The Effects of Family Fun Time Activities on Parent Involvement

Alexiss S. Brown

Department of Sociology, Longwood University

SOCL 345: Social Research and Program Evaluation

Dr. JoEllen Pederson

November 29, 2022

Abstract

Parent involvement in student education is evident of academic success. However, demographic barriers prevent parents from accommodating the academic needs of the child. Previous research has revealed that low-income families display low involvement in school activities (Alameda-Lawson & Lawson, 2018). Limited activities and programs are available for families to engage with their children and provide academic support. The purpose of the present study is to examine the effects of family fun time activities on parent involvement. Specifically, this paper will address whether race affects family involvement. A questionnaire was created by students at Longwood University to evaluate family fun time activities. A non-probability sample of 99 children were used from local Head Start programs and the Andy Taylor Center at Longwood University. Parents and/or guardians completed the questionnaire with items that addressed enjoyment of activities, completion of activities, demographic information, and family involvement. A mixed methods study was conducted using both the open-ended (i.e. qualitative) and close-ended (i.e. quantitative) items on the questionnaire. Patience, family quality time, and developing fine motor and cognitive skills are prominent themes evident in the responses from the questionnaires. The average for family involvement was 9.36. This finding suggests an increase in family involvement because of the family fun time activities. A bivariate analysis was conducted between race and family involvement with no clear pattern. This finding suggest that race may not affect family involvement. Schools across the country can implement programs or activities similar to family fun time activities to increase family involvement.

Keywords: parent involvement, race, family quality time, activities

The Effects of Family Fun Time Activities on Parent Involvement

Parent engagement contributes to the overall well-being and academic success of a child. Previous research has shown that low family involvement leads to behavioral issues and academic failure in children (Lechuga-Peña et al., 2018). In addition, research has revealed a positive correlation between low family involvement and low-income families (Alameda-Lawson & Lawson, 2018). Existing literature has examined family involvement on different variables such as household income, level of education, household type, and race (Alameda-Lawson et al., 2018; Baker et al., 2018; Gross et al., 2019; Lechuga-Peña et al., 2018; Oswald et al., 2017). Consistent findings have revealed that lower levels of education, single-parent households, low income, and minority families tend to exhibit lower parent engagement. Implications in previous studies suggested developing programs targeted at increasing family involvement. However, the creation and implementation of such programs and activities remain unaccounted for. The present study aims to examine whether or not family fun time activities increase family involvement. This study will also explore race and how it affects family involvement. Overall, the purpose of this study is to investigate the differential changes in family involvement as a result of family fun time activities.

Literature Review

Past research has emphasized the importance of family involvement on the academic success of a student. Not only does family involvement contribute to higher academic performance but it also increases children’s overall wellbeing and social competence (Oswald et al., 2017). Parental care and engagement promote a healthy and balanced lifestyle for the child. However, several factors affect family engagement and limit the scope of academic success for the child. These factors are certain demographics that potentially inhibit a family’s ability to properly engage with their children. These demographics are characterized by socioeconomic status (SES) and race. Previous studies have revealed that families representing the minority population with a low socioeconomic status exhibit lower family engagement (Lechuga-Peña et al., 2018). Furthermore, research has implicated that programs and family activities are necessary to facilitate greater family engagement and increase academic success (Alameda-Lawson & Lawson, 2018). Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the success of family fun time activities on family involvement in both Head Start programs and the Andy Taylor Center at Longwood University. We expect family involvement to increase as a result of completing family fun activities on a daily basis.

Parent Involvement

Children with parents involved in their academics tend to excel in the classroom and later in life. Parent involvement is a critical component in a child’s development. This is apparent in Epstein’s parent involvement model. Epstein (1995) proposes six elements that are necessary for both families and schools in order to improve the quality of education for the children. These six elements include parental involvement at home, effective communication between parents and schools, parent volunteering, at home learning practices, shared decision making, and community partnership (Epstein, 1995). Partnership is a central theme in Epstein’s (1995) model that combines the efforts of schools, families, and communities in creating a caring educational environment for the children. However, recent studies have concluded that not every element of this partnership is positively associated with academic achievement. Harris and Robinson (2016) proposed a new framework for parental involvement that focuses on broadening the horizons of the child rather than effecting a particular academic outcome. This new framework utilizes stage-setting to refine the elements of traditional parental involvement by emphasizing two components. The first component involves conveying the importance of education to the child and the second component highlights creating and maintaining an environment in which learning can be maximized (Harris & Robinson, 2016). Epstein’s model is not a conventional framework for families that possess certain hardships such as low socioeconomic status and racial barriers. This is evident in Gross et al. (2020) research that explored how parents, teachers, and staff members defined parent engagement. Findings revealed that only one school-based activity “volunteering in the classroom or on field trips” was seen as a relevant indicator of parent involvement. However, more home-based activities were provided by participants in their definitions and the importance of trust between families and positive relationships between parents, teachers, and schools were also relevant (Gross et al., 2020). Three parent engagement models resulted from this study. One of them is called the social capital model. This model focuses on having parents feel a part of a school community that supports all its members regardless of any differences. This model is consistent with programs like Head Start that aims to provide underprivileged families with the necessary resources and support system to benefit the children (Gross et al., 2020). Overall, several parent engagement models have been established and have evolved to incorporate the different features of parent involvement.

