, if the presented information is considered to be irrelevant or only slightly influences the case at hand, then it is much more likely that the juror will be able to disregard the statement (Golding, 1998).

Sue, Smith, and Caldwell (2009) completed an experiment that produced results contrary to directed forgetting. In this study the strength of evidence and its influence on juror bias was examined when participants were presented with evidence of varying significance to the trial at hand. When the participants were introduced to evidence that had a strong relation to the trial but then were instructed to disregard the information, there was little bias shown amongst the verdicts. However, jurors were more prone to be influenced by evidence that was characterized as weak or circumstantial. In these cases, jurors gave a higher number of guilty verdicts (Sue et al., 2009).

A study completed by Rind, Jaeger, and Strohmetz (1995) examined the effect of the seriousness of the offense on juror bias. Inadmissible evidence presented during a trial of a more-serious nature such as homicide or rape was less likely to cause bias during deliberation when jurors were told to strike the information from their memory. The effects were reversed when the offense was of a less-serious nature, such as vandalism or thievery. Participants had a more difficult time disregarding this evidence and thus gave bias verdicts (Rind et al., 1995).

Wissler and Saks (1985) completed a study in regards to the relation between previous actions and present offences. Participants were informed that the defendant on trial had a prior offense. There were three conditions: (1) the participants were informed of the similarity between the prior offense and the present crime, (2) the participants were informed of the dissimilar nature between the prior offense and the present crime, and (3) the participants were given no information about the previous offense. The participants were then given limiting instructions to only use the information presented about the defendant’s prior offense as a reference to the credibility of the defendant’s testimony. According to the results of the study, the introduction of the defendant’s prior criminal record did not have an influence on the defendant’s integrity; however, the type of prior offense did show an affect on credibility. If the prior transgression was similar in nature to the present crime, credibility was affected in such a way that more guilty verdicts were produced than if the prior conviction was dissimilar in nature (Wissler & Saks, 1985).

In my own experiment, I wished to discover if my fellow students, future jurors themselves, could succeed in disregarding information on command, much like the jurors are expected to do in a court case. I hypothesized that the students would be unable to objectively strike information from their memory and thus would give similar responses in the defense and defense stricken conditions.

Method

Participants

Seventy-one university students were conveniently sampled through an online experiment system. Participants were assigned to one of six different conditions based on severity of offense and whether the defense was present or stricken from the record. For the severe offense the no-defense condition had 10 participants, the defense-present condition had 14 participants and the defense-stricken condition had 13 participants. For the less severe offense the no-defense condition had 11 participants, the defense-present condition had 13 participants, and the defense-stricken condition had 10 participants For participation in this study, participants were given one point of extra credit towards one of their psychology classes. Participants were treated according to the APA code of ethics.

Materials and Procedures

The experiment was a 2 x 3 factorial design with 6 conditions. There were two independent variables; the type of crime, which was divided into two levels, rape and an honor board charge, and the type of defense, which was divided into three levels. These levels were no defense (the control group), the defense-presented group, and the defense-stricken group. The dependent variable was the degree of guilt. Each participant was given scenario in which the defendant was being charged with rape or was being brought up on Honor Board charges for plagiarism. Each participant was given exactly three minutes to read through the scenario in its entirety (See Appendix A). After the scenarios had been read thoroughly and collected, a Likert-style questionnaire was distributed (See Appendix B). This style of questioning gives a statement and has the participant rate on a scale, in this experiment one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree), how highly they agree or disagree with the statement. Of the 10 questions on this survey, 5 were distractor questions.

