Abstract

Parental involvement is oftentimes neglected in families. For many parents, lack of time and stressors in their personal lives interfere with their ability to be engaged with their children as much as they should be. However, for some families, economic status becomes an additional prominent factor in their lack of ability to be involved. The purpose of this study is to investigate the differences of family involvement for families of different economic statuses. Ninety-nine families were studied with 78 children from Head Start, a federally subsidized preschool for families with economic need, across three counties in Virginia. The remaining 21 children were from the Andy Taylor Center, a preschool that families apply and pay for to attend, which is located on campus at Longwood University. After having received Family Fun Time activities the week prior, families received a questionnaire that addresses demographic information, enjoyment of activities, amount of family involvement, and completion. This is a mixed methods study with quantitative analysis being derived from the close-ended questions pertaining to family involvement and annual household income. Qualitative data was collected from the open-ended questions on the questionnaire of what the families enjoyed about the activities and why, what their child learned from the activities, and recommendations for the activities. It was predicted that the statistical results will reveal that the lesser the annual household income, the lesser the amount of family involvement. Common themes that appeared were child growth or learning, simplicity of the activities, and quality time with family.

Introduction

A common misconception within families is that education is strictly left up to the schools and hired educators. However, research indicates that children are much more successful when parents are involved at home (Prins & Toso, 2008). The involvement can come in several forms from directly helping the child with their schoolwork, exchanging information about what they are learning and how they’re learning it, being involved with the school or staff, or engaging with them through non-educational activities. However, many research studies fail to consider the barriers of socioeconomic status or social class in achieving the multiple forms of involvement. Socioeconomic status creates limitations for parents to be engaged in their child’s schoolwork, involved with the school through volunteering or parent-teacher meetings, and engaging in activities designated for family time (Ansari & Gershoff, 2016). This may be due to long hours spent working to provide for their family, family conflict of divorced parents or different guardians, and stress from social pressures. The stress placed on parents may lead to a lack of interaction with their children, including keeping them on track in school. Once children fall behind in school, it becomes a battle to bring the child back up, oftentimes leaving them behind throughout their education (Ansari & Gershoff, 2016). This study may provide a consideration for further researchers when evaluating family involvement by considering the struggles of families of low economic status. By examining levels of family engagement in relation to different socioeconomic statuses, as well as the effects of family involvement, conclusions about action plans to ensure educational success for students, no matter the background, can be made to educate both families and educational systems.

Literature Review

The term parental involvement is very broad in the characterization of a parent’s role in a child’s life, however, it is certain that having some sort of presence in a child’s life is essential. Ways to operationally define parental involvement are debated over, it was found that there was little agreement on how to conceptualize parental involvement (Gross et. al., 2019). Gross et al. (2019) evaluated this by examining the conceptual viewpoints of parental involvement of parents, teachers, early childhood staff, district leaders, and community leaders. In an educational approach, parents, teachers, and early childhood staff viewed involved parenting as ensuring that the child is at school on time or taking the time to know what the child is learning about in school; taking a further step would be helping the child with their schoolwork and even further would be being involved with the school itself through parent-teacher conferences or volunteering (Gross, et. al., 2019). Gross’ et al. (2019) most valuable findings combined conceptualized parent involvement as communication between the parent and child, parent involvement with the child’s school and social life, and collaborating with the community that the child is involved in.

A flawed, due to neglect of consideration for culturally diverse families, but formalized instrument that outlines the ideal parent and their engagement in a child’s education exists as the Parent Education Profile. The profile is essentially a guide to parenting and the expected roles and behaviors of parents in their children’s lives, specifically in education (Prins & Toso, 2008). Prins and Toso (2008) argue that to ensure the involvement of parenting in education, the PEP should be mandated where parents will be ranked upon a performance indicator, creating essentially a universal parenting guide to educational success for children (Prins and Toso, 2008). However, Prins and Torso (2008) argue that factors such as culture, socioeconomic status, and community play a role in the determinants of engagement within the family which is not taken into consideration with the PEP as the profile is centered around middle-class, predominately white parents. For children of disadvantaged families, such as low-income Latino families, many can fall behind in their reading, writing, and mathematics (Coba-Rodriguez et al., 2020). For example, at the beginning of schooling only 15% of Latino children can recognize letters while 36% of White children can (Coba-Rodriguez et al., 2020). The PEP would argue that the reason for these children being behind are that the parents are not involved in their children’s schooling, rather than taking into consideration the cultural diversity and additional barriers for disadvantaged families (Coba-Rodriguez et al., 2020). Kulic et al. (2019) was concerned with this achievement gap, stating that inequality is rooted in children from the beginning of schooling. Research shows that socioeconomic gaps early on in schooling with reading and math skills can almost predict future patterns of educational achievement or lack thereof (Kulic et al., 2019). With this evidence, the gap between these skills of wealthier families and low-income families is shown to progress through elementary, middle, and high school (Kulic et al., 2019).