Socioeconomic Status

A socioeconomic status barrier can increase constraints for families to actively engage in family activities. For example, parents might work long hours to provide for their children and not have the time or energy to participate in school-based activities. These findings were revealed in Lechuga-Peña et al. (2019) research which explored the relationship between receiving a housing choice voucher and school-based parental involvement among low-income Black and Latina mothers. The results indicated that mothers who received a housing choice voucher were less likely to be involved in their children’s school-based activities. This is due to the increased work hours of mothers and their non-traditional schedules (Lechuga-Peña et al., 2019). This criticism within the research can enable theorists to reconsider their definition of parent involvement and allow schools to provide more flexible ways for low-income parents to be involved in school-based activities. Furthermore, Baker et al. (2018) demonstrated the negative association between family poverty and children’s preschool achievement. Specifically, the research revealed that fathers living below the poverty line may experience different economic stressors and as a result this decreases their capacity to engage in warm, sensitive interactions with their children (Baker et al., 2018). This article proposed for future researchers to examine links between father’s work conditions, father involvement, and children’s preschool achievement. By examining a father’s work conditions, a new definition of parental involvement could evolve to include the socioeconomic barriers encountered by certain families. Although socioeconomic status is a constant hurdle to parent involvement, children with disabilities is another challenge not mentioned in the traditional parent involvement framework. The findings from Oswald et al. (2018) revealed that unintended bias is present in existing measures used to assess parent engagement. The measure showed that current definitions of parent involvement are limited to children without special healthcare or education needs (Oswald et al., 2018). From this research, a more inclusive definition of parent involvement should be incorporated to validate the needs and actions of different families.

Racial Barriers

Another challenge to parent engagement is the racial barriers faced by the minority population. Past research found that schools tend to communicate with parents differently based on race. For example, Toldson and Lemmons (2013) revealed that parents of Black children were more likely to only receive phone calls from the school, while parents of White children were more likely to receive phone calls, newsletters, and memos. This explains why parents of White children were more likely to visit the school than both Black and Latino families due the route of correspondence and minority families feeling less supported by the school community (Toldson & Lemmons, 2013). However, these results are in direct conflict with the research of Alameda-Lawson and Lawson (2018) which demonstrated that minority families were more likely to be involved with parent engagement due to cultural background and heritage. Previous research has shown that African American, Latino, and Asian families have a more collectivistic approach and value interdependency. Whereas, White families tend to take the individualistic approach and value autonomy.

In conclusion, the existing research provides insight into the concept of parent engagement and the different barriers constraining several families from participating in certain conventional activities such as PTA meetings, volunteering, and more. However, further research is needed to provide a more inclusive definition of parental involvement that identifies the activities taken place outside of the norm. By redefining this concept, a different perspective will allow schools and communities to implement more programs geared towards low-income and minority families. The present study aims to fulfill this gap within existing literature regarding the activities initiated to increase parent involvement. Five family fun time activities were created to assess parent engagement in both the Head Start program and Andy Taylor Center at Longwood University. By evaluating the effectiveness of these activities at increasing family involvement, future programs can utilize these activities to promote family engagement in various families.

Data and Methodology

Instrument

A survey questionnaire was created by the 50 members of the Social Research and Program Evaluation team at Longwood University. The survey asked both open and close-ended questions. Items on the survey were designed to evaluate SMART objectives of five activities that were completed the previous week by Head Start and Andy Taylor Center families. Items were included that also addressed demographic information, enjoyment of the activities, family involvement, and completion of the activities. Hard copies of the questionnaire were delivered to Head Start and the Andy Taylor Center.

Sample

The non-probability sample for this study was based on 99 children (ages three to five years old). Seventy-eight children attend Head Start in three counties. Head Start is a federally subsidized preschool for families with economic need. Twenty-one children attended the Andy Taylor Center which is located on a college campus, and families apply and pay for their children to attend. Attached to the questionnaire was a children’s book to incentivize families to return the survey. Guardians of the children were asked to complete the survey and return it to the preschool the next day. Teachers sent a reminder home with children to return outstanding questionnaires. This resulted in 20 questionnaires being returned. Overall, there was a 20.2% response rate. Eighteen questionnaires were returned by Head Start families and two questionnaires were returned by families at the Andy Taylor Center.

