Mi corazón se queda en Chile

See corresponding photos here!

Santiago felt like home to me the minute we touched down- the warmth of the sun, the maze of streets lined with cafes, panaderias, bars, and bookstores; the apartment buildings studded with balconies like eyes, each overflowing with houseplants and fresh laundry; the people so openly in love; the music.

I write this to you from the floor of my living room, back at home in Richmond, Virginia. My heart aches for all that I left behind in Chile- from the mountains to the sea. Not a day went by when my cohort and I weren’t connecting with inspiring people, visiting profound sites of memory, resistance, violence, innovation, tragedy, and triumph, and/or having conversations about how important it is to actively and critically seek out the truth in a deeply politicized world that buries the ugly (especially under the gaze of foreign students and tourists), and about how beautiful it was for us to be able to experience life in yet another brand new place. Each time my peers and I hopped continents and country lines in the past three months, it was as if we were reborn a little- with fresh eyes and a growing repertoire of knowledge about the international and local contexts that surrounded us- each time, we arrived ready to investigate and appreciate and consider.

Now that I’m home, I can already tell that it will be tricky to cultivate that same sense of awe, of newness and radical intellectual expansion in an environment that is familiar and comfortable. But I hope that this blog, alongside the photographs, my friendships with peers and connections with professors, and the memories of all that I saw and learned- and how it felt to be so inspired- will help me to stay energized and alert, especially as I begin to look for ways to incorporate what I’ve taken away from this experience into struggles for justice in my own community. But enough reflection! I have a whole different essay to write about that for Longwood. Lemme tell you about two of the most profound memories I have from communities and organizations we visited in Chile- spending time in Curarrehue with the women of Feria Walüng, and our site visit with Mujeres de Zona de Sacrificio Quintero – Puchuncaví en Resistencia.

A Week in Curarrehue

The rain began to fall just as Sarah and I settled into the rhythm of our task- I heaved the hoe over my shoulders again and again, yanking it up and back towards my body after it bit into the dirt, relishing the sound of roots being loosened by its metal jaw. Sarah was crouched alongside the bed of mint, carefully and determinedly pulling the weeds and grasses that had grown too close to the mint to safely remove with the hoe. When my arms got tired, Sarah and I switched jobs. And then we switched again, and again, as the misty rain swirled around us and mixed with the sweat on our brows.

It was cold, and the breeze made the rain blow into our faces- but Sarah and I were in silent agreement that we would continue to work until we were fully satisfied with the labor we’d contributed. Raquel, the beautiful, kind-hearted Mapuche woman who had opened her home to Sarah and I for the week, had done everything in her power to ensure that we were comfortable, well-fed, and happy. And although Sarah and I always made sure to do our dishes and we often helped cook dinner (I’ve never made or eaten so much delicious, fresh bread in my life…) we were eager to convey our gratitude with some manual labor on her farm.

Raquel has lived in Curarrehue for most of her life. She is a farmer, an excellent cook, an artisan, a feminist, and a community organizer. She is deeply involved with Feria Walüng- a community organization founded in 2005 by an inspiring group of Mapuche women who recognized 1) a need for economic opportunity in their rural, indigenous community, 2) a need to preserve their cultural traditions in an ever-modernizing world and in a country that does not recognize indigeneity as an identity worthy of distinction or protection, and 3) that their social positions as community caregivers had already given them the community organizing skills they needed to create some radical change. Throughout the week that we spent in Curarrehue, I saw Raquel’s story reflected in the lives of many other inspiring Mapuche women. Raquel had to fight hard for Feria Walüng to become a reality and for her right to engage in social and economic activities outside the home, as did all of the organization’s founders. Now, like many of them, she is highly respected in and around her community as a leader, an activist, and an entrepreneur.

Feria Walüng, which means “Fair of Abundance” in Mapuzungun (the indigenous Mapuche language), hosts an annual cultural fair and seasonal workshops that educate visitors about Mapuche traditions and culture while also helping to keep these traditions alive within the local community. The fair and workshops give foreigners and locals alike the chance to take a deep look into the community’s way of production and to engage with material and spiritual aspects of Mapuche culture, such as weaving, enjoying traditional Mapuche dishes, casting pottery, listening to and making music, and learning about the ongoing struggles/supporting the ongoing resistance of the Mapuche people. The fair is all about promoting autonomy, envrionmental responsibility, food sovereignty, speaking and writing in Mapuzungun (which the Chilean state treated as an act of terror during Pinochet’s dictatorship, and continues to discriminate against today), and recovering ancestral knowledge.

The triumphs and challenges faced by the Mapuche community in Curerrehue were brought into even clearer perspective as we learned more about the history of intense systemic oppression of, and state violence against, the Mapuche people. We learned that although the Mapuche were able to resist the occupation of their ancestral homelands for three centuries after the Spanish began colonizing Chile, the founding of the Chilean State in 1810 and the creation of the Chilean army eventually led to the military occupation of Mapuche territory in 1881. This was part of a violent campaign by the Chilean government to remove the Mapuche people from their ancestral homelands and forcibly relocate them to government allotments called “reducciones”. The total land area of these allotments comprised only 6.3% of the Mapuche’s original territory, drastically reducing their ability to survive culturally and materially, and to participate in critical nation-building processes.

These historical events set a precedent of exclusion that has been difficult to dismantle. While the state of Chile has had seven Constitutions, the first enacted in 1818 and the last during the reign of Pinochet in 1980, not a single one has recognized indigenous people. However, resistance has also always been a part of life for the Mapuche community- throughout Pinochet’s dictatorship, indigenous Chileans demonstrated massive organized resistance to the violent, authoritarian regime, including negotiations with major political parties for Constitutional recognition and the protection of their rights to land, natural resources, and political participation. Although many of these rights have yet to be formally approved by Congress, significant progress was made in terms of indigenous people’s legal recognition as ethnic communities, the official acknowledgement of indigenous language and culture, the protection of the lands (and the natural resources on said lands) where indigenous people were forcibly relocated, and the establishment of CONADI, the National Corporation for Indigenous Development. Unfortunately, the state’s appropriation of indigenous lands and natural resources has continued, often without any consultation of the indigenous communities themselves. The struggle for Constitutional recognition and the right to self-govern persists, without which indigenous people will never be able to fully, equally, or equitably participate in the “democratic” process of Chile’s development as a nation.

Learning about the socio-historical context that has set the stage for the current situation of the Mapuche community, and then having the opportunity to witness the strength, devotion, creativity, generosity, and kindness of the families we stayed with and of the women of Feria Walüng, was deeply inspiring. It all goes to show that self-sufficiency is resistance. Knowing your roots and practicing your culture is resistance. Recognition as a person under the law is a human right enshrined in the Universal Declaration, and until the full human rights of Mapuche people are recognizes and protected by the Chilean State, I know that Raquel and her compañeras will not rest- they will garden, they will speak in schools, they will keep their traditions alive and welcome strangers into their homes. I aspire to be as hard-working, as devoted and open-hearted. It’s a rare and wonderful blessing to hold such powerful memories of time spent with, and lessons learned from, Raquel and her community in my heart and mind.

Quintero-Puchuncaví & the Mujeres de Zonas Sacrificio en Resistencia – Valparaiso

Rust-colored tendrils of seaweed and the dilapidated body parts of hundreds of crabs crunched underfoot, all baking in the sun where the tide had left them. A seagull lay in a fetid, fly-covered, feathered heap in the sand. The silver head of a fish with blank, milky eyes stared unblinkingly into the sky. These were just a few of the indicators of deep ecological sickness on the beach where we stood–pipes jutted from the sand, extending their knuckled fingers far out into the dark, salty water. Smokestacks stood watch over the waves, protruding from a mess of barbed wire and blank industrial warehouses from the coal-powered energy plant just across the street from the shore.

Over the course of the day, my cohort and I visited three sites of ecological and environmental damage in the Quintero-Puchuncaví area, which was established as a “sacrifice zone” (an area “sacrificed” for population by dangerous, dirty, highly profitable extractive industries) by the Chilean government in the 1950’s, and was then declared a “saturated zone” for particulate matter and sulfur dioxide in 1993. The first site was the beach in front of the AES thermoelectric plant, the second was the parking lot of the Codelco copper refinery that has been poisoning a nearby wetland with toxic byproducts from the refining process for nearly a century, and the last was a beach that had been leveled due to the recent expansion of one of Quintero Bay’s 14 remaining coal-powered energy plants (down from 28 in 2019).

