Abstract

When it comes to the success children have in school and in life, parental involvement has a huge factor. The purpose of this study was to see how take home activities can affect parent involvement within the Head Start program. Head Start is a federal program that promotes school readiness for preschool aged children who are in low-income families (The Administration for Children and Families, 2020). This was a mixed methods study and activities were sent home for 51 Head Start children and their families to complete. After completion they filled out a survey and sent them in. Eleven surveys were returned which showed an overwhelming response of family interaction and engagement as well as expressing having fun and enjoyment. The study found that parents who were rarely to attend Head Start programs were more inclined to assist their children with the activities.

Parental Involvement at Home Effects on Parental Involvement in Education

In this study we looked into finding the amount of involvement with children at home with their parents, grandparents, or other parental guardians. The research question focused on in the study was: Can take-home activities encourage and stimulate parental and family involvement? The original hypothesis was that the more involvement a parent or parental figure made at home with the children, the more inclined they would be to participate or volunteer with activity and programs at Head Start.

Previous research has shown that the best time for parents or guardians to get more involved with their child/children at school is during their younger ages (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011). Looking at previous research, we hypothesized that the more involvement parents or guardians have at home with their children, the more interaction they will have in the schools/Head Start program.

Some deficiencies and limitations that were found in previous research are all in one small specific location, which was then generalized for around the United States. Some studies only focused on two or three schools. The studies should be used to see how willing a parent or guardian is to get involved by sending challenging activities(El Nokail, Bachman, & Votruba-Drzal, 2010).

Literature Review

Parental Involvement

Parental involvement is a way for parents to improve their children’s success in school with grades, attendance, and participation, as well as out-of-school with attitudes and expectations of the public. If a parent is more involved with their child, they will have greater success within their academic careers and their professional careers later in life (Khajehpour & Ghazvini, 2011; Smith, Wohlstetter, Kuzin, & Pedro, 2011; Bower & Griffin, 2011).

How Parents Are Involved

The main time parents can be more involved with their children is when they are in the earlier educational stages of life. This is partly due to younger children being more open about their parents attending school functions, events, field trips, and volunteering in classrooms than older children (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011). At this age, parents can get involved by monitoring and assisting with homework, having and developing frequent communication with teachers, attending school-run events, or getting involved with the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA), to become more involved with the school setting (Ansari & Gershoff, 2015; El Nokail, Bachman, & Votruba-Drzal, 2010). Along with academics, parents can also get involved in activities such as plays and performances or taking a role on an athletic team at the school (Bower & Griffin, 2011).

According to Epstein’s Model of School, Family, and Community Partnerships, there are six different types of being involved as a parent. Type one is the basic obligations of families, which is providing the basic needs for health and safety. The second type is the basic obligations of the school, which is being involved in phone calls, report cards and parent-teacher conferences. Type three is being involved at school by volunteering in the classrooms or attending field trips. The fourth one involves learning activities in the household like assisting the child with homework. Type five is involved in decision-making, governance, and advocacy by serving in leadership positions like the PTA. The last type is collaboration and exchanges within community organizations by participating in after-school programs and using health resources (Epstein & Dauber, 1991, as seen in Smith, Wohlstetter, Kuzin, & Pedro, 2011, p. 78).

Head Start

Parent involvement can be difficult. This is where the Head Start program can help assist families. The program works with low-income families and provides an education for children and gets the parents or a parental figure involved in an activity to help gain more skills (Ansari & Gershoff, 2015; Zigler & Muenchow, 1992). On average, children first join the Head Start program at 40.83 months and the average age of the parents is 28.5. The program consists mainly of minorities and majority of the children are from a single-parent household (Ansari & Gershoff, 2015).

Limitations

One of the biggest limitations in the articles is the number of children and parents the information and statistics were from. The studies weren’t completed with a wide range of families from different areas, and were mostly completed with families who are from one or two different schools. This made it so families from one area generalized the entire public from the study. Families come from a wide range of backgrounds from socioeconomic status to race and ethnicity, and if this is just one area, there is no way to find out how different these numbers will be for people around the world. (Smith, Wohlstetter, Kuzin, & Pedro, 2011; Bower & Griffin, 2011). A second limitation is there should be more challenging activities sent home, so parents aren’t ‘casually’ going through the project just to get it done. These studies should be used to see how much the parent is willing and wanting to get involved, so the more challenging, the more reliable and interesting the information received will be (El Nokail, Bachman, & Votruba-Drzal, 2010).

Data & Methods

Instrument

A survey questionnaire was created by the 40 members of the Social Research and Program Evaluation team at Longwood University. The survey contained both open-ended and closed-ended questions. Items on the survey were designed to evaluate SMART objectives of each of five activities that were completed the previous week by Head Start families. Beyond the objectives of the activities, participants were asked about their experiences with Head Start, take home activities, and demographic information about their households.