Results

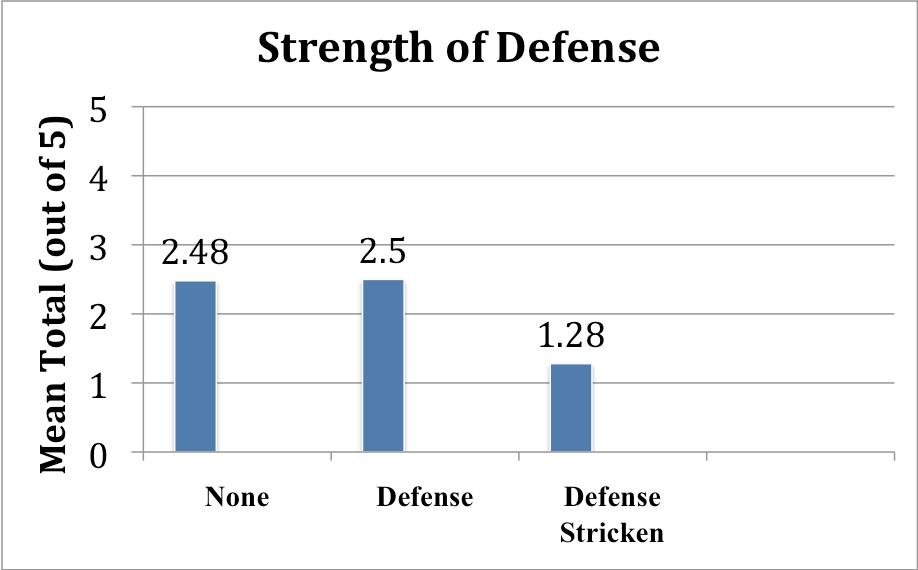

A 2 (type of crime) by 3 (type of defense) analysis of variance was used to analyze the results with post hoc analyses used as necessary. Of the five experimental questions, three produced significant results. For question one, The defendant had a strong defense, the defense-stricken condition produced significantly lower ratings than the other two conditions, F(2,64) = 3.75, p = .029 (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mean total of ratings for overall strength of defense.

Figure 1: Mean total of ratings for overall strength of defense.

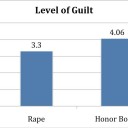

Question two, which looks closely at the guilt level of the defendant, was significantly higher in the honor board scenario than in the rape scenario, F(1,65) = 9.54, p = .003 (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Mean total of ratings of overall level of guilt for the type of crime.

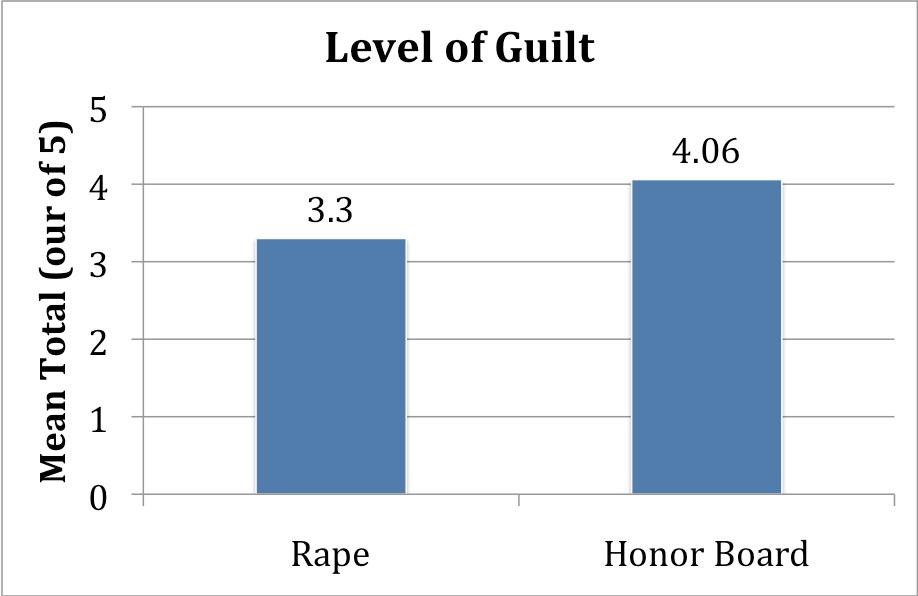

Question two also produced significant results across type of defense with the defense and defense-stricken conditions generating similar ratings while the control or no defense condition produced significantly lower ratings, F(2,65) = 3.44, p = .038 (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Mean total of ratings for overall level of guilt for the type of defense presented.

