Nineteen months ago, I got my dream job at Sephora. First opened in France in 1969, Sephora is a beauty retailer that has grown to about 2,300 stores in 33 countries. According to its mission statement, Sephora labels itself as being on the forefront of beauty for all, but at the time, I saw makeup as something that only girls used to make themselves more attractive if they were ugly. Because of this narrow mindset, when I first started working there, I made judgments about people. He’s a man? He probably wants our shaving stuff or cologne. A woman wearing unisex clothes with short hair? She probably wants skincare or cologne. A young girl wearing a dress? She definitely wants makeup or perfume. While checking out a client at the register, I would ask women if they were a Beauty Insider (our points program), but not men.

That behavior stopped within a few months of course, when a married man with his son behind him looked at me and said, “I’m a Beauty Insider, do you need my email or my phone number?” As I was changing my behavior and pulling my mind away from gender stereotypes, I was able to really see how society views makeup and gender. I was able to see that by me making judgments of these people, I was enforcing the gender stereotypes put forth by our society. I started to realize that I was part of the problem.

Today, nineteen months later, my heart aches at the thought of how many clients I must have treated differently due to their gender. This idea that makeup is only for femininity not only hurts men, it actually hurts women. As the beauty industry continues to explode onto our social media feeds, we are bombarded with videos of men and women with ‘perfect’ brows, eyeshadow that looks so seamless it appears (and probably is) photoshopped, and a complexion that is bronzed and blushed and highlighted to perfection.

But even though this is the expectation for women to follow along with the insane makeup trends, it is not reality for all. At work, when asking a client how I can help them, a common response from female clients is, “I don’t know what I want, but I need to start wearing makeup.” Then they go on to explain that they don’t know how to apply it ‘like those girls on Instagram’ and kick themselves. Many of them resort to saying, “I guess I’m just a tomboy.”

In our Gender & Communication class, we spent time on a piece written by Betsy Lucal called, “What It Means to Be Gendered Me.” In this reading, Lucal described what it was like to be female but not ‘perform’ her gender. She explained that ‘performing’ femininity meant following the stereotypes that came along with it, like wearing feminine clothes, jewelry, makeup, and having longer hair. ‘Performing’ masculine meant being interested in sports, wearing masculine clothes, having short hair, and being respectful of women if they are uncomfortable with her presence (since they misattribute her sex as male).

Similar to Lucal who feels that she is not ‘up to par’ when it comes to performing her gender based on her sex, these female clients who do not know how to apply makeup feel down about themselves and question their femininity. I think if society is able to expand their preconceived notions about makeup or other gender stereotypes, our children will be able to grow up in a world where they can choose to do what makes them happy, not what society expects them to do. Basically, we are able to make a change.

So where do these gender expectations start? Humans are not born with gender stereotypes in their DNA like they are born with the natural ability to eat, sleep, and reproduce.. Our definitions of gender are learned. This is at the heart of social learning theory. Developed in 1996 by Walter Mischel, social learning theory explains that humans learn how to perform a certain gender based on ‘imitating others and getting responses from others to their behaviors.’ These outside influences include their family and peers, television, the internet, and even strangers they see. This theory explains that although children imitate anything they see at first, they start to only perform interactions that will give them positive feedback.

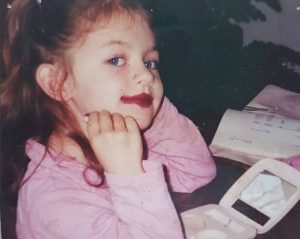

I have one example of social learning theory from my childhood. My mother has a photo of me as a young girl with her makeup compacts spread out over the table, lipstick smeared around my lips, and a proud smile on my face. I didn’t get in trouble for making a mess, I actually earned the name “makeup queen” by my family and they praised me for how “girly” I was. In contrast, my brother tried to play with her makeup and was scolded for making a mess. He was given dirtbikes and Batman toys and praised when he learned how to ride a bike at the age of 4.

As we got older, I continued my love of makeup and wore it proudly in high school to cover up my blemishes and make my eyes ‘pop’. However, when my brother had a blemish in high school, he would ask me to apply my concealer on it so he could feel more confident during the day. “Don’t you dare tell anyone at school about this,” he threatened me, embarrassed. His desire to use concealer to cover a blemish was the same as my desire to cover a blemish, yet he couldn’t openly talk about it for fear of being mocked by his peers or scolded by my parents (mostly my mom). This shows that as children, we payed attention to which behaviors were ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for our gender and we acted accordingly.

Even makeup brands who say they are accepting can help contribute to our children learning gender stereotypes. According to a study done at the GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies, brands with female representation in their advertisements have products labeled with stereotypical female labels, like “China Doll”, “Feminine Dangerous”, “Striptease”, and “Orgasm” (a pink blush with micro glitter). This can cause children to grow up seeing famous females representing these brands, associating them with these stereotypical names.

A continued negative side effect of this theory comes into play when a person feels they are unable to perform their gender although they are aware of the expectations, just like the female clients who are disappointed in themselves because they struggle to makeup. This also comes into play when men would come into Sephora and, because of how I learned gender growing up, I would expect them to act a certain way and react to them if they did not fit my idea of what masculine was. My reactions were usually surprised rather than supportive and helpful.

But fortunately, I overcame this way of thinking, and I found that it made a difference at Sephora. I try to treat everyone the same, regardless of gender, and I have found that clients trust me more now that I am open and accepting to their needs. I have also found that by communicating the importance of self confidence and not striving to be what someone else expects you to be based on your sex helps them feel empowered. I think if other people do this too, with their peers and children, our society and children will be able to themselves in any way they choose; not just limited to their gender stereotypes.