I commented on Brittany and Danielle’s blogs.

Seeing the American Shakespeare Center’s performance of Romeo and Juliet helped me to view the play in a completely different way. Although I have read Romeo and Juliet, I had never actually seen Romeo and Juliet performed before. Throughout high school, my teachers either randomly assigned parts for us to read out loud in class, or had us read plays for homework and then discuss them in class. I did not realize how much I was missing out on until I started to see performances of plays that I had read. It is incredibly difficult to visualize the characters and their actions to move beyond thinking about the plot in this type of environment, which makes me grateful to have discovered the vast amount of resources and lessons in existence already to avoid this type of boring, one-dimensional exposure to Shakespeare because his plays are really very multifaceted.

The American Shakespeare Center’s performance really brought the characters to life for me. It was a lot easier to keep up with who was a Montague and who was a Capulet because they wore different colors to help differentiate which family they belong to. The actors also really made the character’s personalities shine through. This was true for Mercutio in particular. When I read the play in class, I do not remember him being such a funny character, and frankly, I did remember anything about him other than Tybalt killing him; however, the man who played him stole the show. The actor clearly seemed invested in his role and comfortable with putting himself out there to elicit laughs from the audience so that Mercutio was brought to the forefront as one of the most memorable and likeable characters. This particular performance also gave a sense of what it would have been like to see the play performed in Shakespeare’s time. The props and scenery was pretty minimalistic for a performance of this caliber and the background stayed the same throughout the entirety of the play. Additionally, the lights stayed on for the entire play, and there were no special effects done through lighting. These factors helped me to visualize how plays were performed in Shakespeare’s day more than I would have gotten from just hearing what it was like.

One of my favorite ideas from The American Shakespeare Center Study Guide for Romeo and Juliet is called Choice, which is an assignment where the teacher “asks students and performers to consider the different choices they might make, given the clues within the text” (American Shakespeare Center p. 26). I envision this activity coming to life in a classroom by having students work in groups to determine how a scene should be acted out. One of the great things about Shakespearean plays is that they encompass so many different concepts from action to romance, so students will likely be able to choose a scene that is appealing to their own interests. Students can each pick a character to bring to life from that scene and think about things such as the vocal inflections in what they are saying, the emotions they are conveying, and the physical movements that go along with the words. It is so easy to get lost in the basic plot of a Shakespearean play just reading it straight through, but activities like this require students to think deeper about the nuances of each character and what the words on the page really mean. Many students dread Shakespeare, but perhaps being able to invest their time into a scene and character they find interesting will alleviate some of the stigma attached to Shakespeare because it allows students to focus on the parts of the plays they do enjoy.

Another activity that American Shakespeare Center suggests is called Iambic Bodies, which involves “Ask[ing] volunteers to line up in front of the classroom, with a chair behind each one. You may wish to couple up your iambs by placing their chairs close together, then a space, then the next two chairs” (American Shakespeare Center p. 31). The idea behind this is that the students who are standing read the stressed syllables and the students who are sitting read the unstressed syllables to get a better sense of iambic pentameter. Personally, I did not actually understand what iambic pentameter was until doing activities like this one in college. I could easily rattle off the definition that I had memorized, but I had no clue what it actually meant conceptually. Demonstrations like this are incredibly important because Shakespearean language is tough this opens up the opportunity to not only discuss iambic pentameter, but also other unique qualities that appear in Shakespearean language. High school students generally are not familiar with words like “o’er” or that Shakespeare uses them to conform to iambic pentameter, and this is the perfect opportunity to explain that. Another technique that could be incorporated into an activity like this is having students read the lines in high pitched or low pitched voices. It’s hard to get used to Shakespearean language, and this technique makes everyone sound silly, so readers who struggle with the new language or reading in general have time to adjust to the new way of talking without feeling embarrassed because their struggling is obvious.