By families acknowledging that education is not strictly left up to school systems and education institutions branching out to families for engagement with their child, the two can harmonize (Epstein, 2010). In a previously done study with Head Start, a program for income-eligible families, by Ansari and Gershoff (2016), it’s found that children learn best when they receive reinforcement at home rather than leaving the schooling strictly to the schools. With this, by educating parents through the Head Start program, the gap between parent involvement of wealthier families versus low-income families can narrow. The involvement of low-income families in their children’s preschool and kindergarten schooling has shown to produce improved reading abilities, lower rates of repeating a grade, and fewer children having to be placed in special education classes (Morrison et al., 2011. In Morrison’s et al. (2011) examination, they also advocate for Epstein’s model of parenting for a stronger relationship between the parent and child leading to enhanced cognitive abilities, positive emotional development, and good behavior of the child (Morrison et al., 2011). Epstein (2010) outlines several different practices that can be implemented by the school or family for each involvement; for example, families participate in student goal setting each year or a send home schedule of what the students are learning in class as a part of learning at home (Epstein, 2010). However, Epstein (2010) refutes her own practices by expressing challenges of involvement such as ensuring all information is communicated to families, taking into consideration language barriers, clear channels to home, etc. (Epstein, 2010).

The implementation of plans to create more parent engagement takes time and money that some institutions do not have. Epstein has carried out several family engagement projects in school systems; schools have shown to have taken a minimum time of three years for the creation of an action team, completion of activities, and to implement the work into the school’s and home’s structure (Epstein, 2010). Epstein (2010) considers the extension of learning from school to home and the reinforcement of parents and teachers as supporters as critical for student’s educational success. The vast amount of research on the roles of parents in student’s education all indicate the crucial need for family involvement. Although, the socioeconomic status of families that lead to limitations in family engagement and parent-child activities must be considered. With this, by working with Head Start in a lower income area, influencing and implementing family involvement in low socioeconomic families can help narrow the educational gap between students of wealthier families versus low-income families. Further research may consider studying race or culture in accordance with family engagement and student success.

Data and Methodology

Instrument

A survey questionnaire was created by the 50 members of the Social Research and Program Evaluation class at Longwood University. The survey asked both open and close ended questions. Items on the survey were designed to evaluate SMART objectives of each of the five activities that were completed the previous week by Head Start families. Items were included that also addressed demographic information, enjoyment of activities, amount of family involvement, and completion. Hard copies of the questionnaire were delivered to Head Start and the Andy Taylor Center.

Sample

The non-probability sample for this study was based on 99 children (ages three to five). Seventy-eight children attend Head Start in three counties in Virginia. Head Start is a federally subsidized preschool for families with economic need. Twenty-one children attend the Andy Taylor Center which is located on campus at Longwood University, and families apply and pay for their children to attend. Attached to the questionnaire was a children’s book to incentivize families to return the survey. Guardians of the children were asked to complete the survey and return it to the preschool the following school day. Teachers then sent a reminder home with children to return any outstanding questionnaires. This resulted in 20 questionnaires being returned. Overall, there was a 19.8% response rate.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis of the returned surveys was based on the close-ended questions. For this study, the dependent variable is parental involvement. The item from the questionnaire that was used to operationalize this was “How involved was your family throughout the activity?” The answer choices for this item were “Scale 0-10; 0 = not at all, 10 = a great amount,” in which families would circle the number. For this study, the dependent variable is socioeconomic status. The item from the questionnaire that was used to operationalize this was, “What is your annual household income?” The answer choices for this item were comprised of tax brackets, “1. Less than $10,000, 2. $10,000-$30,999, 3. $31,000-$50,999, 4. $51,000-$70,999, 5. $71,000-$90,999, 6. $91,000 or more, and 7. Prefer not to answer.” Descriptive statistics were used to analyze these variables.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis of the returned surveys was based on the open-ended questions. The open-ended questions on the survey were, “What did your family enjoy most about these activities? Why?”, “What did your child learn from these activities?”, and “What recommendations would you suggest to make these activities better?” To answer the research question, “How does socioeconomic status affect family involvement?”, inductive open coding was used to determine reoccurring themes in the respondent’s responses.