Katta Alonso (a lifetime environmental activist and resident of Quintero) and a few other representatives from the Mujeres de Zonas de Sacrificio en Resistencia Quintero y Puchuncaví (a women-led conservation NGO) traveled with us to each location and offered insights and explanations as to how these industries arrived in Quintero-Puchuncaví and how their operation harms surrounding ecosystems and communities. Since the organization’s founding in 2015, the Resistencia has engaged in political, legal, and research-based advocacy to bring light to the environmental injustice and human rights violations suffered by their community at the hands of extractive industries and the Chilean government.

In 2019, Katta joined forces with Senator Juan Lattore, the S24 Quintero Artisanal Fisherman’s Union, and organizations from the Quintero Hospital (which constantly receives patients ailing from conditions that result from exposure to carcinogens and heavy metals, such as cancer and neurological or reproductive disorders) to write and deliver a petition to then-President Pinera, urging him to comply with the 2019 Supreme Court ruling that mandates the implementation of 15 measures to identify the sources of contamination and repair the environmental situation in Quintero Bay. Although this ruling has not been properly upheld by extractive corporations in Quintero Bay, the attention that NGOs like Mujeres de Zonas de Sacrificio en Resistencia brought to the plight of their community led to the closure of the furnaces and boiler of the Ventanas copper smelter (one of the leading mechanisms causing pollution in Quintero), two coal-powered thermoelectric plants, and the subsequent passage of three more Supreme Court rulings that provide community organizers and local politicians with tools to enforce compliance with the 2019 ruling.

These women saw what their community needed, recognized their capabilities to organize and make a difference, and have been fighting for justice ever since. I realized, by the end of that day, that what happens in Quintero-Puchuncaví impacts all of us, no matter where we live or work, as human beings with a responsibility to each other and as organisms who depend on the resources this planet has provided us. And the power of international solidarity is immense- but it requires awareness, empathy, and action, which is not easy to generate across continents and with so many other causes in desperate need of support. But I feel like this is a good start, for me, at least- to hold Katta’s story, along with the stories of all of those who I had the honor to meet in Nepal, Jordan, and Chile- close to my heart and to continue to share my memories of their strength, determination, resilience, joy, and compassion as far and wide as I can.

December 16, 2024 Comments Off on Mi corazón se queda en Chile

Shukran, Jordan – 3 Weeks of Learning

Here is the link to photos for this post!

I threw my head back into the crisp water pouring down on me, relishing the instant sense of refreshment and relief and the delicious coolness on my scalp. The sensation was so soothing it made me want to sing- and so I did. There in the hostel bathroom in Santiago, my lungs filled with air and new life- I’ve made it to the last country of this trip. I can finally feel how close I am to the finish line, to returning home. And on the nearly 16-hour flight that we took from Amman, Jordan to get here, I had plenty of time to reflect on the past three weeks and what I learned from my time in the Hashemite Kingdom.

There are two parts of our Jordan visit that will stick with me the longest, I think. The first was our excursion to the Southern Badia region of the country, during which we walked the Sikh and wandered around Petra, we rode camels in Wadi Rum, we met, spoke, drank tea with, and learned from members of the native Bedouin tribe, and we basked in the beauty and geographical significance of Aqaba- Jordan’s only coastal town. I will never forget standing on the rocky beach on the edge of the Red Sea, looking out into the dusky evening sky and being able to see a sliver of Sinai Peninsula of Egypt and a fragment of Palestine off in the distance. It was profound to stand there and to realize how deeply interconnected the Middle East has been since the dawn of time, and to be there as a student experiencing such extreme luxury (our amazing country coordinator, Dr. Majd, put us up in a five-star hotel during our stay in Aqaba) whilst existing in close proximity to such extreme suffering, just across the water. The sky weighed heavy on the sea in-between, and it was hard not to feel guilty that we had ended up as tourists on one shore simply by virtue of where we were born and who we were born to- we did not earn our privilege, just as nobody in Palestine (or anywhere, for that matter) deserves the violence that has come upon them.

I will also never forget our site visits during our excursion to the South. We made multiple visits to women-led and women-run community-based organizations that seek to help Bedouin women generate income- this is important work, because Bedouin women face serious social, economic, and geographic barriers to financial autonomy (which often acts as the catalyst for other forms of female empowerment in the home and community). The Disi Women’s Cooperative was my favorite of such organizations- it was founded by a Bedouin woman who recognized a need for income-generating activities and female social empowerment in her community. Like many rural areas around the world, Jordan’s Southern Badia is less developed, more politically and socially conservative, and more geographically isolated than Jordan’s urban centers (Potter, 2023). As such, women who reside in this region tend to face even stricter regulations pertaining to their mobility, their right to assembly, their freedom of speech, and their right to decent work than do urban women in Amman. In response to these issues, the Disi Women’s Cooperative helps teach rural women how to create and run successful in-home businesses where they sell products they learn to create at the Cooperative, such as hand-woven rugs and tote bags, dishware and sculptures made of pottery, and Bedouin medicinal remedies made from native herbs that the women grow and harvest themselves. Women also have the opportunity to advance their English skills at the center by taking language classes, and they are able to form friendships and networking connections with other women who participate in Cooperative programming (2023). It was amazing to see what these women were capable of withstanding and overcoming simply by having a space to call their own- a space to organize, plan, exchange ideas, sympathize, heal, and create together.

The second part of our time in Jordan that meant the most to me took place on our excursion to the North- to Jarash, Ajloun, and the small village of Najdeh. While in Najdeh, my peers and I were given an unprecedented opportunity. For roughly two hours, we were able to meet and speak to four Palestinians who are survivors of persecution and displacement as a result of conflict and genocide by Israeli forces in Palestine. Two of our speakers live in Gaza camp and two in Souf camp, two of Jordan’s largest refugee camps. There was one man- Majed, a slender man in his mid-50s who is a schoolteacher in one of Gaza camp’s UNRWA-funded, 2-shift schools- and three women- Betool, a photographer and writer who teaches youth photography in Gaza camp, Hanaan, a CBO organizer and the director of the Women’s Committee in Souf camp, and Lubna, who recently earned a masters in Nursing after also completing a PhD in environmental engineering.

The speakers took turns answering our questions and sharing bits and pieces about themselves- Majed was born in Gaza camp and has never even seen Palestine, but he has spent his entire life fighting for a future there and strengthening the minds of younger generations so that they might have a better chance at freedom. Betool captures the lifeblood of community, hardship, joy, and resistance in Gaza camp with her moving photographs, which she posts online and spreads around the world. Hanaan works with women in Souf camp to help them raise their voices and find comfort in the support of other women. Lubna continues to volunteer in her community to “make herself useful” while she applies for jobs- having 2 PhD’s has thus far failed to shelter her from Jordan’s unemployment crisis. Majed said something that struck me as very surprising towards the end of our conversation- after being asked, “What message about Palestine do you think it’s most important for us to take back to the U.S, as students and as ambassadors for your nation’s cause?” he said, “Remember that Palestine will never forget what the American students have done for us. There is no bad blood between Palestine and the American people- We are grateful for the awareness you have brought to our struggles.” While Majed was speaking on the behalf of many people in that moment, the others nodded along with him. A sense of awe came over me. I could not believe the emotional capacity of this man- to have seen and felt so much death and destruction at the hands of U.S tax dollars sent in twisted military care-packages to Israel and to re-iterate to us that he has love for the American people?! The strength, the kindness, the perseverance, the resilience of his spirit swallowed me whole.

The rest of our time we spent back in Amman, visiting other CBOs and CSOs and attending lectures on topics that included Islamic Feminism, the history of British occupation in Jordan, and the 1993 Israel/Palestine peace treaty in the context of all that has happened since. It was after one of our Israel/Palestine lectures that Dr. Khan stepped up and gave us a timeline of U.S involvement in the Middle-East from the Cold War onwards. Listening to him speak about this was the very first time I had ever heard about the Soviet Union and the United States’ tug-of-war in Afghanistan, the U.S’s state sponsorship of the Mujahedeen through provision of weapons, the establishing of schools that taught extremist Islamic ideals and created child armies… I fought tears of frustration as I listened to Dr. Khan speak. I felt so ashamed to have lived 20 years without knowing or understanding the depth of the violence that my country has created, funded, and inflicted on this region of the world. Later that day I wrote a poem about it, which I’ll include here.