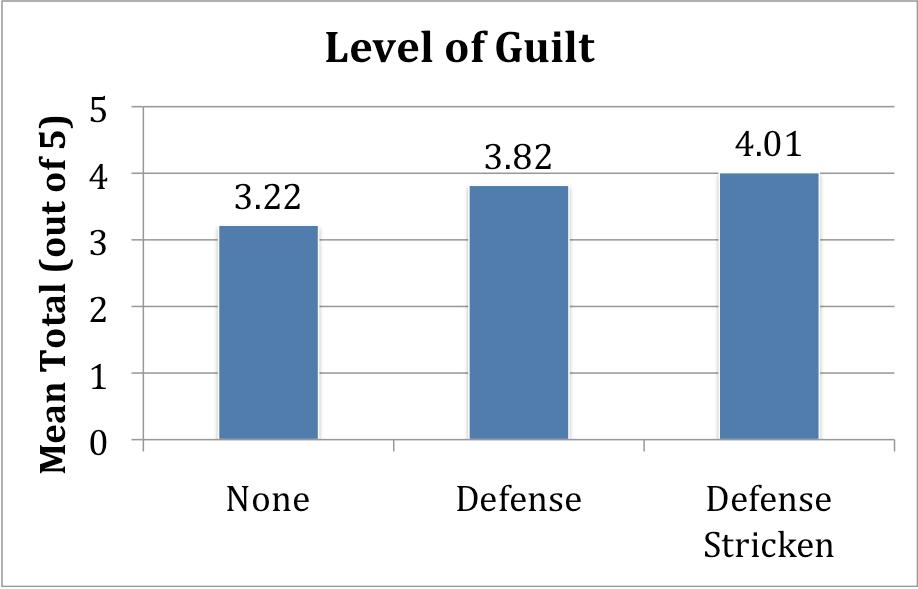

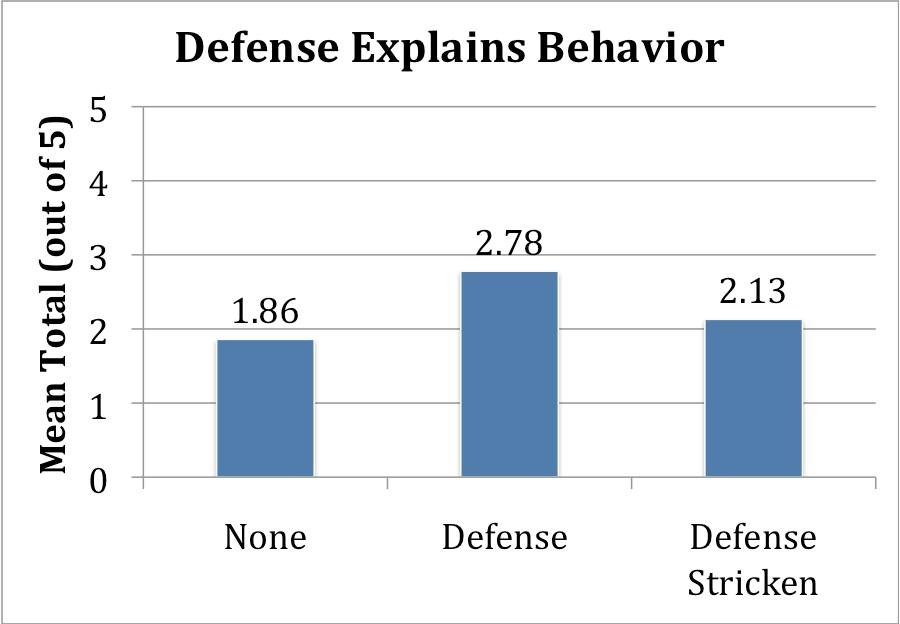

Finally, question three, which asked if the defense explains the defendant’s behavior once again produced similar results in the defense and defense stricken conditions with the control condition significantly lower than the other two conditions, F(2,66) = 5.12, p = .009 (See Figure 4).