Quantitative Analysis

Quantitative analysis of the returned surveys was based on the close-ended questions. For this study, the dependent variable is family involvement. The item from the questionnaire that was used to operationalize this was, “How involved was your family throughout this activity?” The answer choices for this item were a scale from 0 to 10 (0 being not at all to 10 being a great amount). Qualitative analysis of the returned surveys was based on the open-ended questions. For this study, the independent variable is race. The items from the questionnaire that was used to operationalize this was, “What is your child’s ethnic background?”, and “What is your ethnic background?” The answer choices for these items were, “(1) Latino/Hispanic, (2) White, (3) African American, (4) Asian, (5) Pacific Islander, (6) Native American, (7) Middle Eastern, (8) Multiracial, and (9) Other.” Descriptive statistics were used to analyze these variables.

Qualitative Analysis

Qualitative analysis of the returned surveys was based on open-ended questions. The open-ended questions on the survey were, “What did your family enjoy most about these activities? Why?”, “What did your child learn from these activities?”, and “What recommendations would you suggest to make these activities better?” To answer the research question, “Does race affect family involvement?”, inductive open coding was used to determine reoccurring themes in the respondents’ responses.

Results

Quantitative Findings

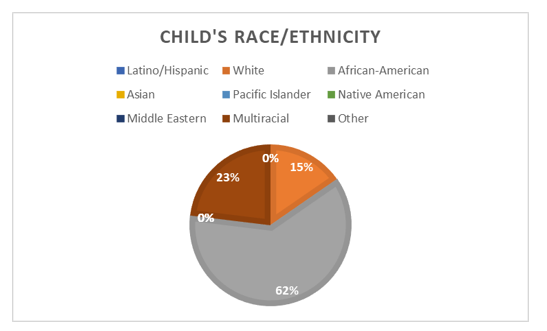

For this study, the dependent variable is family involvement. The item from the questionnaire that was used to operationalize this was, “How involved was your family throughout this activity?” The answer choices for this item were coded on a scale from 0 to 10 (0 being not at all to 10 being a great amount). The mean of the dependent variable is 9.36. The standard deviation for the dependent variable is 1.08. An average of 9.36 was reported as the family level of involvement for the activity. For this study, the independent variable is race. The items from the questionnaire that was used to operationalize this was, “What is your child’s ethnic background?”, and “What is your ethnic background?” The answer choices for these items were, “(1) Latino/Hispanic, (2) White, (3) African American, (4) Asian, (5) Pacific Islander, (6) Native American, (7) Middle Eastern, (8) Multiracial, and (9) Other.” Out of 16 surveys, 62% of children were African American, 23% were Multiracial, and 15% were White. Out of 16 surveys, 47% of respondents were African American, 40% were White, and 13% were Multiracial.

A bivariate analysis was conducted between family involvement and race. The mean involvement score for children identified as White was 9. The mean involvement score for children identified as African American was 9.63. The mean involvement score for children identified as Multiracial was 9. The mean involvement score for respondents identified as White was 9. The mean involvement score for respondents identified as African American was 9.5. The mean involvement score for respondents identified as Multiracial was 10. This analysis shows no clear pattern between family involvement and race. The mean scores for this analysis were in the high range suggesting that race may not affect family involvement. This may be due to the number of surveys received and the respondent’s ability to circle all that apply on the survey for the independent variable.

Qualitative Findings

Patience is a prominent theme evident in 5 out of 16 questionnaires. After completing the family fun activities, surveyors responded with certain virtues that their children learned from these activities. Respondent four said, “Helped with mood and to be patient.” This quote proves that by children learning patience during these activities, family involvement can increase and have a lasting impact on the child. In addition, respondent nine commented that their child learned, “Letters, numbers, and how to take turns.” This response demonstrates how the activities can influence the child’s self-restraint. In comparison, respondent ten said, “Letters, numbers, how to take turns, and also a little bit of reading.” Respondent fourteen said their child learned, “It takes time and patience to complete things but it can also be fun. This quote provides evidence of how the child understood the cycle of how patience can lead to the completion of fun activities with family. Furthermore, respondent fifteen stated, “Patience, not giving up if something doesn’t go her way or look how she expected it to.” This response demonstrates the tolerance and determination learned by a child during the completion of activities with family. Overall, these quotes prove that children learn important virtues such as patience that enable them to effectively participate in family time.