Another American Evil I Didn’t Know About Until Last Week

It reeks of U.S…

forced entry at a vulnerable hour,

proudly cloaked in moneypower,

that we sucked out of Black others,

and then we taught you to be extreme.

In this warped institution, under the US constitution,

AKs should shoot semicolons at the ends of holy passages and holy people.

Put down the pen and gather reams of information.

Gun-metal gleaming In the hands of angry children,

looking for anyone to blame but God.

And when we did not love your angry

children,

and they used the weapons given by U.S.

to try to burn U.S. down,

we trained terrier meatheads to track

the scent of a terror that’s traced to our teachings.

Unearthed were the strings,

sewed into the soft backs of angry child puppets,

as we pulled them by their wrapped heads to the altar of US national security.

Executed for executive protection.

We know that the hearts of our men hurt

as they kill ancient brothers in the name of what we call justice,

but justice has its fingers broken from clawing at the choppers when they leave it behind, crying

on the tarmac, knowing it will die.

And everyone knows that freedom matters

more than human life,

when the human in question does not

flatter U.S.

Nothing more than a poor, angry child with the gun that we hired as it’s babysitter;

It grew up to be a killer and

decided where revenge was best sought.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

I left Jordan a different person than when I arrived. I feel as though I have a significantly broader and deeper understanding of the yawning gap between what it means to be a woman in America versus a woman in Jordan versus a woman in Afghanistan, etc; What it means to be an American passport holder versus what it means not to be one, I recognize now that even with all that I have learned, there is so much I will never know. There is so much I will never understand about the suffering of others. But I must keep making efforts, each and every day for as long as I am alive, to learn more and to empathize and sympathize with more and more people from as many different contexts as possible.

I think that as Americans, we all have a duty to become global citizens- a duty necessitated by the insanely disproportionate amount of global influence our nation possesses, often at the expense of families we will never know the names of. I am extremely grateful for the freedoms that my country has provided me- I am hyper-aware of how insanely mobile and autonomous my life has been thus far, even just after 20 years of life- and at the same time, I recognize the unfairness of my nation’s historic and current actions and of my unearned advantages within and because of it all. I want to do everything I can to make room in local and global circles (to the tune of Bernice Johnson Reagon) and to continue to learn from the voices and stories of women like the members of the Disi Cooperative and Betool. I can’t wait to see what opportunities and knowledge Chile brings. Until next time.

November 8, 2024 Comments Off on Shukran, Jordan – 3 Weeks of Learning

Week 1 in Jordan – Learning the Ropes of an Ancient City

- I am including all the photos for this post on this Google folder because this site doesn’t have the bandwidth to accommodate both my yapping and lots of pictures! Click the link for Jordan flicks!

As I bit into the flaky, crisp layers of golden phyllo punctuated with bright green pistachios, I was immediately soothed by the sensation of a sweet, nutty, buttery flavor melting in my mouth. My friends and I had sat down in the corner of a small, crowded bakery in downtown Amman, but in that moment we could have been anywhere in the world… all that mattered was the decadent pastry that clung to my fingertips and lips–I was SO. HUNGRY. As my peers and I discovered, the meal-time schedule is a little different in Jordan compared to what we had grown used to in the States and Nepal. On the Friday evening that closed out the first full day my peers and I spent with our homestays, our student group-chat was filled with messages debriefing about who had eaten when–the breakfast range fell anywhere between 9 am and 12:45 pm, and the lunch range, similarly, fell anywhere between 1:00 and 5:30 pm. Alas, my lack of a noon-sharp lunch absolutely necessitated that Emily, Peace, and I made the bakery pit-stop. It was partly in the name of quelling my dizziness, and partly for the public safety of anyone in a close proximity–my hanger is REAL.

Earlier that afternoon, the three of us ordered a Careem (Jordanian Uber) and headed out on a mission to see the ruins of the ancient Roman citadel that stands proudly in the heart of Amman. The heat was intense–the sun blazed down upon us as we toed the dusty path up to the ruins, trying to get a sense of the history of the place from whatever snippets of English we could find posted on the signs around us. Almost immediately, Peace made friends with a young family who asked her for a picture, and before we knew it, Peace had negotiated her own photoshoot overlooking the city. Emily and I looked at each other and shook our heads, laughing. In that moment, the world belonged to Peace, and we were happy just to be living in it!

After roaming around the ruins and taking some more funny pictures, Emily, Peace and I stepped inside the Citadel Archeological Museum to try to gather some more history about where our feet stood. We were able to gather that the site has a fascinatingly layered history–We had just walked among the ruins of a Roman temple, a Byzantine church, and an Umayyad palace. Walking through the museum, the waves of Roman, Greek, Ottoman, Egyptian, and indigenous tribal influence made themselves known to us through the materials, subjects, and art-styles of the sculptures, tools, cookware, and jewelry that gazed up at us placidly from behind the museum glass. I found myself thinking about how strikingly connected the world has always been, consciously and subconsciously for all of those who inhabit it. None of us lives in isolation–many hundred years ago, the artwork of an ancient Egyptian sculptor inspired another artisan who then carried the first sculptor’s influence across a huge body of water and set it in stone in the walls of a Roman temple. Walking through the museum made me think about how my actions and thoughts impact the world in ways I may never even realize.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Over the past week, my peers and I have also had the incredible privilege of learning from and listening to a diverse group of individuals involved with the administration and dissemination of human rights principles within and alongside the pluralistic Jordanian legal system, as well as from the front-liners of many Civil Society and Community-Based organizations that target issues such as women’s rights, children’s rights, LGBTQIA+ rights, worker’s rights, free speech and assembly, and refugee rights in Jordan.

Throughout our group’s inquiry during each site visit and lecture so far in Jordan, a persisting challenge has emerged for our cohort in trying to navigate 1) the universal right and obligation of all people to identify and interrogate human rights violations around the world, and 2) the cruciality that we, as Western students and guests in a foreign cultural context, remain sensitive to cultural relativity and do not assume that we have a greater knowledge of what constitutes human rights than non-Westerners. This issue has led to some high-tension, high-emotion conversations within our group cohort, and as difficult as some of these conversations have been, I’m grateful that I am being exposed to this tricky issue as an undergrad student rather than as a grad student or as a working professional. As a result of our group conversations, I have been made aware that learning to balance the push and pull of the universality of justice/injustice and relativity of each cultural context is a skill that will serve me well for as long as I continue to engage with social justice issues, professionally and personally.

I don’t have any concrete answers, but I think my two biggest takeaways from these conversations to date are 1) Tone and delivery are everything when questioning and making statements about real or perceived human rights issues and solutions, especially in knowledge-seeking contexts such as site visits, and 2) Everyone is entitled to their own opinion about what constitutes a violation of human rights, and while nobody’s opinion can ever be totally objective, they are all based in different life experiences that are real for the individual and valid to their respective positionality.

Having said all of that, the site visits that have stood out the most to me were our trips to the National Centre for Human Rights and to the Justice Center for Legal Aid in Amman. The order in which we visited these places was also important, because I think that our site visit to the National Centre–a “legal personality” that monitors Jordan’s compliance with international human rights law and receives support and funding from the Jordanian government–informed the context in which we arrived at the Justice Center–a fully independent CSO that aims to serve citizens and non-citizens who would otherwise be excluded from the judicial process in Jordan. In my opinion, our visit to the National Centre for Human Rights felt strange and stilted in a way that I was not expecting. One of our speakers was the General Commissioner of Human Rights, who opened his presentation with a warning to us all that the media can be misleading and that it “won’t always give you the right principles to achieve the truth.” He then gave us a speech about the general importance of human rights and about our duty to resist against governments who violate them. He gave the example of totalitarian governments and explained how totalitarian governments oppress their citizens and how freedom of expression and peaceful assembly are cornerstones of true democracy (I thought this was a particularly interesting thing for him to bring up, given that Jordan is a monarchy where freedom of speech is not granted in full). He also repeatedly emphasized the importance of comparison–he stated that “comparison is crucial for reaching the depth of any discipline,” and he mentioned that compared to its immediate neighbors, Jordan upholds human rights to a high degree and prioritizes doing so.