Figure 4: Mean total of ratings for the belief that the defense presented in the scenario explained the defendant’s behavior.

Discussion

Of the five experimental questions, three questions produced statistically significant results. The first question focused on the strength of the defense. All participants believed the defendant to have a particularly weak defense, whether the defendant was being charged with rape or plagiarism and thus rated it low on the Likert scale with the defense-stricken group rating significantly lower than the other two defense conditions. These results supported the idea that none of the conditions believed the defendant had a particularly strong defense. The participants in the defense stricken-condition believed that in addition to the defendant not having a particularly strong defense, the defense was made even weaker when the prosecution supplied evidence for why it should be inadmissible. This was unexpected, for this condition rated the defense lower than the condition in which no defense was presented.

For the second question indicating the defendant was guilty, students rated the Honor Board (plagiarism) scenario as having a significantly higher level of guilt. This implies it may be easier for university students to relate to a student being brought up for an Honor Board violation in one of two ways; that the participant has committed this offense before and thus can empathize with the defendant, or that the crime is not perceived as a severe offense and thus does not need a strong defense.

The question of guilt also produced significant differences between the defense conditions with the defense and the defense stricken groups having similar ratings, both of which were significantly higher than the no defense group. It can be concluded that due to the similarities between the defense groups, the participants were unable to objectively strike the defense from their memory.

Finally, the last question stated that the defense explained the defendant’s behavior. Both defense conditions rated this statement higher and were significantly different from the no defense group, again indicating that they were not able to disregard the defense when the Judge had it stricken from the record. It was predicted that if the participants in the defense stricken condition were able to objectively disregard the defense, then they would have rated this question lower or would have given similar ratings as the no defense condition. In conclusion, it can be inferred from the results presented here that the participants were not able to follow the instructions to discount specific information regarding the defense presented in the scenarios.

References

Golding, J. M., & MacLeod, C. M. (1998). Instructions to disregard and the jury: Curative and paradoxical effects. Intentional forgetting: Interdisciplinary approaches. New Jersey: Lawrence Eribaum Associates Publishers.

Jonas, H., (2007). Why jurors do not disregard inadmissible evidence: Psychological reactance versus ironic process of mental control. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B. Sciences and Engineering, 68(01), 642.

Rind, B., Jaeger, M., & Strohmetz, D. B. (1995). The effect of crime seriousness on simulated jurors’ use of inadmissible evidence. The Journal of Social Psychology, 135(4), 417-424. Retrieved from http://pao.chadwyck.com/PDF/1310148991152.pdf

Sue, S., Smith R., & Caldwell, C. (1973). Effects of inadmissible evidence on the decisions of simulated jurors: A moral dilemma. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 3(4), 345-353. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1973.tb02401.x

Wissler, R. L., & Saks, M .J. (1985). On the inefficacy of limiting instructions. Law and Human Behavior, 9(1), 37-48. doi: 10.1007/BF01044288

Appendix A

Honor Board Scenario 1 (control)

Chairman of the Board: This is hearing case number 54255 on the date of September 7th. My name is William Davis and I am the chairperson and only non-voting member of the board. These are the rest of the board members.

The other seven members introduce themselves.

Chairman: I see that we have seven or more members present thus giving us a quorum. At this time do you have any questions on the objectivity of any of these board members?

Complainant: No sir.

Respondent: No sir.

Chairman: I will now read the charges against the respondent. Victor Lewis, you have been charged with Honor Code violation 2E, appropriating passages or ideas from another and using them as one’s own without proper documentation. On Honor Board, there are three pleas; Responsible, Not Responsible, and No Plea. No Plea meaning that at this time you do not wish to make a statement but would rather the board decide. Do you have any questions about the charges or the pleas?