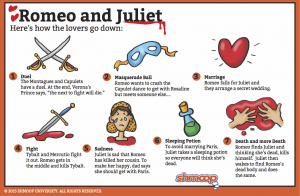

In my classroom, I want students to view Shakespeare as an author who is accessible and fun to read, rather than tedious and unpleasant. It’s important to remember that these texts were meant to be performed and students are not going to get the full experience of reading Shakespeare without either seeing a performance or doing performance-based activities to bring the characters to life. As exemplified by the image above, the plot of Romeo and Juliet is actually quite simple. There is so much more to be gained from Shakespeare that extends beyond focusing on just the plot, I plan to use class time going further in depth into characterizations, themes, and performance qualities of the text, rather than reading the entire play just to be able to produce a basic summary of the plot.

Has anybody shopped at All Day Vape? xx

sup

Has anybody shopped at Pipe Dreams UK? xx

Has anyone ever shopped at Acushnet Vapor Co? 🙂

Has anyone ever been to The Vapor Island? 🙂

Has anybody visited Vapure Kearny Mesa? 🙂

Romeo and Juliet is the most famous love story in the English literary tradition. Love is naturally the play’s dominant and most important theme. The play focuses on romantic love, specifically the intense passion that springs up at first sight between Romeo and Juliet. In Romeo and Juliet, love is a violent, ecstatic, overpowering force that supersedes all other values, loyalties, and emotions. In the course of the play, the young lovers are driven to defy their entire social world: families (“Deny thy father and refuse thy name,” Juliet asks, “Or if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love, / And I’ll no longer be a Capulet”); friends (Romeo abandons Mercutio and Benvolio after the feast in order to go to Juliet’s garden); and ruler (Romeo returns to Verona for Juliet’s sake after being exiled by the Prince on pain of death in II.i.76–78). Love is the overriding theme of the play, but a reader should always remember that Shakespeare is uninterested in portraying a prettied-up, dainty version of the emotion, the kind that bad poets write about, and whose bad poetry Romeo reads while pining for Rosaline. Love in Romeo and Juliet is a brutal, powerful emotion that captures individuals and catapults them against their world, and, at times, against themselves.

The powerful nature of love can be seen in the way it is described, or, more accurately, the way descriptions of it so consistently fail to capture its entirety. At times love is described in the terms of religion, as in the fourteen lines when Romeo and Juliet first meet. At others it is described as a sort of magic: “Alike bewitchèd by the charm of looks” (II.Prologue.6). Juliet, perhaps, most perfectly describes her love for Romeo by refusing to describe it: “But my true love is grown to such excess / I cannot sum up some of half my wealth” (III.i.33–34). Love, in other words, resists any single metaphor because it is too powerful to be so easily contained or understood.

Romeo and Juliet does not make a specific moral statement about the relationships between love and society, religion, and family; rather, it portrays the chaos and passion of being in love, combining images of love, violence, death, religion, and family in an impressionistic rush leading to the play’s tragic conclusion.

Love as a Cause of Violence

The themes of death and violence permeate Romeo and Juliet, and they are always connected to passion, whether that passion is love or hate. The connection between hate, violence, and death seems obvious. But the connection between love and violence requires further investigation.

Love, in Romeo and Juliet, is a grand passion, and as such it is blinding; it can overwhelm a person as powerfully and completely as hate can. The passionate love between Romeo and Juliet is linked from the moment of its inception with death: Tybalt notices that Romeo has crashed the feast and determines to kill him just as Romeo catches sight of Juliet and falls instantly in love with her. From that point on, love seems to push the lovers closer to love and violence, not farther from it. Romeo and Juliet are plagued with thoughts of suicide, and a willingness to experience it: in Act III, scene iii, Romeo brandishes a knife in Friar Lawrence’s cell and threatens to kill himself after he has been banished from Verona and his love. Juliet also pulls a knife in order to take her own life in Friar Lawrence’s presence just three scenes later. After Capulet decides that Juliet will marry Paris, Juliet says, “If all else fail, myself have power to die” (III.v.242). Finally, each imagines that the other looks dead the morning after their first, and only, sexual experience (“Methinks I see thee,” Juliet says, “. . . as one dead in the bottom of a tomb” (III.v.242; III.v.55–56). This theme continues until its inevitable conclusion: double suicide. This tragic choice is the highest, most potent expression of love that Romeo and Juliet can make. It is only through death that they can preserve their love, and their love is so profound that they are willing to end their lives in its defense. In the play, love emerges as an amoral thing, leading as much to destruction as to happiness. But in its extreme passion, the love that Romeo and Juliet experience also appears so exquisitely beautiful that few would want, or be able, to resist its power.