Family quality time is a recurring theme found in 6 out of 16 questionnaires. After completing the family fun activities, surveyors responded with what their families enjoyed most about the activities. Respondent two said, “So I enjoyed watching (blank) complete these activities while I assist her.” This quote provides an example of how helping behavior during the activities can result in family quality time. Furthermore, respondent eight commented, “Seeing her help me with the activities and having a good time.” This quote demonstrates a comparison with respondent two in how helping behavior can facilitate family quality time. Respondent four said their family enjoyed, “time spent together, the talks, and learning.” This response provides evidence of how family quality time can be used as a catalyst by increasing separate aspects of family involvement such as family talks and observational learning. In addition, respondent ten commented, “Doing them together. (Blank) says she loves doing things with mom and dad.” This quote demonstrates that families enjoyed completing the activities together because it builds a better family bond through family quality time. Finally, respondent fifteen stated, “Yes, we enjoyed making the finger friends the most. Spending time together and doing something educational is always fun. Family Time.” This response shows that family quality can be both fun and educational as long as the family is doing a task together. Overall, these quotes prove that completing the family fun activities improves family quality time and leads to more family involvement.

Developing fine motor and cognitive skills is a common theme that appears in 6 out of 16 questionnaires. After completing the family fun time activities, surveyors responded with skills that their children learned from these activities. Respondent one said, “Practice cutting with scissors, listening to and following instructions, and practice counting.” This comment demonstrates practical skills learned through family involvement that can apply to a range of tasks in the future. Respondent five replied that their child learned, “Colors, shapes, creativity in a fun way, and numbers.” This quote shows how family involvement in activities can facilitate a learning environment for children to thrive and learn more concepts. In addition, respondent eleven stated, “He learned shapes, colors, and some emotions.” This response suggests that by completing activities with families, children gain an understanding of cognitive and emotional skills that are essential to life and understanding the world and the people around them. Furthermore, respondent twelve said, “Shapes, finger toys, coloring, and colors.” This comment proves that the child acquired knowledge necessary for the development of fine motor and cognitive skills through completing activities with family members. Overall, these quotes suggest that completing family fun time activities with families allows the children to acquire better skills in their fine motor and cognitive abilities.

In summary, completing family fun time activities led to more family involvement and children learning important skills. As demonstrated within these analyses, completing tasks with family encourages a positive environment where children have the opportunity to grow and learn from these experiences. In the case of family fun time activities, children were active and gained an understanding of important virtues and different abilities that is consistent with existing literature. Through the use of activities, families were able to promote and facilitate an environment that supported the children.

Conclusion

Overall, this study explored the effectiveness of family fun time activities at increasing family involvement. In addition, the present study examined race and how it affects parent engagement. Findings revealed that the family fun time activities had a significant impact on family involvement. However, regardless of the family fun activity, race had no influence on family involvement. These findings shed light on future research in examining family fun time activities in other academic settings such as primary school, not just early education. Furthermore, these findings reiterate the importance of family involvement especially in academic learning. Students have an academic support system at school and at home to fulfill their greatest potential at becoming successful.

References

Alameda-Lawson, T., & Lawson, M. A. (2018). A latent class analysis of parent involvement subpopulations. Social Work Research, 42(2), 118–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svy008

Baker, C. E., Kainz, K. L., & Reynolds, E. R. (2018). Family poverty, family processes and children’s preschool achievement: Understanding the unique role of fathers. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 27(4), 1242–1251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0947-6

Epstein, J. L. (1995). School/family/community/partnerships: Caring for the children we share. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 701-712.

Gross, D., Bettencourt, A. F., Taylor, K., Francis, L., Bower, K., & Singleton, D. L. (2020). What is parent engagement in early learning? Depends who you ask. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 29(3), 747–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01680-6

Harris, A., & Robinson, K. (2016). A new framework for understanding parental involvement: Setting the stage for academic success. The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(5), 186-201. https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2016.2.5.09

Lechuga-Peña, S., Becerra, D., Mitchell, F. M., Lopez, K., & Sangalang, C. C. (2019). Subsidized housing and low-income mother’s school-based parent involvement: Findings from the fragile families and child wellbeing study wave five. Child & Youth Care Forum, 48(3), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-018-9481-y

Oswald, D. P., Zaidi, H. B., Cheatham, D. S., & Brody, K. G. D. (2018). Correlates of parent involvement in students’ learning: Examination of a national data set. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 27(1), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0876-4

Toldson, I., & Lemmons, B. (2013). Social demographics, the school environment, and parenting practices associated with parents’ participation in schools and academic success among Black, Hispanic, and White students. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 23(2), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2013.747407