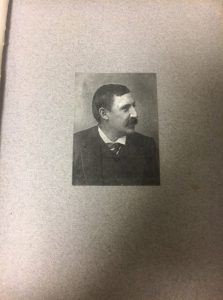

John A. Cunningham (1909 Virginian)

Pg. 38-42 of the 1909 Virginian (State Female Normal School Yearbook)

“John Atkinson Cunningham, L.L. D.

John Atkinson Cunningham was born on June 24, 1846, in Richmond, VA. His paternal grandfather, Edward Cunningham, came from County Down, Ireland, to Virginia, about 1770, and made a large fortune by iron works near the present site of the Tredegar mills and by a line of county stores which extended from Virginia nearly to Ohio. His children received a most liberal education and his son, John A. Cunningham, Sr., the father of the subject of this sketch, received his academic training at William and Mary, and Harvard, and graduated in medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in 1825. He afterwards studied in London and Paris and was entered at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, under Sir William Lawrence. He married Miss Mary Johnston, a granddaughter of Peter Johnston of Longwood near Farmville, VA., and a cousin of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston.

Of this marriage John A. Cunningham, Jr., was the only child. He was a very delicate child and received most of his early education from a French governess at home, gaining in that way a rare familiarity with the French language. Afterwards he attended private schools, in the home of his uncle in Powhatan County, and in Fauquier, under Mr. Jacquelin Amber. Immediately before the breaking out of the Civil War he was a pupil at New London Academy, Bedford County. At the age of seventeen he entered the Confederate Army and served as private until the end. After the war he pursued his studies at the University of Virginia, where he graduated in Chemistry, Latin, Moral Philosophy, Natural Philosophy, Pure Mathematics, French (Language and Literature). He afterwards received the Master’s degree from the University of Nashville. In 1896 Hampden-Sidney College gave him the honorary degree L.L. D.

After leaving the University of Virginia Mr. Cunningham was made professor of Latin and Greek in Western Military Academy at New Castle, Kentucky, under Gen. Kirby Smith, and when General Smith was made Chancellor of the University of Nashville Mr. Cunningham was elected to the chair of Latin, where he remained until the University of Nashville was bought out by the trustees of the Peabody Fund and changed into a training school for teachers.

In 1874 Mr. Cunningham married Miss Florence Boyd, of Nashville, who lived out more than a year. In 1887 he was again united in marriage to Miss Martha Eggleston, daughter of Mr. Stephen Eggleston, of Cumberland County, Virginia. For a short time after leaving Nashville Mr. Cunningham was in business in Richmond, as a druggist. In 1877 he was made principal of Madison School, Richmond, where he taught with great success until he came to Farmville.

The ten years of Dr. Cunningham’s connection with the Normal School were the most important, the most fruitful and successful of his life. During his administration the school grew steadily, though not rapidly. The first year there were ninety-three enrolled in the Normal School Department; the last, there were two hundred and fifty. His great ambition was to make character and develop the mind. In order to accomplish the first he felt it to be necessary to put each individual, to the farthest extent possible, upon her own resources; to have few rules and as little surveillance as could be, consistently, with his duty to parents and children; to teach truth and honor by trust, and to punish severely when this trust was betrayed. To develop the mind, “his method, “writes one of his teachers, “was Socratic, with additions of his own. Students that were pretty well up on a subject he forced to go deeper into it by showing them they had not grasped it thoroughly; the timid, undeveloped minds he encouraged, and when they realized they could answer some of his questions he led them on till they were induced to do real work. As he expressed it, he ‘made them mad with themselves.'” The same teacher says, “I have never known more than two, or at the most three, teachers who made the subject they were teaching so clear and at the same time made the students do his own thinking.” And again, the same teacher, “I realize that any efficiency I have as a teacher is in large measure due to him, yet when I think of summarizing my experience, it all resolves itself into, ‘he had life and it flowed into those he touched.'”

Perhaps natural science and mathematics were his favorite studies, though he seemed equally at home with all. “In teaching science, “one who was both a pupil and a teacher under him, writes, “his method was humanistic; that is, that the science teacher should make the great scientists live before his pupils—their lives, the manner in which they made their great discoveries, the steps leading up to them emphasized. Especially did he advise this method with girls like ours who have so short a time.”

He was constantly reading and thinking, trying to put the school upon broader lines, but it was always the personal contact he insisted upon. There was no department of the school the details of which he was not familiar with, and no girl or teacher he did not know well. Dr. A. D. Mayo, who visited a great many schools in the interest of the Peabody Fund, said this was the best Normal School in the South, though at that time several far outstripped it in numbers and material equipment.

The qualities which most distinguished Dr. Cunningham were originality of thought, strength of purpose, sympathy, and a sense of humor. Of these, perhaps, his sense of humor was the most valuable in the management of the school, in steering him through the difficulties and opposition with which his ideas and methods were frequently met. Many a strained situation has been instantly adjusted by a laugh, a timely anecdote; many a girl has been turned aside from a course of action which, if followed, would certainly have brought her trouble, by a twinkle in the eye, a whispered word, a shrug of the shoulder which, as by a flashlight, showed her the ludicrous side of her conduct.

His sympathy was broad and deep, especially for those who were struggling for an education. While he was president the King’s Daughters Society was organized, the object of which was to raise money as a loan fund for those who would be forced to leave school without such help. There was never anything in the school in which Dr. Cunningham took a more lively interest. It is for that reason his friends have worked so hard to establish a fund as a memorial to him, bearing his name, which will go on doing that work.

As to his religious life no better words can be used than those in a recent magazine article on Mr. Cleveland: “He pondered much, though he said very little regarding his religious belief. Yet it was always there, deep within him, as they know best who knew him well.”

Many can testify that when tempted to do an ignoble or unjust deed, when filled with bitterness and wounded pride, thinking only of self, a talk with Dr. Cunningham has soothed and calmed them, because he had gently shown, by a half-spoken word, a reference to the teachings of childhood, how far were such thoughts from the precepts and example of our great and lowly Master. Nothing that pertained to the general uplift of the school, its real religious interests, was viewed by him with indifference, and in the spring of 1896 the Young Women’s Christian Association was organized. We all know what a power for good that has become.

Eleven years have passed since this active brain and sympathetic hear were stilled forever in this life. The school has gone on in an ever-increasing prosperity. All honor to those who by work and tact have brought it to its present position. But, while walking through its beautiful halls, and enjoying and admiring its present conspicuous success, it is well sometimes to take a backward glance, lest we forget the man who established it and saw it in its small beginnings, and him who bore the burdens and heat of the day, who toiled for it and died in its service—John A. Cunningham!”