Findings

Quantitative Findings

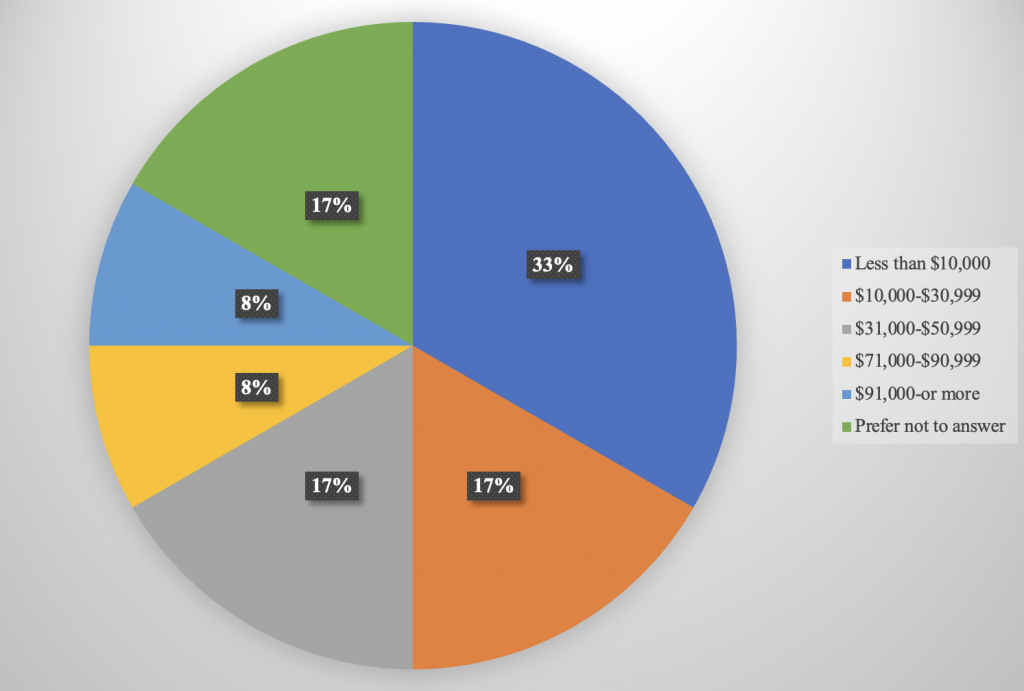

The dependent variable in this project is family involvement. This was measured by the question, “How involved was your family throughout the activity?” and coded on a scale 0, not at all, to 10, a great amount. The mean for this response was 9.14. The standard deviation for this response is 1.23. The independent variable in this project is socioeconomic status. This was measured by a question pertaining to annual household income and coded by answer choices with tax brackets of less than $10,000, $10,000-$30,999, $31,000-$50,999, $51,000-$70,999, $71,000-$90,999, $91,000 or more, and prefer not to answer. Only 16 surveys were analyzed for our quantitative findings as three surveys were returned after the analysis. Four people (33%) answered less than $10,000, two people (17%) recorded $10,000-$30,999, two people (17%) make $31,000-$50,999, zero surveyors claimed to make $51,000-$70,999, one person (8%) makes $71,000-$90,999, one person (8%) makes $91,000 or more, and two people (17%) preferred not to answer. See Figure 1 for chart. In a bivariate analysis of this activity, the annual household income is inconsistent with family involvement. Individuals who make less than $10,000 annually had a mean involvement of 9.25 out of 10. People who make $10,000-$30,999 annually had a mean involvement of 9.50. People who make $31,000-$50,999 annually had a mean involvement of 8.50. Those who make $71,000-$90,999 annually had a mean involvement of 10. Individuals who make $91,000 or more annually also had a mean involvement of 10. Lastly, individuals who preferred not to provide their annual household income had a mean involvement of 9 out of 10. It appears that the annual household income of families is inconsistent with their ratings of family involvement throughout the activities. The greatest amount of family involvement was within the two highest income brackets of $71,000-$90,999 and $91,000 or more, however, the data is still inconsistent considering the fluctuation of family involvement for brackets below $71,000.

Qualitative Findings

Three common concepts appeared across the open-ended questions in the 16 surveys received: growth, simplicity, and family time. Only 16 surveys were analyzed for our qualitative findings as three surveys were returned after the analysis. Words of growth appeared 13 times across the 16 surveys. For example, in survey seven, the parent answered, “My child learned how to be creative,” indicating skills that were unlocked while completing these Family Fun Time activities. Many other surveys also demonstrated that their child showed development, such as in survey one stating, “Listening to and following instructions and practiced counting,” and in surveys eight, nine, 10, and 11, the parents wrote about how their child recognized different shapes, letters, numbers, and colors. The Family Fun Time activities produced not only family time, but children the opportunity to learn valuable lessons. For example, in survey 15, the parent answered, “Patience not giving up if something doesn’t go her way or look how she expected it to.” Also, in survey 14, the parents said, “helps the child understand emotions without sounds and it helps them know the meaning of emotions,” demonstrating growth.