The General Commissioner was a sweet, older man with crow’s feet at the corners of his eyes and a kind gaze, and I appreciated his words of affirmation about the importance of human rights and his perspective on how Jordan set itself apart from the socio-political contexts of its neighbors. At the same time, I was struck by how much his opening message conveyed his immediate concern that the room full of American students sitting in front of him might’ve thought that his country was “backwards” or violent and extremist, as the American media so often portrays the Middle-East to be. As he went on and on about the virtues of human rights (at least 30 minutes of the presentation was devoted to this), I found his assertions subconsciously having the opposite effect on me–we came here to discuss the condition of human rights in Jordan, not to re-hash the same frequently broadcasted slogans about why these rights matter… so what was he not telling us?

Eventually, one of his colleagues entered the room and introduced herself to us. She was also an older woman, and she explained that she was a professor of law at one of Jordan’s graduate universities and a member of the Board of Trustees for the Centre. She and the General Commissioner engaged in a back-and-forth banter that involved showering each other with accolades for a few minutes, and then the professor began to give us more detailed information about the history and purpose of the Centre. The Centre runs some very valuable programs focused on spreading awareness about, and conducting government trainings based on international human rights legislation, as well as conducting myriad inspections into how human rights are being protected by various Jordanian institutions.

As the session went on, though, the professor said some things that were very unsettling to me. At one point, she told our student group that female survivors of sexual abuse commonly face shame and pushback from their family and immediate communities when they come forward. She explained that in conservative Muslim communities, a woman’s “honor” is based on her virginity/abstinence, and each woman’s duty to uphold that honor is extremely important for the social reputation of her family. Thus, being raped is seen as a detriment to her family’s “honor”.

In light of this, I asked her about how the Centre is working to protect female rape victims in Jordan, and in response to my query, she said that “rape isn’t really an issue here” thanks to the conservative Muslim culture that prevails in Jordan. What’s more, she claimed that based on her legal experience, 95% of rape cases in Jordan are likely falsified by the women who bring them forward. She said that in Jordan, women frequently use legal clauses related to rape for their own social or economic benefit. I was shocked. My first thought upon hearing this was, “There’s no f****ing way she just said that in the same breath as her previous statement about the lack of support that outspoken female survivors receive.” The professor then went on to tell a story about a female student of hers who sought her help 2 months after a widely-loved male professor at the graduate school sexually assaulted her. The professor told us about how she was suspicious as to why the student had waited so long to confront anyone, since the student “had a strong personality” and was therefore capable, in the professors eyes, of seeking immediate support. The professor then said that she discovered that the female student had recently received a bad grade from the male professor, and so she refused to take the student’s claims any further because she felt as though the student was simply trying to seek revenge for being given such a grade. When it finally came time to leave, I stepped out of the room feeling hollow and confused–I felt like I had less of a clear picture about the principles and values that the Centre stands and works for and about the overall condition of human rights in Jordan than before I had walked in.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

This narrative lies in stark contrast to the message and experience that my peers and I had at the Justice Center for Legal Aid, where our speaker was also a Jordanian woman who had received a law degree and frequently works on the front lines of women’s rights issues in civil court. When a few of us informed our Justice Center speaker about what the professor had told us at the Human Rights Centre, she said that the professor must have only worked a very small and isolated number of cases in order to come up with such an idea. Our Justice Center speaker told us that while abuse of rape legislation does sometimes occur, she put the frequency closer to 15% of the time rather than 95%. She expressed frustration that we had been given this false information, and encouraged us to think critically about why the professor might have believed that 95% was an accurate figure.

Visiting the Justice Center was also refreshing in other ways… It was amazing to be in a building staffed primarily by women (women with law degrees, no less!) who devote so much time and energy to making real, tangible change in the lives of marginalized people in Amman. The Justice Center focuses on offering legal aid and protection to women who are survivors of domestic abuse, small business owners, refugees and undocumented people living in Amman, senior citizens, and many more. We were given a tour of the main office, the legal clinic where beneficiaries have appointments with the Center’s pro-bono lawyers, the 24-hour hotline call center, and other office spaces involved with the reception, processing, and distribution of aid to the callers and inquirers who come to the Center seeking legal aid.

Our speaker informed us that the Justice Center is the only NGO/CSO in Jordan that provides pro-bono legal aid to everyone facing a 10+ year sentence within Jordan’s borders, regardless of documentation status. She explained to us that the Center focuses its legal aid efforts on the population of people in Jordan who would otherwise be barred from the legal process–the right to attorney does not exist in Jordan, and many people cannot afford to pay for this legal resource. A few of the legal issues that the Center frequently deals with involve the fact that women are not legally entitled to pass their citizenship onto their children, issues pertaining to providing divorces and financial and/or custodial justice for women who are survivors of domestic abuse, youth drug charges and other narcotics cases (youth as young as 12 can be tried as/detained alongside adults when it comes to drug cases), cases involving the neglect of the elderly, the cases of beneficiaries who have been convicted of “Cyber-Violence” for slandering other citizens or the King on social media, etc.

She also told us about the two 24-hour hotlines run by the Justice Center (one is for people who are currently under arrest or detention, and the other is for clients who need immediate physical and/or legal protection), and about the hotline staff who are responsible for providing immediate services and resources to individuals who may presently be in crisis. This job in particular sounded extremely emotionally and mentally demanding, and our speaker informed us that recently the Justice Center partnered with an external mental health provider to help ensure that the employees are able to process what they hear while working and better compartmentalize the secondhand trauma they may experience.

Overall, I felt as though the smaller, more focused Justice Center NGO was making a greater impact on the lives of individuals in the immediate community than the larger, government-funded National Centre for Human Rights. This is a pattern that I’ve been observing and grappling with since the start of our program in New York City, and while it’s really easy for me to jump to conclusions and make assumptions about the integrity of the organizations, I have to remember that they fundamentally serve different purposes because they operate at different levels of society–the gap between the federal and grassroots levels is yawning and full of various implications for the power of each to influence policy and act in the favor of marginalized people. What’s more, I also have to acknowledge that the folks at the Centre have what is essentially an impossible task–to hold the government and monarchy of Jordan accountable for protecting the human rights of its citizens while simultaneously existing under the harsh limitations of the government and monarchy in terms of free speech and what causes will/won’t be supported by the King. Not to mention, he’s where they get a huge chunk of their funding! After this week, I feel as though my brain is overflowing with new knowledge and new perspectives on the Jordanian legal system, and I am looking forward to discussing what I have learned with my academic allies back home to better understand where the American legal system stands and operates on the wide spectrum of legal systems around the world.

October 19, 2024 Comments Off on Week 1 in Jordan – Learning the Ropes of an Ancient City

Weeks 3-4 in Nepal – The Terai & “See you again”!

A small, lanky chicken scurried past my ankles as yet another droplet of sweat slipped past the edge of my eyebrow and fell into the silty dust beneath my feet. I glanced up and to my left as our host and educator for the day, Ranjana Lamsal, spoke with Parvati Mahato, the woman we had traveled by van over long, bumpy roads to visit. Parvati nodded and replied softly to Ranjana, gently bouncing her young, sleeping daughter in her arms as she spoke. I watched her multitask effortlessly–soothing her daughter as she recounted the story of her family’s dealings with a migration agent who ran away with over half of her family’s savings and forced her husband, Om, to start his foreign employment process from scratch for the second time in the span of a few months. Clearly, performing multiple forms of emotional labor at once was not a novelty for her.

When we arrived at her house, Parvati and her mother–a beautiful, wise-looking older woman with long silver hair and an analytical gaze–dragged as many plastic lawn chairs as they could find out of their house, along with one of the children’s beds, just so that we would have a place to sit for our meeting. I shifted uncomfortably on the bed’s hard, hand-carved wooden frame and taut nylon webbing, temporarily distracted by my mental image of how difficult it would be to sleep on the webbing’s rough knots every night.