Respondent: No sir.

Chairman: What is your plea?

Respondent: Not Responsible.

Honor Board Scenario 2

Chairman of the Board: This is hearing case number 54255 on the date of September 7th. My name is William Davis and I am the chairperson and only non-voting member of the board. These are the rest of the board members.

The other seven members introduce themselves.

Chairman: I see that we have seven or more members present thus giving us a quorum. At this time do you have any questions on the objectivity of any of these board members?

Complainant: No sir.

Respondent: No sir.

Chairman: I will now read the charges against the respondent. Victor Lewis, you have been charged with Honor Code violation 2E, appropriating passages or ideas from another and using them as one’s own without proper documentation. On Honor Board, there are three pleas; Responsible, Not Responsible, and No Plea. No Plea meaning that at this time you do not wish to make a statement but would rather the board decide. Do you have any questions about the charges or the pleas?

Respondent: No sir.

Chairman: What is your plea?

Respondent: Not Responsible. Until the moment my teacher pulled me aside after class, I was completely unaware of what plagiarism even was let alone that I had actually done it.

Honor Board Scenario 3

Chairman of the Board: This is hearing case number 54255 on the date of September 7th. My name is William Davis and I am the chairperson and only non-voting member of the board. These are the rest of the board members.

The other seven members introduce themselves.

Chairman: I see that we have seven or more members present thus giving us a quorum. At this time do you have any questions on the objectivity of any of these board members?

Complainant: No sir.

Respondent: No sir.

Chairman: I will now read the charges against the respondent. Victor Lewis, you have been charged with Honor Code violation 2E, appropriating passages or ideas from another and using them as one’s own without proper documentation. On Honor Board, there are three pleas; Responsible, Not Responsible, and No Plea. No Plea meaning that at this time you do not wish to make a statement but would rather the board decide. Do you have any questions about the charges or the pleas?

Respondent: No sir.

Chairman: What is your plea?

Respondent: Not Responsible. Until the moment my teacher pulled me aside after class, I was completely unaware of what plagiarism even was let alone that I had actually done it.

Chairman: I’m sorry, but every student was informed of what plagiarism is and how to avoid it at the beginning of their freshman year and every semester thereafter. I’m afraid we cannot accept that defense and I must ask the quorum to strike that from the record.

Rape Scenario 1 (Control)

From case number 54255: Victor Lewis vs. the State of California on the rape of Ashley Mitchell

Judge: Thank you, please be seated. Defense you may call your next witness.

Defense Attorney (DA): Thank you, Your Honor. The defense calls Victor Lewis back to the stand.

Defendant stands and walks to the stand.

Police Officer: Do you swear to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth so help you God?

Victor: Yes I do.

Defendant takes a seat.

DA: Would you please describe the night of September 7th, in your own words.

Victor: I had just finished grabbing a bite to eat at Zeke’s with a friend of mine when I received a phone call from Ashley to meet her at her apartment around 8:00 PM. When I arrived, I found her door slightly open. I found her in the bedroom. She was laying there crying.

DA: So when you arrived, the alleged crime had already been committed?

Victor: Yes ma’am, that is correct.

Rape Scenario 2

From case number 54255: Victor Lewis vs. the State of California on the rape of Ashley Mitchell

Judge: Thank you, please be seated. Defense you may call your next witness.

Defense Attorney (DA): Thank you, Your Honor. The defense calls Victor Lewis back to the stand.

Defendant stands and walks to the stand.

Police Officer: Do you swear to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth so help you God?

Victor: Yes I do.

Defendant takes a seat.

DA: Would you please describe the night of September 7th, in your own words.

Victor: I had just finished grabbing a bite to eat at Zeke’s with a friend of mine when I received a phone call from Ashley to meet her at her apartment around 8:00 PM. When I arrived, I found her door slightly open. I walked inside and found her in the bedroom. She came up to me, we started making out, and one thing led to another. The next thing I know we’re laying there and she is crying.