Six out of the 16 surveys contained words about the simplicity of the activities. In surveys three and 16, they mentioned how easy the activities were saying, “Our family really enjoyed how simple the activities were,” and “Also how easy the directions were.” In survey six, the parent thought the activities were too simple writing, “Make some of the activities harder.” In surveys 11 and 13, they appreciated the simplicity of the activities for the families and children and complimented how well planned out the activities were. In survey one, the parent sums up the simplicity of the activities for families to enjoy stating, “A free convenient activity to do as a family that’s prepackaged and easy to follow instructions.”

Family time was mentioned in 10 out of the 16 surveys received. The word ‘together’ appeared in six out of the 10 surveys mentioning family time whether it be completing the activities together as the respondent in survey seven says, “We enjoyed putting all different shapes together on the pizza survey” or the time together spent doing the activities such as the parent in survey four answered, “Time spent together, the talks, learning.” Families found the activities a great way to give their child something to do while also spending valuable family time. Such as in survey three, “and how much our child enjoyed them, even completing some with siblings” and in survey two, “helps on weekends giving them something to do.” Parents found these activities educational while also getting to spend time together as a family as a parent answered in survey 15 saying, “Spending time together doing something educational is always fun. “Family Time”.” The respondent in survey five also felt these activities to be beneficial for their child and their family as they said, “It’s fun when you want to do something fun and enjoyable for kids and family. It can be a learning skill, but fun for the kids.”

Conclusion

The aim of this research study was to examine levels of family involvement across the 19 surveys returned in correlation to different survey questions that were used as independent variables, one being the close-ended question pertaining to annual household income. A bivariate analysis revealed that annual household income was inconsistent with family involvement ratings. However, it is significant to note that the highest ratings of family involvement were families of tax brackets $71,000-$90,999 and $91,000 or more, but ratings fluctuated for tax brackets below $71,000. The qualitative analysis of the open-ended questions on the survey revealed three common themes of growth, simplicity, and family time across the 16 survey responses analyzed. The results of this study do not provide solid evidence that socioeconomic status of families have a significant effect on family involvement. However, the insignificant results may be due to the low response rate of families from Head Start and Andy Taylor. This study is still crucial for families, educational institutions, and researchers to consider because of the barriers socioeconomic status poses for families. While prior research does emphasize the importance of family engagement in student success, much of the research fails to include the comparison of family involvement of families of high and low socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic status impedes families to provide for and be as engaged with their children compared to families of higher socioeconomic status. Encouraging family time and parent engagement through at-home activities or inspirational messages from school systems in low-income areas may spark parents to become more involved with their child’s schoolwork and social life, narrowing the gap between educational success for families of different socioeconomic statuses.

Figure 1

Annual Household Income of Survey Respondents

References

Ansari, A., & Gershoff, E. (2015). Parent involvement in head start and children’s development: Indirect effects through parenting. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(2), 562–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12266

Coba-Rodriguez, S., Cambray-Engstrom, E., & Jarrett, R. L. (2020). The home-based involvement experiences of low-income Latino families with preschoolers transitioning to kindergarten: Qualitative findings. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(10), 2678–2696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01781-7

Epstein, J. L. (2010). School/Family/Community Partnerships: Caring for the children we share. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(3), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171009200326

Epstein, J. L., et al. (2019). School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action. Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Gross, D., Bettencourt, A. F., Taylor, K., Francis, L., Bower, K., & Singleton, D. L. (2019). What is parent engagement in early learning? depends who you ask. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(3), 747–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01680-6

Kulic, N., Skopek, J., Triventi, M., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (2019). Social background and children’s cognitive skills: The role of Early Childhood Education and care in a cross-national perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 45(1), 557–579. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073018-022401

Morrison, J. W., Storey, P., & Zhang, C. (2011). Accessible Family Involvement in Early Childhood Programs. Dimensions of Early Childhood, 39(3), 21–26.

Prins, E., & Toso, B. W. (2008). Defining and measuring parenting for Educational Success: A critical discourse analysis of the parent education profile. American Educational Research Journal, 45(3), 555–596. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831208316205