The experience of visiting Parvati and hearing her story first-hand, sitting on one of her children’s beds in her yard in rural Nepal, is one that will stay with me for the rest of my life. While we were on our excursion to the Terai, a rural region in southern Nepal, my peers and I were able to visit the homes or neighborhoods of four individuals who had opened cases with the local government’s Migration Resource Center (MRC) to try to achieve justice for exploitation that themselves or their family members had faced/were facing as migrant laborers in Gulf Cooperation Council member-countries. The importance of sharing such personal settings with the individuals and families that we were lucky enough to listen to cannot be undermined–being physically present the places where they carried out their daily routines contextualized their stories and made the experience of learning from our speakers hyper-real for me.

Interacting with each individual we visited–all of them survivors of structural violence at the hands of the Nepali state, the government’s of GCC member-countries, and all the rich politicians in between–through normal conversations was also extremely effective for informing us about the day-to-day realities and consequences of undergoing struggles related to foreign employment within the Nepali/Eurasian/international system. It was because of the personal nature of those conversations that I began to understand what it looks and would feel like day-to-day for a single mom to raise her children without her husband, while he faces inhumane working conditions in Dubai, Qatar, etc. I was able to visualize the daily morning routine: preparing food, waking the children, getting them ready for school and/or work, feeding the animals, cleaning up the house, trying to get in touch with the relative abroad to check on them and receive information about how to advocate for them from thousands of miles away, and then making more phone calls or a long visit to the RMC to pass along information from the relative to case workers. If we hadn’t been sitting there in Parvati’s yard though, face-to-face with both the joy and struggles of her life, I don’t think I would have gained the same understanding.

Another thing that became abundantly clear to us through our site visits in the Kawasoti province of the Terai and beyond was the imperativeness of the Safer Migration (SaMi) program and the presence of the MRC in each district of Nepal. At one point during our site visits, Ranjana looked at each of us and said, “Now you see how important it is that we are here. If SaMi wasn’t here, who would advocate for justice for these families? It wouldn’t happen.” That concept stayed with me for the entire rest of the day and throughout the next as well, when we went to visit the local government office of Kawasoti. Our presentation experiences in the government buildings we visited in Terai were also highly informative, but they felt much staler than our interactions with the individuals and families that Ranjana introduced us to during our site visits.

Prior to those interactions, when we were listening to representatives of the MRC speak, I was more passively interested in what the speakers were talking about. The presentation took on a completely different meaning, however, when MRC clients began climbing the stairs and poking their heads into the room where we sat, asking for directions to one office or another to handle cases, inquire about services, look over documents, etc. The faces that appeared in the doorway were the reason that we were there- they were the manifestations of the knowledge and data being served to us on projected powerpoint slides, and it was only after I allowed myself to realize the weight of that connection that I became fully invested in what was going on around me.

Similarly, I don’t think I would have gotten nearly as much out of our visit to the Kawasoti municipality’s local government office had I not met Ranjana’s clients at their homes the day before. Honestly, the Kawasoti judicial committee presentation brought up a lot of anger and frustration for me, and I think I was feeling that way because I had fresh conversations with local people spinning around inside my head and providing personal, anecdotal context to the information we were being fed about Nepali policy and government structure. The Deputy Mayor explained the limitations of the power of local governments as that applies to bringing justice to labor migrants whose perpetrators flee to different provinces or countries, about her stance on divorce and the state’s involvement in domestic affairs, about the complexities of the civil vs. criminal case divide in terms of how the state can allocate resources to survivors, etc.

As she spoke, all I could think about was Parvati’s face as she held her daughter–the shadows under her eyes and the determination in the way she clenched her jaw. I thought of the young boy whose father committed suicide after returning from working abroad–I remembered the boy’s quiet resilience, how his life and mind have forever been altered by the struggles he inherited from his father during his early teenage years. How could the Deputy Mayor have such an honest, comprehensive understanding of the issues faced by this extremely vulnerable population in her community and seem to relay this information to us as if it was the most normal thing in the world? In the moment, I knew my anger was directed at the wrong person, the wrong place, but I couldn’t help but want to stand up and shout, “Yes! And do you have any idea how these policies are inflicting violence upon the people your government claims to represent and care for?”.

Once I had calmed down enough to think critically again, I eventually accepted that the Deputy Mayor must care deeply for her community to do the work she does, and that she and her colleagues are helping migrant workers in whatever ways they reasonably can–it’s the dynamics of the Nepali state that do not allow local governments to take much direct action, not individual negligence. I thought to myself, of course the Deputy Mayor and her colleagues can feel the pain of their community, and perhaps the frankness of her communication may just be an indicator of how long she has had to grapple with this kind of knowledge and how she has learned to cope with it.

It’s still frustrating that Nepali’s local governments are not able to do more to help prevent further harm in the future, but it’s thanks to women and workers like Ranjana that labor migrants at all stages can have some hope for justice and safety while abroad. Balancing the need for further progress with the ability to have gratitude for the social resources that already exist in rural Nepal is a tricky line to walk, and it’s a line I found myself walking every day in the Terai. My gratitude for being there and having the opportunity to learn from so many people with such different life stories is clear and undeniable, though–this experience has changed my worldview profoundly, and it is one that I’ll never forget.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

As I stepped through the dark wooden doorway, I wasn’t sure what to expect–Kat and I had been anxiously awaiting seeing this room of our homestay house for weeks, as it was one of the only rooms we hadn’t yet explored and we knew that it housed beautiful artwork. Nothing could have prepared me for the depth, detail, intricacy, and delicate beauty of the statues that arched and sat and danced and stomped before me, though. They looked so real, so divinely powerful, as if they might unfreeze and wield their mightiness upon us at any given second. Kat and I were mesmerized, so much so that we momentarily forgot that the quiet, humble man with endearing crow’s feet who padded quietly into the room behind us had created these figures with a few simple tools and deft skill of his calloused hands.

These were the kinds of moments that Kat and I found ourselves reflecting upon days later as we sat on yet another bougie Qatar Airways flight, sad to be leaving Nepal and excited for what lay ahead of us in Jordan. Before boarding, Yanik and his team had organized a lovely, tear-jerking final dinner with our homestay families. We all met at a cute cafe’s outdoor garden, and we exchanged gratitude and memories and more than a few glasses of wine underneath the twinkling party lights that were strung above us. Our host dad, Krishna, had a way of making Kat and I laugh that was totally unique–somehow, dad jokes are dad jokes anywhere in the world, and he definitely capitalized on his final opportunity to share them with us.

In our conversations about all that we had learned during our brief time in Nepal, I found myself thinking about how in a past life, I could have been like any of these wonderful people that I had met halfway around the world, and they could easily have been like me. It was a unifying thought–the comfort that we all share our humanity and the capacity to empathize with one another across our differences is profound.

I also found myself remembering our 22-hour bus ride back from Pokhara, a mountainous city full of beautiful cafes where gangsters launder their money and where ferryman spend their days paddling people across the city’s yawning lake.

My cohort ended up spending one more day than originally planned in Pokhara due to the devastating flooding that recently tore through the floodplains of Nepal and tore up the country’s roads, causing landslides and traffic and slowing down the provision of essential disaster-relief resources to affected areas. The flooding was severe–Nepal received half of it’s annual rainfall in two days, and despite the fact that government officials had been warned ahead of time of the impending storm, preventative measures were not taken to protect the lives and livelihoods of the populations most at risk. In recent years, working class communities (often comprised of daily-wage workers) have settled in haphazardly developed housing on the banks of the Bagmati River and its floodplains. This is the only place that many of these families can afford to live, and they suffered and lost the most at the hands of the recent flooding.

My cohort and I were extremely lucky, as were our host families in Patan, to have our lives and homes left intact in the wake of the floods. My peers and I did suffer, however, when we were confined inside our tourist bus for 22 hours on the trip back from Pokhara due to landslides, Indian drivers in massive, colorful trucks (colloquially known as “tippers”) asleep at the wheel with their engines cut off in the middle of the road, and a mass exodus of people trying to reach family members in need or on a journey to find refuge on higher ground. The journey was brutal- the day before, we had geared up for an eight-hour bus ride, but nothing could have prepared us for the claustrophobia, desperate humor, waves of helplessness, and ultimately, the strong group solidarity that we encountered while we were trapped on that bus.