The Individual Versus Society

Much of Romeo and Juliet involves the lovers’ struggles against public and social institutions that either explicitly or implicitly oppose the existence of their love. Such structures range from the concrete to the abstract: families and the placement of familial power in the father; law and the desire for public order; religion; and the social importance placed on masculine honor. These institutions often come into conflict with each other. The importance of honor, for example, time and again results in brawls that disturb the public peace.

Though they do not always work in concert, each of these societal institutions in some way present obstacles for Romeo and Juliet. The enmity between their families, coupled with the emphasis placed on loyalty and honor to kin, combine to create a profound conflict for Romeo and Juliet, who must rebel against their heritages. Further, the patriarchal power structure inherent in Renaissance families, wherein the father controls the action of all other family members, particularly women, places Juliet in an extremely vulnerable position. Her heart, in her family’s mind, is not hers to give. The law and the emphasis on social civility demands terms of conduct with which the blind passion of love cannot comply. Religion similarly demands priorities that Romeo and Juliet cannot abide by because of the intensity of their love. Though in most situations the lovers uphold the traditions of Christianity (they wait to marry before consummating their love), their love is so powerful that they begin to think of each other in blasphemous terms. For example, Juliet calls Romeo “the god of my idolatry,” elevating Romeo to level of God (II.i.156). The couple’s final act of suicide is likewise un-Christian. The maintenance of masculine honor forces Romeo to commit actions he would prefer to avoid. But the social emphasis placed on masculine honor is so profound that Romeo cannot simply ignore them.

It is possible to see Romeo and Juliet as a battle between the responsibilities and actions demanded by social institutions and those demanded by the private desires of the individual. Romeo and Juliet’s appreciation of night, with its darkness and privacy, and their renunciation of their names, with its attendant loss of obligation, make sense in the context of individuals who wish to escape the public world. But the lovers cannot stop the night from becoming day. And Romeo cannot cease being a Montague simply because he wants to; the rest of the world will not let him. The lovers’ suicides can be understood as the ultimate night, the ultimate privacy.

The Inevitability of Fate

In its first address to the audience, the Chorus states that Romeo and Juliet are “star-crossed”—that is to say that fate (a power often vested in the movements of the stars) controls them (Prologue.6). This sense of fate permeates the play, and not just for the audience. The characters also are quite aware of it: Romeo and Juliet constantly see omens. When Romeo believes that Juliet is dead, he cries out, “Then I defy you, stars,” completing the idea that the love between Romeo and Juliet is in opposition to the decrees of destiny (V.i.24). Of course, Romeo’s defiance itself plays into the hands of fate, and his determination to spend eternity with Juliet results in their deaths. The mechanism of fate works in all of the events surrounding the lovers: the feud between their families (it is worth noting that this hatred is never explained; rather, the reader must accept it as an undeniable aspect of the world of the play); the horrible series of accidents that ruin Friar Lawrence’s seemingly well-intentioned plans at the end of the play; and the tragic timing of Romeo’s suicide and Juliet’s awakening. These events are not mere coincidences, but rather manifestations of fate that help bring about the unavoidable outcome of the young lovers’ deaths.

The concept of fate described above is the most commonly accepted interpretation. There are other possible readings of fate in the play: as a force determined by the powerful social institutions that influence Romeo and Juliet’s choices, as well as fate as a force that emerges from Romeo and Juliet’s very personalities chec khttps://freebooksummary.com/romeo-juliet-is-love-stronger-than-hate-85449

Courtney, you said exactly what I was thinking. When I was in high school we had the same assignments for reading Shakespeare. I felt so caught up in the play and I was actually getting the jokes when I saw it performed! Any high school student would love all the funny bits in the ASC performance. I think showing a live play would be essential to a Shakespeare unit!