DA: So you can’t recall what happened between the time you got there until right after the act?

Victor: No ma’am.

DA: Have you ever heard of sex addiction, Mr. Lewis?

Victor: No ma’am.

DA: Sex addiction is a compulsive behavior that completely dominates the addict’s life. Sexual addicts make sex a priority more important than say family, friends, or work. Does any of this ring a bell or sound familiar?

Victor: Yes ma’am.

DA: I would like to enter into evidence the diagnosis of clinical psychologist, Dr. Nora Walker. It states that Mr. Lewis suffers from severe sexual addiction meaning that he cannot control his sexual urges.

Rape Scenario 3

From case number 54255: Victor Lewis vs. the State of California on the rape of Ashley Mitchell

Judge: Thank you, please be seated. Defense you may call your next witness.

Defense Attorney (DA): Thank you, Your Honor. The defense calls Victor Lewis back to the stand.

Defendant stands and walks to the stand.

Police Officer: Do you swear to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth so help you God?

Victor: Yes I do.

Defendant takes a seat.

DA: Would you please describe the night of September 7th, in your own words.

Victor: I had just finished grabbing a bite to eat at Zeke’s with a friend of mine when I received a phone call from Ashley to meet her at her apartment around 8:00 PM. When I arrived, I found her door slightly open. I walked inside and found her in the bedroom. She came up to me, we started making out, and one thing led to another. The next thing I know we’re laying there and she is crying.

DA: So you can’t recall what happened between the time you got there until right after the act?

Victor: No ma’am.

DA: Have you ever heard of sex addiction, Mr. Lewis?

Victor: No ma’am.

DA: Sex addiction is a compulsive behavior that completely dominates the addict’s life. Sexual addicts make sex a priority more important than say family, friends, or work. Does any of this ring a bell or sound familiar?

Victor: Yes ma’am.

DA: I would like to enter into evidence the diagnosis of clinical psychologist, Dr. Nora Walker. It states that Mr. Lewis suffers from severe sexual addiction meaning that he cannot control his sexual urges.

Prosecuting Attorney: Objection, Your Honor. Sexual Addiction is not a viable diagnosis for there is too little research saying whether it does in fact even exist. Without that research, we might as well allow him to draw a fictitious defense out of a magic hat.

Judge: I agree. Dr. Walker’s diagnosis will be dismissed from evidence and the jury will strike that last statement from the record. Please continue counselor.

Appendix B

Please answer the following questions based on the scenario you have just read. When you have finished, please sit quietly until everyone has finished and the experimenter comes by to collect the questionnaire.

Age: ___________

Sex: M F

Year in School: Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior

1) What day was the Honor Board Hearing:

a. September 17th

b. September 23rd

c. September 7th

d. September 1st.

2) The respondent, Victor Lewis, had a strong defense.

1———————-2———————-3———————-4———————-5

Strongly Disagree Neutral Strongly Agree

3) The quorum is made up of __ members:

a. 8

b. 6

c. 9

d. 7

4) The respondent, Victor Lewis, is responsible.

1———————-2———————-3———————-4———————-5

Strongly Disagree Neutral Strongly Agree

5) What Honor Code violation was the respondent being charged with:

a. 8A

b. 2E

c. 4C

d. 3B

6) His sentencing should be severe.

1———————-2———————-3———————-4———————-5

Strongly Disagree Neutral Strongly Agree

7) What is the case number for this hearing?

a. 54255

b. 52341

c. 63421

d. 32980

8) Victor Lewis’s defense explains his behavior.

1———————-2———————-3———————-4———————-5

Strongly Disagree Neutral Strongly Agree

9) Was the Chairman a male or a female”

a. Male

b. Female

c. I don’t know

10) Due to mitigating circumstances, the defendant should have a light sentence.

1———————-2———————-3———————-4———————-5

Strongly Disagree Neutral Strongly Agree