Sample

The non-probability sample for this study was based on the 51 children (ages three to five) who attend Head Start in two rural counties in Virginia. After activities were sent home with children for five days, the questionnaire was sent home with all 51 students. Attached to the questionnaire was a children’s book, to incentivize families to return the survey. Guardians of the children were asked to complete the survey and return it to the Head Start teacher the following school day. 11 questionnaires were returned the next school day. Teachers then sent a reminder home with children to return any outstanding questionnaires. This resulted in 0 more questionnaires being returned. Overall, there was a 22% response rate.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis of the returned surveys is based on the close-ended questions. For this study the dependent variable is parental involvement. The item from the questionnaire that was used to operationalize this was, “How much did you assist your child in this activity?” The answer choices for this item was a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being not assisting at all and 10 being a great amount of assistance. The independent variable for this study is parental participation at Head Start. The item from the questionnaire that was used to operationalize this was, “How often do you attend programs at Head Start?” The answer choices for this question were: often, sometimes, rarely and never. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze these variables.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis of the returned surveys is based on the open-ended questions. The open-ended questions on the survey were: “What did your family enjoy most about these activities?”, “What recommendations would you suggest to make these activities better?”, and “What are your favorite ways to spend time with your child?” To answer the research question, Can take-home activities encourage and stimulate parental and family involvement?, inductive open coding was used to determine reoccurring themes in the participant’s responses.

Findings

Quantitative Findings

For the quantitative findings, the following variables were examined using descriptive statistics: parent/guardian attendance at Head Start programs and parental involvement. The independent variable is how often parents attend programs at Head Start. Of the eleven responses, five parents responded often, two parents attended sometimes, three parents attended rarely, and one parent never attends. Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for this variable.

Table 1

Parent/Guardian Attendance at Head Start Programs

Note. N=11

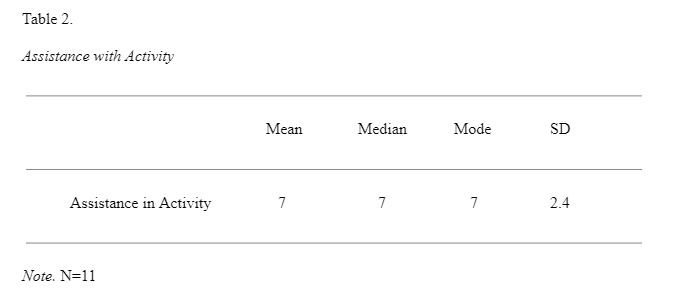

The dependent variable for this study was how much assistance was given to the child during the activities. The mean for assistance with activities was seven, the median was seven, the mode was seven, and the standard deviation was 2.4. Descriptive statistics for this variable are in table 2.

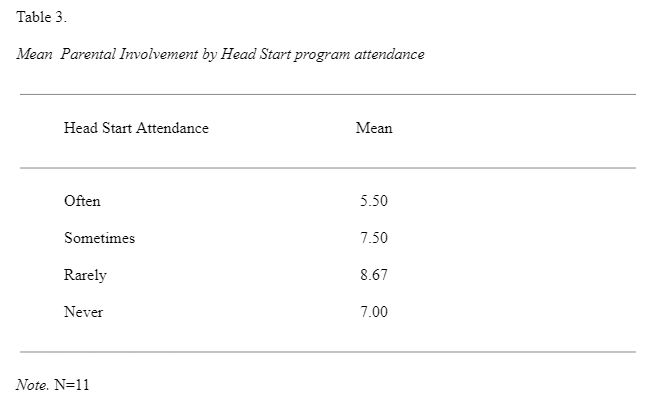

A bivariate model was run using variables v6 and v35. Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics between parent/guardian attendance at Head Start programs and parental involvement. Previous research shows that parents are most involved in their children’s lives when they are in the earlier educational stages including attending school functions, events, and programs (Hornby & Lafaele, 2011). The research the study analyzed implied that parent involvement varied greatly between parents/guardians who attended Head Start programs often (5.50) and those who rarely attended (8.67). Statistics are shown in Table 3.

Our original hypothesis was that if parents enjoyed the take-home activities there will be more parental involvement within the Head Start program. After looking at the bivariate model, it seems that the parents who rarely attend Head Start programs assisted their child more.

Qualitative Findings

11 survey responses were coded through coding analysis. Three themes that stood out were identified throughout the analysis were: spending family time together, crafts/drawing/painting, and expressing happiness or enjoyment within the activities.