Once again, Krishna set the absolute highest standard for the seriousness with which he took our collective safety and wellbeing as a member of our student support staff, but also as a true friend of us all. During many occasions in the wee hours of the morning, when we were stuck at absolute standstills due to the tipper drivers decisions to take naps in the middle of the road, Krishna got out of the bus and banged on the sides of the trucks to wake the drivers so that we could move forward. He would then lead us ON FOOT through a maze of moving/non-moving vehicles with haphazard headlights pointing this way and that until we had made it clear to the other side of the blockade. This process definitely put him in harms way, as many of the drivers were barely awake, but Krishna showed no fear- he was like Moses, parting the tipper-sea for us. When he was back on the bus, he made sure to check in with everyone and provided us with water to keep us hydrated, dark humor to keep us smiling and grounded, and hugs when we started to go a little cray. He is such an awesome human being, and many tears were shed when we were forced to say “see you again”. I can’t wait for my post-undergrad return to Kathmandu to reunite with him and my host family, and to send the Annapurna circuit as a team with him and Ellie and Sarah!

There were so many epic, bonding moments, so many life-changing conversations had between me and Krishna and Nirvana and Laboni and Yanik and my peers and our guest-lecturers and our host families, so many beautiful sunrises and evening walks back home from our beloved classroom space- It would take years to recount all that has happened in the last month to the degree that these experiences deserve, but alas, time marches on and so do I! As I sit here writing this from our hotel in Jordan, I must now begin to chronicle the incredibly different, equally fascinating and growth-inducing experience we have already begun to have here. In Nepal, they do not say goodbye- only see you again! Now we have said Salaam Alaikum to Jordan… more on this soon.

October 8, 2024 Comments Off on Weeks 3-4 in Nepal – The Terai & “See you again”!

Week 2 in Nepal – Sickness, the IOM, and Circus Kathmandu!

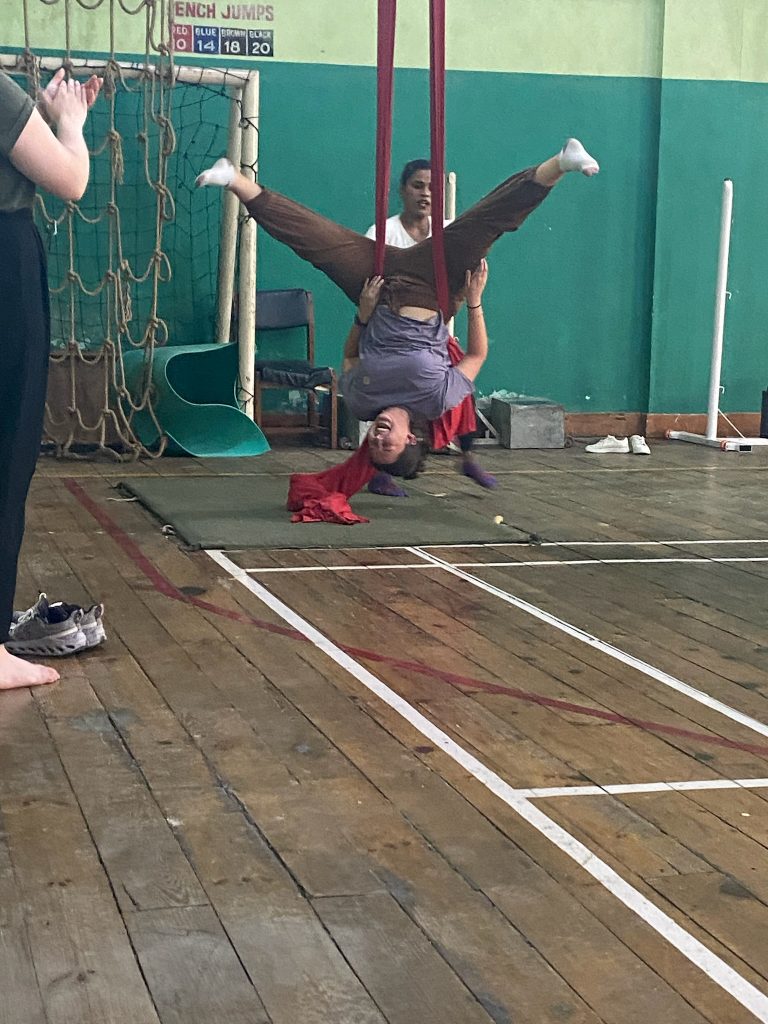

The first thing I noticed about the gym were the waxy, weathered floorboards… countless feet had run, jumped, spun, and danced here before mine. With each step, a subtle creak reminded us of the age of the space, the afternoons spent here that belong to strangers we would never know. The second thing I noticed was the heat- it hung like a shawl above us, reminding me that I need to stop expecting to be blasted by crisp AC wherever I go. We were ushered into the space by BJ L, the founder of Circus Kathmandu, and by two of it’s talented performers, Sheetal and Saraswati. My peers and I all found seats on benches that had been dragged into a semi-circle towards one side of the gym. and we eagerly awaited an introduction from our hosts.

BJ L welcomed us and quietly began to tell us his story. I had to lean in with my elbows on my knees to catch each of his softspoken words. He explained that he had grown up in a poor, rural community in Nepal in a family with multiple children. One day, when BJ L was eight, a man from India came to his village, singled out his parents, and promised them that if they sent BJ L with him, he would be able to provide English education, quality housing, and ample nutrition for their son- things that his parents were struggling to provide due to their economic circumstances. English education especially is an expensive and valuable commodity that is very hard to come by in poor communities. His parents agreed, and BJ L went with him and a few other children to India. Unfortunately, the reality that awaited them was a far cry from what had been promised. The man sold BJ L and the others to an Indian circus, and for four years that is all that BJ L knew. He became friends with a few of the other children that had been trafficked, and together they found the strength to endure the inhumane conditions they faced every day. Eventually, BJ L and the others were rescued by a humanitarian organization and he was returned home to his family. By then, he was a stranger to them- his parents did not recognize him at first, nor did he recognize them.

BJ L’s story is reflective of all of the stories of the staff and performers of Circus Kathmandu. Sheetal and Saraswati had also both survived human trafficking, and they listened quietly and looked at the floor while BJ L spoke. BJ L founded Circus Kathmandu in 2010 for the sake of showcasing beautiful human talent and dignity as well as to raise awareness and create social change around the issues of human trafficking and women’s health and equality in Nepal and around the world. Circus Kathmandu works with many local and international NGOs as advocates and workshop leaders,

BJ L then said, “But we are not here today just to focus on sad things. We may have sad stories, but today we are here to teach you and have fun.” And with that, music began playing and everyone rose and formed a circle. We each took turns running into the center of the circle and trying our best to choreograph a dance for everyone else to follow- it was HILARIOUS. The shift from sorrow to joy was so profound, so palpable- and it was all thanks to community, music, and dancing. We went on to play lots of other goofy games with BJ L and his team before they finally split us into groups to try to give us some circus skills. We were given crash courses on how to do circus tricks with hula hoops, how to juggle, and how to do some basic tricks on aerial silks- by far my favorite of the three activities. There is something about being suspended in mid-air with pointed toes and outstretched arms that makes you feel like you are flying! Our instructor Sheetal, who is a professional aerial artist, was very patient and gracious with us as we tried to replicate her strength and fluidity on the silks.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Unfortunately, another rousing event that took place this past week was a terrible bout of food poisoning for me. As I laid in bed after dinner on Sunday night, I got that gross, impending-doom feeling that something was very much wrong with my stomach. By the time that 5 am rolled around, I had puked eight times and probably slept an hour total. Luckily, our program coordinators Krishna, Laboni, and Nirvana were at the ready Monday morning to help get myself and a few other students to the clinic- over the course of the week, many of my peers started dropping like flies with various ailments, so the clinic trips became routine for our team.

The best part about being sick was the motorcycle ride. Technically, riding on motorcycles is a “forbidden activity” for SIT students… but dire times call for drastic measures (mwa ha ha!). After puking one more time for good measure, Krishna picked me up and plopped me down on the bike behind him. He lowered the rider foot pedals and instructed me NOT TO TAKE MY FEET OFF OF THEM. He was about to take off when, at the last moment, he stopped the bike and started rummaging through his bag. “Here,” he said. “Can’t forget this!” He winked and handed me a blue baseball cap. I immediately started laughing. “Is this my helmet?” I asked. He said, “Yup!” And with that we took off, tearing through the ancient streets of Patan. Other bikes, brightly-clothed pedestrians, moving carts piled high with irregular pieces of lumber or bright green vegetables blurred past as as Krishna expertly maneuvered through the dynamic chaos of the Patan alleys. The wind felt SO good on my face… I grinned wildly in the rearview mirror which made Krishna laugh. He shouted over the wind, “I’m going to have to convince Yanik that this wasn’t your master plan all along!”

When we pulled into the clinic, reality resumed too soon. The ride had made me dizzy, and the heat was oppressive. Luckily, Nirvana greeted us there with water and led us into the vast, air-conditioned lobby. The hospital was luxurious, and Nirvana warned us that while the doctors first priority was to help us get better, they were also motivated to make as much money off us as they could while doing so. “You do not have to stay the night if you don’t want to. Don’t let them make you think that you are on death’s door just so that you end up here for a few more hours!” For me, it wasn’t fear mongering that made me want to stay… it was the ridiculously comfortable beds and the cool, quiet room they took me to. After giving blood and taking some anti-nausea meds, I slipped into a merciful, heavenly sleep in my quiet corner. When the doctors awoke me and said that I would not need to be rehydrated with IV’s, I was at once relieved and disappointed. It was time to leave this strange paradise and go home. Nirvana called me a cab and I bumped and jostled my way back to my homestay, where my host dad and sister were waiting to help me get situated in my room. They were so, so kind to me, as they always are, and they made sure I had water and crackers and as much air circulation as possible in our small room. When I returned to school the next day, I credited the motorcycle ride as what had cured me.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

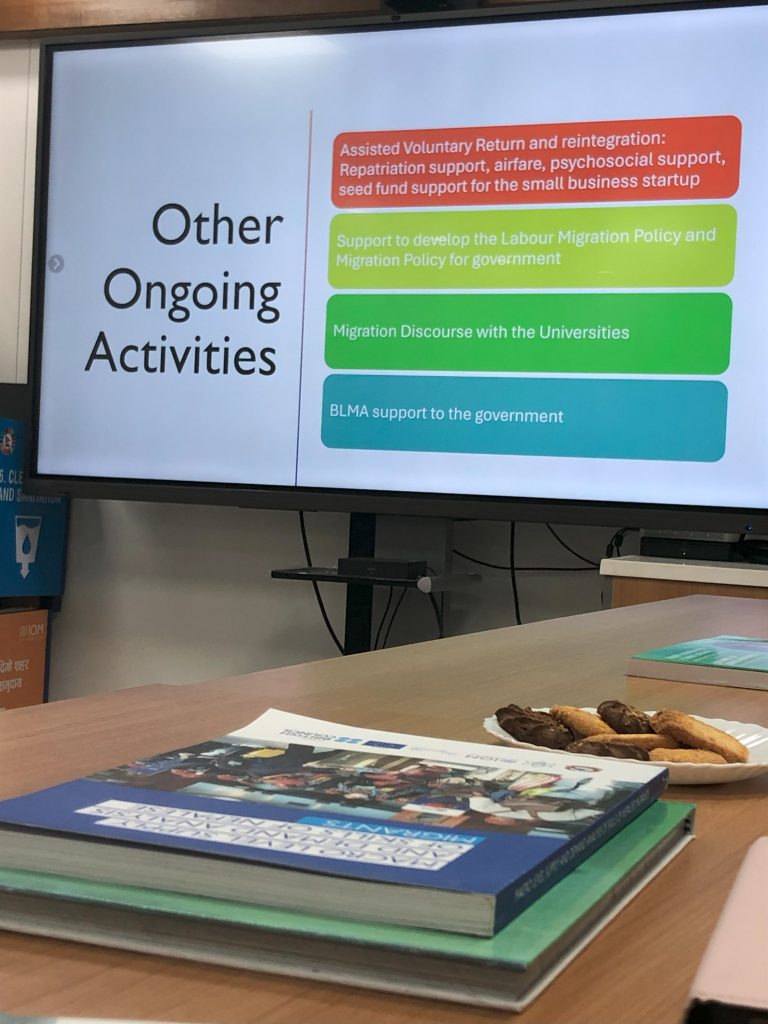

I have much, much work to catch up on after the few days that it took for me to regain my full energy and brainpower, so I will write about just one more place that our whole student group visited this week. Two days after my bout of sickness, my peers and I all piled into a van and went to visit the International Office of Migration in Nepal- a special branch of the U.N. that has an office in almost every country all over the world. The IOM is an INGO that “promotes humane and orderly migration for the benefit of all… by providing services and advice to migrants and governments.” Before we arrived, I had assumed that the IOM would focus on serving both migrants and refugees in terms of labor migration, resettlement, and with the intake and care of both vulnerable populations. But when we began listening to our speaker’s presentations, we were informed that IOM Nepal focuses solely on the process of moving people through Nepal, and on providing for the needs of migrants during that specific, transient period. Apparently refugees and asylum seekers are the responsibility of the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) in Nepal.

The first two floors of the IOM building smell like rubbing alcohol and look exactly like a hospital- performing health screenings and treating the medical conditions of migrants leaving Nepal are some of the IOM’s biggest priorities. The IOM works with nations in Europe, the U.S, Australia, New Zealand, and a few others to coordinate resettlement plans for documented Bhutanese, Middle-Eastern, Nepalese, etc. migrants that are in search of better lives. The key word here is documented- the status of being documented/undocumented makes all the difference in the kinds of resources that the IOM provides to migrants in Nepal. Documented migrants are given places to stay, basic healthcare, access to food pantries, and designated staff to help them plan their journeys and destinations. Undocumented migrants, however, are not legally eligible for IOM assistance, which creates a host of human rights issues for them. Based on our conversation, it was unclear as to whether the IOM or the UNHCR are able to provide any kind of direct aid to undocumented migrants, or whether this responsibility falls squarely on the shoulders of NGOs in Nepal. Either way, it seems problematic that such a large and vulnerable population of people in Nepal face such a dearth of resources and access to social services simply due to the status of their papers.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

This coming week, I will be traveling to the Terai region of Nepal! Specifically, our cohort will be going to Chitwan, a rural province of Nepal where rhinos roam and where tourism and development have created many environmental, social, cultural, and economic struggles and complexities. We will be speaking with two local NGOs in the community, one that serves and advocates for female survivors of domestic violence in the surrounding community (the problems created by the patriarchy and by gender-based-violence and power exist all over the world), and one that serves and advocates for foreign labor migrants and their families, who depend on the remittances that they send home. It will be such an honor and a privilege to see another side of life here in Nepal, and to have the opportunity to connect with members of a community that is so different from any other I have ever been a part of. I am very excited… stay tuned for more next week!

September 22, 2024 Comments Off on Week 2 in Nepal – Sickness, the IOM, and Circus Kathmandu!

Week 1 in Nepal!

The journey began with a bus and ended with a bus. All in all, we totaled ~22 hours of travel from JFK to KTM. Mercifully, our weariness was softened by the unexpected luxury we encountered on both of our Qatar flights- pillows, blankets, movie screens, and ample meals were all greedily consumed when offered. Still, most of us arrived at the Kathmandu airport feeling more dead than alive. There’s just no way to spend that long in transit without succumbing to the looming fatigue! My mood shifted as soon as we stepped out onto the tarmac, however, because I blinked and there they were… right before my eyes the Himalayas stood proudly, welcoming us to their homeland with an air of opulence that only the world’s grandest mountains can give off.

We were all introduced to Yanik, our new country coordinator, who was awaiting our arrival alongside his team – Krishna, Nirvana, and Laboni. They graciously took our luggage, threw it into a very cute and blessedly air-conditioned bus, and we started our hour-long commute to a hotel far up on a hillside overlooking the valley. The hotel acted as our transition space for two nights, before we were picked up by our homestay families.