The theme, “spending family time together” appeared in five out of the 11 surveys submitted. Respondent 1 stated, “These activities made it so easy and stress free to do something together.” Respondent 2 stated, “Spending time together, and learning new things” is what they enjoyed most most about these activities. Respondent 3 stated, “The family time we spent together.” Respondent 6 stated, “Being together and helping each other”. Respondent 9 stated that they enjoyed “the fact that the rest of the family was interested in participating as well”. Something that all of these had in common was that these activities gave the children and their families an opportunity to have an enjoyable and interactive experience among one another. If the activities are simple to set-up, simple to create and simple to clean up more parents and families would be more likely to participate and have more enjoyment in the activities due to them being less stressful in the end.

The theme, “crafts/drawings/paints” appeared four times out of the 11 surveys submitted. Respondent 1 listed “arts/crafts” as one of their favorite ways to spend time with their children. Respondent 5 stated, “We love arts and crafts”. Respondent 6 stated, “Reading and playing house and painting”. Respondent 8 stated, “drawing (with chalk on sidewalks)”. Respondent 11 stated, “crafts” was one of their favorite ways to spend time with their child. This theme was fairly common throughout the surveys in some type of way. This shows that parents and their children enjoy hands-on activities where the children have an opportunity to learn a new skill, while at the same time having the creative freedom to create whatever comes to their minds.

The theme, “happiness or enjoyment” was seen throughout four of the 11 surveys submitted. Respondent 2 stated that they enjoy “Doing fun activities” with their child. Respondent 3 stated, “Loved him being so happy doing the activities”. Respondent 4 stated, “It brought a lot of fun and laughter for our family”. Respondent 10 stated their family enjoyed “Having fun” after the activities and their favorite ways to spend time with their child is “doing fun activities”. The families who responded seemed to have thoroughly enjoyed these activities because it gave the children, parents, and other family members who participated a chance to see the enjoyment or happiness their child or themselves were showing around them. A big part of this I believe ties back into the theme one where spending the time together created happiness, but the activity is what brought them together.

Overall, there were five appearances of the theme spending family time together throughout the 11 surveys, four appearances of the crafts/drawings/paints theme, and four appearances of the happiness or enjoyment theme. Throughout all of the responses, the majority of them were extremely positive when it comes to the activities that the children and their families participated in. Some of the surveys had no responses while others mentioned issues with the activities such as a losing the directions paper. Since most of the surveys returned were positive when it comes to family involvement and parent-child interaction, parents can become more involved within the school setting (Ansari & Gershoff, 2015; El Nokail, Bachman, & Votruba-Drzal, 2010).

Conclusion

The goal of this study was to see how parental involvement at home compared to and effected parental involvement in the Head Start program. We had a total of 11 responses after activities were completed with surveys attached. The hypothesis created before the study was the more involved a parent or guardian is at home the more involved they will be at Head Start. The study found that the parents or guardians who rarely attend Head Start were the ones who assisted at home the most during the take-home activities.

Comparing the hypothesis to the results, it seems that no matter how much a parent is involved at home and the relation to attending Head Start programs, some parents are more involved with their child/children at home. Others may want to spend more time with their child at school. Overall, the children still get parental involvement in one way or another.

Throughout this study we had many limitations. The biggest limitation would be the response rate of the Head Start parents. We sent out 51 surveys and only received 11 in return, making it a 22% response rate. Second, Head Start was closed last year due to COVID-19 and parents may not be used to returning items back to the school as they normally would; and some Head Start programs may not be back up and running due to the pandemic. The last limitation that could have caused less surveys to be returned was the ‘reward’ for filling out the surveys. In previously years, gift cards were sent to the parents upon completion, this year books were sent in replacement.

References

Ansari, A., & Gershoff, E. (2016). Parent involvement in head start and children’s development: Indirect effects through parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 78(2), 562–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12266

Bower, H. A., & Griffin, D. (2011). Can the epstein model of parental involvement work in a high-minority, high-poverty elementary school? A case study. Professional School Counseling, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759×1101500201

El Nokali, N. E., Bachman, H. J., & Votruba-Drzal, E. (2010). Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Development, 81(3), 988–1005. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01447.x

Epstein, J. L., & Dauber, S. L. (1991). School programs and teacher practices of parent involvement in inner-city elementary and middle schools. Elementary School Journal, 91(3), 289. https://doi-org.proxy.longwood.edu/10.1086/461656

Head start programs. The Administration for Children and Families. (n.d.). Retrieved November 19, 2021, from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ohs/about/head-start.

Hornby, G., & Lafaele, R. (2011). Barriers to parental involvement in education: an explanatory model. Educational Review, 63(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2010.488049

Khajehpour, M., & Ghazvini, S. D. (2011). The role of parental involvement affect in children’s academic performance. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 1204–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.263

Smith, J., Wohlstetter, P., Kuzin, C. A., & Pedro, K. D. (2011). Parent involvement in urban charter schools: New strategies for increasing participation. The School Community Journal, 21(1)Zigler, E. F., & Muenchow, S. (1992). Head Start: The inside story of America’s most successful educational experiment. Basic Books.