The bus ride was slow but peaceful. It was mesmerizing to pass by so many houses and shops, occupied and run by people who live their lives in a place that used to exist only in my imagination. Motorcycles scittered behind and directly beside the bus like excited insects, their drivers unafraid to come within mere inches of the vehicles swirling around them. Many of the people we passed waved or nodded at the bus, which surprised me and painted a joyful expression across my face despite my fatigue. When we finally arrived at the hotel, we were provided with a Nepali-Western fusion style dinner to “ease our stomachs into Nepali food,” (Yanik is always looking out for us) and then it was off to our assigned rooms and our long-awaited beds. On the way down the path to my room, I was stopped in my tracks by the expansive view that stretched before me- off the hotel balcony, below the towering hill it was built on, the entire city of Kathmandu twinkled and shone, lit up by thousands of small, multicolored lights. The breadth of the city was astounding- I had no idea how big it would be. My friends and I sat and gazed in awe and laughed and shared our gratitude for being here with one another, and then we all fell into deep, much-needed sleeps.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Our first morning in Nepal was marked by further excitement, marvel, and gratitude. I crept quietly out onto the terrace first thing in the morning to call my boyfriend, and I could not believe how beautiful the valley was in both darkness and light. Great green mountains stretched in a powerful ring around the city, as if guarding it. Blue-gray pigeons hopped between the rooftops and chatted on wires, the noises of morning rituals began to rise from the houses around us, and prayers were loudly being broadcast from a nearby temple. The most dramatic of the views, however, was that of Ana Purna 2 (initially I misjudged it for Everest, lol) reaching up and scraping the sky from behind a softer, green range. There was a collective moment of exclamation as we all suddenly realized that the sharp white shape behind the other mountains was not, in fact, a cloud, but an epic mountain in its own right. I sat outside and stared at the mountain as long as I could- It’s knife’s-edge sharpness and towering height captivated me, topping off the list of epic mountains that I had seen this year (the Appalachian, the Sierra Nevada, and now the Himalaya?! PLEASE!).

Eventually, Krishna came down to wish us all good morning and to enjoy the view, too. He said that this was the first time in four years that Ana Purna 2 was visible from this hotel while SIT students were there- usually, the dust and the air pollution from the city, or bad weather, veiled the mountain’s full majesty. He explained that most of the Kathmandu valley was comprised of commercialized land, which is why we saw tiny houses perched high upon most of the hills around us. The hill our hotel was located on, however, was part of a national park and was thus protected by the Nepali government. Sure enough, we saw a long line of soldiers trudging up the street with big packs and big guns later that morning, conditioning themselves and checking in on things as per army requirements.

Our day in the classroom was filled with exciting and important orientation information relayed to us by Yanik and his team, E-SIM and SIM card distribution, and a fascinating lecture on the nation’s history and governmental goals, given to us by Anil- an environmental engineer who has been a part of numerous renewable energy initiatives in Nepal over the last 3 decades. I learned that Nepal’s gov’t has been transformed many times, but always from within- It was never colonized by outside forces, meaning that much of Nepal’s ancient historical sites and it’s indigenous cultural traditions have been better preserved than those of China or India. Additionally, Nepal’s current democratic republic has placed extreme value on two things: inclusion, and resilience. The current Nepali administration has set an honorable goal to include all members of society in society- one way they’ve made strides towards this goal is by including braille numbers on their coins, making Nepal the first country in the world to do so. That said, the rights of women and children are still extremely limited, which means that all Nepalis are still not equally included in society.

After our lecture, Krishna led interested parties on an “easy” hike up to the top of the hill/mountain our hotel was located on. We began walking straight up a very steeply graded, winding road and Krishna quickly asserted his place at the front of the pack. I was amazed by how fast he moved up such brutally steep terrain, and when I told him so, he laughed and said, “When I was training for the army, I had to run up this road! Walking is much easier.” I laughed too, deeply humbled. After about 10 minutes, we were all passed by Yanik on his motorcycle with Dr. Glaser at his back. She laughed and did a queenly wave as they flew by… faculty privileges, I suppose! When we finally reached the top, the rusted tower stood proudly, beckoning us to climb its many steel rungs. The view from the tower was beautiful- a soft breeze cooled our sweaty bodies as we watched the sun sink low and paint the many different mountain ranges with color. We spoke to a man on the tower who was a 75 year-old doctor (he looked maybe 55), who told us about the virtues of daily exercise and giving up gluten. I smiled, nodded, and dreamed of momos and soba pudding. Haha!

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

The remaining days flew by in a total blur of close calls with motorcycles, busy streets full of people and dogs, long but fascinating lectures, approximately 20 academic articles that demanded reading, the beginning and end of a research proposal, and lots of Dhal Bhat. We were formally introduced to Kathmandu by being thrust out into the entopic streets with our host mom, who mercifully walked us to school the first morning. I was AMAZED that we made it all the way there- and all the way back that afternoon- without witnessing multiple traffic-related fatalities. Motorcycles careened through the unbelievably narrow, winding maze of alleys in Patan, brushing by us with loud honks and mere inches to spare. Stray dogs napped in small patches of shade under parked cars, seemingly unbothered by the swarm of wheels whirring by and the cacophony of traffic noises. Faces appeared through the open storefronts along the street- men pounding metal, mannequins draped in rich magenta fabric teetering on the steps, women sorting bloody meat in butcher shops, children squinting and laughing among buckets and tables full of fruits and vegetables.

Starting the first morning that we spent in Nepal, my peers and I began receiving a host of lectures and presentations that served as a crash course in the Nepali government and it’s controversial agenda for rapid development across the nation, the economy, the nation’s history, the indigenous tribes in various regions, the prevailing realities of caste-based discrimination, and the major religions of Nepal (Buddhism, Hinduism, and many that blend in between). We had many notable presenters come into our classroom space who are involved with different facets of Nepali society- pre-law students from the Dalit community (Dalits are the community at the bottom of the caste system who have historically faced the most discrimination in Nepal, and continue to endure inhumane treatment today) who are determined to defend the rights of their friends and families, professors from local colleges, and many more.

We learned that there are 70+ political parties in Nepal, each of which fall into one or more of the following categories: Democratic, Communist, Socialist, Regressive, Identity, and/or Revolutionary. 6 parties from a variety of these categories come together to run the Nepali government under the president and prime minister (they have both!). Overall, around 60% of Nepalis support communist-based parties, but many of these parties are not truly communist in their practices. It’s very complicated and frankly I’m still fuzzy on a lot of this.

We also learned about the economic struggles and triumphs of the Nepali people. In rural areas, agriculture is the overwhelming source of income for most families- Dalits, however, face structural barriers to owning land, which means that it’s extremely hard to find work in rural areas (and in many urban ones, too). Hydroelectric power has become a huge industry in Nepal in the past few decades because of the abundant rainfall that Nepal receives during the monsoon season. Electricity is exported and sold to many of Nepal’s neighboring countries. This has been complicated by global warming and the disparate effects that climate change has had on Nepal in particular, though. Nowadays, the summers are hotter, the rainy season may be shorter or arrive later than normal, the majestic Himalayan peaks are coated with black soot and dust from the metropolitan areas in the valley, and both dust and smog smudge out the cities skies during long periods without rain. Seeing the haze in the air is very sad, and apparently the average Nepali loses three years of life simply by breathing in this air every day. In some areas of Nepal, people can lose up to five years. Climate justice is a huge issue here, and many people are fighting to make the government understand how dire the situation is- sound familiar?

We also took a class that focused on the different regionalities, traditions, and struggles that Nepal’s indigenous groups face. Many of our homestay families are from the Newar community- the indigenous community that were the original inhabitants of Kathmandu Valley. For the past week, my host mom has generously prepared lots of Newari cuisine for me to try, which has been delicious! Lots of earthy flavors from the frequent use of lentils and rice along with smoky and tangy flavors from the rainbow of spices she uses. My host sister Sonya is awesome- she is a journalist here in Patan, and she has been working for the Nepali times for eight years! She is smart as a whip and knows all about the complexities of politics, social norms, religion, and climate justice in Nepal. I love talking to her about the things I see on my walks to and from school, and about what we discuss in our lectures. When I came home one day after spending the afternoon learning about and discussing the caste system and the violence that it has created in Nepal (which is still very real- in 2020, a young boy from the Dalit community named Nabaraj BK and six of his close friends, also Dalits, were murdered and thrown into the Bheri river because Nabaraj had fallen in love with a girl from a higher caste. He and his friends were murdered while escorting Nabaraj to her house so that he could propose to her.), Sonya was able to help me process the intense emotions that I was feeling and informed me about her own experiences with caste in Nepal. Sonya made space for my sadness and allowed me to empathize with her, which helped me feel more grounded after such an intense day.